The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Slovakia

This page contains a list of the greatest Slovak Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 72 of which were born in Slovakia. This makes Slovakia the birth place of the 46th most number of Politicians behind Lithuania, and Croatia.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Slovak Politicians of all time. This list of famous Slovak Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Slovak Politicians.

1. Alexander Dubček (1921 - 1992)

With an HPI of 80.13, Alexander Dubček is the most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 79 different languages on wikipedia.

Alexander Dubček (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈaleksander ˈduptʂek]; 27 November 1921 – 7 November 1992) was a Slovak statesman who served as the First Secretary of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) (de facto leader of Czechoslovakia) from January 1968 to April 1969 and as Chairman of the Federal Assembly from 1989 to 1992 following the Velvet Revolution. He oversaw significant reforms to the communist system during a period that became known as the Prague Spring, but his reforms were reversed and he was eventually sidelined following the Warsaw Pact invasion in August 1968. Best known by the slogan, "Socialism with a human face", Dubček led a process that accelerated cultural and economic liberalization in Czechoslovakia. Reforms were opposed by conservatives inside the party who benefited from the Stalinist economy, as well as interests in the neighbouring Soviet-bloc who feared contagion, western subversion, strategic vulnerability, and loss of institutional power. For reasons of institutional interests in the Soviet Union such as those of the military and KGB, false reports, and the growing concern among the Soviet leadership that Dubček was no longer able to maintain control of the country, Czechoslovakia was invaded by half a million Soviet-led Warsaw Pact troops on the night of 20–21 August 1968. This was intended to enable a coup by conservative forces. That coup, however, could not materialize due to lack of a viable pro-Soviet replacement leadership and the unexpected extraordinary popularity of Dubček and the reformist leadership. Soviet intervention ushered in a period of maneuver between conservatives and reformers where conservatives relied on Soviet influence to shift the balance of power, reversing reforms of the Prague Spring. Dubček was forced to resign as party head in April 1969, and was succeeded by Gustáv Husák, a former reformer and victim of Stalinism who was ambiguously favored by Moscow. This signaled the end of the Prague Spring and the beginning of normalization. Dubček was expelled from the Communist Party in 1970, amid a purge that eventually expelled almost two-thirds of the 1968 party membership. This mostly purged the younger generation of post-Stalin communists that he represented along with many of the most competent technical experts and managers. During the Velvet Revolution in 1989, Dubček served as the Chairman of the federal Czechoslovak parliament and contended for the presidency with Václav Havel. The European Parliament awarded Dubček the Sakharov Prize the same year. In the interim between the Prague Spring and the Velvet Revolution, Dubček withdrew from high politics but served as a leading inspiration and symbolic leader for Eurocommunism, maintaining intermittent contact with European communist reformers, especially in Italy and the Soviet Union. Also in 1989, just before his death, Andrei Sakharov wrote, "I am convinced that the 'breath of freedom' which the Czechs and the Slovaks enjoyed when Dubček was their leader was a prologue to the peaceful revolutions now taking place in eastern Europe and Czechoslovakia itself." Sakharov credited Dubček and the Prague Spring as his inspiration. At the time of his death in an automobile crash in 1992, Dubček remained an important political figure. Many saw him as the destined future president of newly-formed Slovakia.

2. Gyula Andrássy (1823 - 1890)

With an HPI of 75.56, Gyula Andrássy is the 2nd most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 42 different languages.

Count Gyula Andrássy de Csíkszentkirály et Krasznahorka (Hungarian: [ˈɒndraːʃi ˈɟulɒ], 8 March 1823 – 18 February 1890) was a Hungarian statesman, who served as Prime Minister of Hungary (1867–1871) and subsequently as Foreign Minister of Austria-Hungary (1871–1879). Andrássy was a conservative; his foreign policies looked to expanding the Empire into Southeast Europe, preferably with British and German support, and without alienating Turkey. He saw Russia as the main adversary, because of its own expansionist policies toward Slavic and Orthodox areas. He distrusted Slavic nationalist movements as a threat to his multi-ethnic empire.

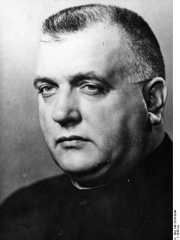

3. Jozef Tiso (1887 - 1947)

With an HPI of 75.55, Jozef Tiso is the 3rd most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 48 different languages.

Jozef Gašpar Tiso (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈjɔzef ˈtisɔ], Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈjoʒɛf ˈtiso]; 13 October 1887 – 18 April 1947) was a Slovak politician and Catholic priest who served as president of the First Slovak Republic, a client state of Nazi Germany during World War II, from 1939 to 1945. After the war, in 1947, he was convicted of treason and executed in Bratislava. