The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Haiti

This page contains a list of the greatest Haitian Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 49 of which were born in Haiti. This makes Haiti the birth place of the 68th most number of Politicians behind Algeria, and Chile.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Haitian Politicians of all time. This list of famous Haitian Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Haitian Politicians.

1. Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1758 - 1806)

With an HPI of 71.00, Jean-Jacques Dessalines is the most famous Haitian Politician. His biography has been translated into 54 different languages on wikipedia.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃ ʒak dɛsalin]; Haitian Creole: Jan-Jak Desalin; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was the first Haitian Emperor, leader of the Haitian Revolution, and the first ruler of an independent Haiti under the 1805 constitution. Initially regarded as governor-general, Dessalines was later named Emperor of Haiti as Jacques I (1804–1806) by generals of the Haitian Revolutionary army and ruled in that capacity until being assassinated in 1806. He spearheaded the resistance against French rule of Saint-Domingue, and eventually became the architect of the 1804 massacre of the remaining French residents of newly independent Haiti. Alongside Toussaint Louverture, he has been referred to as one of the fathers of the nation of Haiti. Under the rule of Dessalines, Haiti became the first country in the Americas to permanently abolish slavery. Dessalines served as an officer in the French army when Saint-Domingue was fending off Spanish and British incursions. Later he rose to become a commander in the revolt against France. As Toussaint Louverture's principal lieutenant, he led many successful engagements, including the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot. In 1802, Louverture was betrayed and captured, and sent to prison in France, where he died. Thereafter, Dessalines became the leader of the revolution and Général-Chef de l'Armée Indigène on 18 May 1803. His forces defeated the French army at the Battle of Vertières on 18 November 1803. Saint-Domingue was declared independent on 29 November and then as the independent Republic of Haiti on 1 January 1804, under the leadership of Dessalines, chosen by a council of generals to assume the office of governor-general. He ordered the 1804 Haitian massacre of the remaining French population in Haiti, killing between 3,000 and 5,000 people, and an exodus of thousands. Some historians cite the threat of a French reinvasion and reinstatement of slavery as one of the reasons for the massacre. Dessalines excluded surviving Polish Legionnaires, who had defected from the French, as well as Germans who did not take part in the slave trade. He granted them full citizenship and classified them as black. Tensions remained with the minority mixed-race population, who had gained some education and property during the colonial period. As Emperor, Dessalines enforced plantation labor to promote the economy and began an autocratic rule. In 1806, he was assassinated by members of his own administration and dismembered by a violent mob shortly thereafter. By the beginning of the 20th century, Dessalines began to be reassessed as an icon of Haitian nationalism. The national anthem of Haiti, "La Dessalinienne", written in 1903, is named in his honor.

2. Jean-Claude Duvalier (1951 - 2014)

With an HPI of 67.70, Jean-Claude Duvalier is the 2nd most famous Haitian Politician. His biography has been translated into 51 different languages.

Jean-Claude Duvalier (French: [ʒɑ̃klod dyvalje]; 3 July 1951 – 4 October 2014), nicknamed "Baby Doc" (Haitian Creole: Bebe Dòk, French: Bébé Doc), was a Haitian dictator who held the presidency of Haiti from 1971 until he was overthrown by a popular uprising in February 1986. He succeeded his father François "Papa Doc" Duvalier as the ruler of Haiti after his death in 1971. After assuming power, he introduced cosmetic changes to his father's regime and delegated much authority to his advisors. Thousands of Haitians were tortured and killed, and hundreds of thousands fled the country during his presidency. He maintained a notoriously lavish lifestyle (including a state-sponsored US$2 million wedding in 1980) while poverty among his people remained the most widespread of any country in the Western Hemisphere. Relations with the United States improved after Duvalier's ascension to the presidency, and later deteriorated under the Carter administration, only to normalize under Ronald Reagan due to the strong anti-communist stance of the Duvaliers. Rebellion against the Duvalier regime broke out in 1985, and Duvalier fled to France in 1986 on a U.S. Air Force flight. Duvalier unexpectedly returned to Haiti on 16 January 2011, after two decades in self-imposed exile in France. The following day, he was arrested by Haitian police, facing possible charges for embezzlement. On 18 January, Duvalier was charged with corruption. On 28 February 2013, Duvalier pleaded not guilty to charges of corruption and human rights abuse. He died of a heart attack on 4 October 2014, at the age of 63. Transparency International determined that the money embezzled by Duvalier was the sixth most embezzled by a sitting head of government between 1984 and 2004.

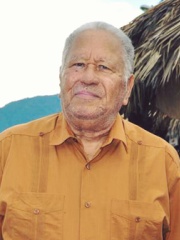

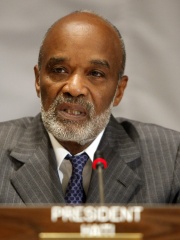

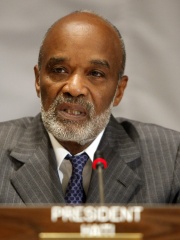

3. René Préval (1943 - 2017)

With an HPI of 66.56, René Préval is the 3rd most famous Haitian Politician. His biography has been translated into 49 different languages.

René Garcia Préval (French pronunciation: [ʁəne ɡaʁsja pʁeval]; 17 January 1943 – 3 March 2017) was a Haitian politician and agronomist who twice was President of Haiti, from early 1996 to early 2001, and again from mid-2006 to mid-2011. He was also Prime Minister from early to late 1991 under the presidency of Jean-Bertrand Aristide. In addition to being the first elected head of state since independence to serve a full term, the first to be elected to full terms of office without succeeding, the first to peacefully transfer power, and the first former prime minister to be elected president, Préval was also the first elected head of state in Haitian history to do so. Préval promoted privatization of government companies, agrarian reform, and investigations of human rights abuses. His presidencies were marked by domestic tumult and attempts at economic stabilization, with his latter term seeing the destruction brought by the 2010 Haiti earthquake.

4. Alexandre Pétion (1770 - 1818)

With an HPI of 65.77, Alexandre Pétion is the 4th most famous Haitian Politician. His biography has been translated into 28 different languages.

Alexandre Sabès Pétion (French pronunciation: [alɛksɑ̃dʁ sabɛs petjɔ̃]; 2 April 1770 – 29 March 1818) was a Haitian army officer and statesman who served as the first president of the Republic of Haiti from 1807 until his death in 1818. One of Haiti's founding fathers, Pétion belonged to the revolutionary quartet that also includes Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and his later rival Henri Christophe. Regarded as an excellent artilleryman in his early adulthood, Pétion would distinguish himself as an esteemed military commander with experience leading both French and Haitian troops. The 1802 coalition formed by him and Dessalines against French forces led by Charles Leclerc would prove to be a watershed moment in the decade-long conflict, eventually culminating in the decisive Haitian victory at the Battle of Vertières in 1803.

5. Jean-Pierre Boyer (1776 - 1850)

With an HPI of 64.91, Jean-Pierre Boyer is the 5th most famous Haitian Politician. His biography has been translated into 26 different languages.

Jean-Pierre Boyer (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃ pjɛʁ bwaje]; 15 February 1776 – 9 July 1850) was a Haitian military officer and statesman. He was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, and served as the president of Haiti from 1818 to 1843. He reunited the north and south of the country into the Republic of Haiti in 1820 and also annexed the newly independent Spanish Haiti (Santo Domingo), which brought all of Hispaniola under one Haitian government by 1822. Serving as president for just under 25 years, Boyer managed to rule for the longest period of time of any Haitian leader.

6. Jean-Bertrand Aristide (b. 1953)

With an HPI of 62.96, Jean-Bertrand Aristide is the 6th most famous Haitian Politician. His biography has been translated into 44 different languages.

Jean-Bertrand Aristide (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃ bɛʁtʁɑ̃ aʁistid]; born 15 July 1953) is a Haitian former Salesian priest and politician who served as president of Haiti in 1991, from 1993 to 1994, from 1994 to 1996, and from 2001 to 2004. He was in exile after the 1991 military coup until 1994 and again after his overthrow in 2004 until 2011. Aristide was a member of the Lavalas Political Organization before he founded the party Fanmi Lavalas in 1996. Aristide was appointed to a parish in Port-au-Prince in 1982 after completing his studies to become a priest of the Catholic Church. As a priest, he taught liberation theology and, as president, he attempted to normalize Afro-Creole culture, including Vodou religion, in Haiti. He became a focal point for the pro-democracy movement, first under Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier and then under the military transition regime which followed. Aristide won the December 1990 presidential election, which was seen as the first free and fair election in Haitian history, with 67% of the vote, but was ousted just months later in the September 1991 military coup. His first presidency began political reforms and introduced a moderate economic program. Aristide went into exile because of the coup, and after negotiations with the military regime did not resolve the crisis, U.S. pressure and threat of force in Operation Uphold Democracy caused its removal. During Aristide's return to power, he disbanded the Haitian military, which had a history of human rights abuses, and organized free elections during 1995. In 1996 he became the first elected Haitian leader to peacefully transfer power to an elected successor. He founded his own political party and returned to office after winning the November 2000 presidential election. In his economic policies, he tried to balance the interests of his populist supporters and foreign donors. He initially followed austerity policies that had been negotiated with the U.S., the World Bank, and the IMF, but he later increased the minimum wage in Haiti. His administration also built schools and hospitals, increased school enrollment, and established community stores to lower food costs. He faced increasing opposition during his second term, which coalesced as the Convergence Démocratique coalition, though he remained the most popular politician in Haiti. Aristide was ousted again in a February 2004 coup d'état after right-wing ex-army paramilitary members invaded the country from across the Dominican border. Aristide and many others have alleged that the United States had a role in orchestrating the second coup against him. In 2022, numerous Haitian and French officials told The New York Times that France and the United States had effectively overthrown Aristide by pressuring him to step down, though this was denied by James Foley, U.S. Ambassador to Haiti at the time of the coup. After the second coup against him, Aristide went into exile in the Central African Republic and South Africa. He returned to Haiti in 2011 after seven years in exile. Since his return he has focused on the work of his foundation and university. Aristide remains popular among Haitians, though there is controversy over violence by his supporters and allegations of his involvement in corruption.

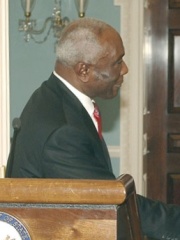

7. Ariel Henry (b. 1949)

With an HPI of 62.82, Ariel Henry is the 7th most famous Haitian Politician. His biography has been translated into 29 different languages.

Ariel Henry (French pronunciation: [aʁjɛl ɑ̃ʁi]; born 6 November 1949) is a Haitian neurosurgeon and politician who served as the acting prime minister of Haiti from the assassination of Jovenel Moïse in 2021 until his resignation in 2024, due to armed gangs taking over much of Port-au-Prince and being trapped outside of Haiti. During the period when the position of President of Haiti was vacant, executive authority was exercised by the Council of Ministers, which Henry presided over as acting prime minister. He also served as the acting Minister of Interior and Territorial Communities. Henry became mired in controversy due to his refusal to cooperate with the authorities regarding his connections with Joseph-Félix Badio, one of the suspects accused of orchestrating the assassination of Moïse. Officers who investigated the case suspected Henry was involved in planning the assassination. On 11 March 2024, Henry announced that he would resign when the Transitional Presidential Council was created, doing so on 24 April 2024 when the council was installed. Henry's outgoing cabinet appointed the Minister of Finance and Economy Michel Patrick Boisvert as the interim prime minister.

8. Anacaona (b. 1474)

With an HPI of 62.74, Anacaona is the 8th most famous Haitian Politician. Her biography has been translated into 21 different languages.

Anacaona (c. 1474 – c. 1504) was a Taíno cacica, zemi interpreter, composer, and poet born in Yaguana, Jaragua, Hispaniola (present-day Léogâne, Haiti). After the death of her brother Bohechío in 1500, she became the ruler of Jaragua. In the centuries since her death, she has been re-imagined and memorialized in various forms of poetry, music, and literature from the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and the wider Caribbean. Prior to becoming cacica, Anacaona was married to a Caonabo, a cacique from the Lucayos (now The Bahamas) who conquered the cacicazgo of Maguana in 1470. However, she spent most of her time in Jaragua with Bohechío. With Christopher Columbus's arrival in Hispaniola in 1492, the Spanish began enslaving Taínos, resulting in conflict. Caonabo, who fought against the Spanish, was ultimately captured and banished in 1496. After Christopher left, his brother Bartholomew took over the administration of Hispaniola in 1496. Anacaona played a prominent role during Bartholomew's visits to Jaragua, welcoming him, helping to facilitate tribute payments to him, and offering him valuable gifts, potentially suggesting her administrative authority and status as a steward of luxury goods. As cacica, Anacaona initially maintained a policy of cooperation with the Spanish, who continued to mistreat and enslave the Taíno. This led to frequent rebellions, with many enslaved Taíno fleeing to find sanctuary in Jaragua. In 1497, Spanish rebels led by Francisco Roldán also sought refuge in Jaragua among the Taíno. In 1502, Nicolás de Ovando arrived in Hispaniola after being appointed governor, and, after subduing the cacicazgo of Higüey, traveled to Jaragua in 1503. Anacaona welcomed him, gathering the local Taíno to honor him. However, after the Spanish massacre of between 40 and 80 caciques, for which various reasons have been proposed, she was captured and transported to Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic) and executed by the Spanish.

9. Leslie Manigat (1930 - 2014)

With an HPI of 62.49, Leslie Manigat is the 9th most famous Haitian Politician. His biography has been translated into 30 different languages.

Leslie François Saint Roc Manigat (French pronunciation: [lɛsli fʁɑ̃swa sɛ̃ ʁɔk maniɡa]; August 16, 1930 – June 27, 2014) was a Haitian politician who was elected as President of Haiti in a tightly controlled military held election in January 1988. He served as President for only a few months, from February 1988 to June 1988, before being ousted by the military in a coup d'état.

10. Faustin Soulouque (1782 - 1867)

With an HPI of 62.35, Faustin Soulouque is the 10th most famous Haitian Politician. His biography has been translated into 22 different languages.

Faustin-Élie Soulouque (French pronunciation: [fostɛ̃ eli suluk]; 15 August 1782 – 3 August 1867) was a Haitian politician and military officer who served as President of Haiti from 1847 to 1849 and Emperor of Haiti from 1849 to 1859. Soulouque was a general in the Haitian Army when he was appointed President of Haiti. He acquired autocratic powers, purged the army of the ruling elite, installed black loyalists in administrative positions and the nobility, and created a secret police and private army. Soulouque was an enthusiastic vodouisant, maintaining a staff of bokors and manbos, and gave the stigmatized vodou religion semi-official status which was openly practiced in Port-au-Prince. Soulouque declared the Second Empire of Haiti in 1849 after being proclaimed Emperor under the name Faustin I, and formally crowned in 1852. Several unsuccessful attempts to reconquer the Dominican Republic eroded his support and he abdicated in 1859 under pressure from General Fabre Geffrard. Soulouque was temporarily exiled to Jamaica before returning to Haiti where he died in 1867. Soulouque was the last Haitian head of state to have participated in the Haitian Revolution, the last to have been born prior to independence, the last ex-slave and the last to officially style himself as a king or emperor.

People

Pantheon has 49 people classified as Haitian politicians born between 1474 and 1980. Of these 49, 21 (42.86%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Haitian politicians include Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Ariel Henry, and Ertha Pascal-Trouillot. The most famous deceased Haitian politicians include Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Jean-Claude Duvalier, and René Préval. As of April 2024, 3 new Haitian politicians have been added to Pantheon including Alix Didier Fils-Aimé, Garry Conille, and Florence Duperval Guillaume.

Living Haitian Politicians

Go to all RankingsJean-Bertrand Aristide

1953 - Present

HPI: 62.96

Ariel Henry

1949 - Present

HPI: 62.82

Ertha Pascal-Trouillot

1943 - Present

HPI: 58.75

Michel Martelly

1961 - Present

HPI: 57.56

Michèle Pierre-Louis

1947 - Present

HPI: 57.00

Prosper Avril

1937 - Present

HPI: 55.66

Claudette Werleigh

1946 - Present

HPI: 55.65

Jean-Max Bellerive

1958 - Present

HPI: 54.22

Jacques-Édouard Alexis

1947 - Present

HPI: 53.88

Raoul Cédras

1949 - Present

HPI: 53.79

Jocelerme Privert

1953 - Present

HPI: 53.41

Joseph Jouthe

1961 - Present

HPI: 51.75

Deceased Haitian Politicians

Go to all RankingsJean-Jacques Dessalines

1758 - 1806

HPI: 71.00

Jean-Claude Duvalier

1951 - 2014

HPI: 67.70

René Préval

1943 - 2017

HPI: 66.56

Alexandre Pétion

1770 - 1818

HPI: 65.77

Jean-Pierre Boyer

1776 - 1850

HPI: 64.91

Anacaona

1474 - Present

HPI: 62.74

Leslie Manigat

1930 - 2014

HPI: 62.49

Faustin Soulouque

1782 - 1867

HPI: 62.35

Boniface Alexandre

1936 - 2023

HPI: 61.02

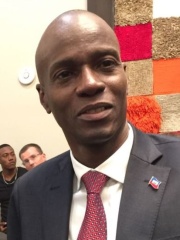

Jovenel Moïse

1968 - 2021

HPI: 60.69

Henri Namphy

1932 - 2018

HPI: 60.28

Vincent-Marie Viénot, Count of Vaublanc

1756 - 1845

HPI: 60.00

Newly Added Haitian Politicians (2025)

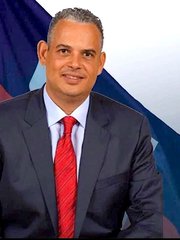

Go to all RankingsAlix Didier Fils-Aimé

1971 - Present

HPI: 50.42

Garry Conille

1966 - Present

HPI: 47.54

Florence Duperval Guillaume

1964 - Present

HPI: 44.29

Overlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 24 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.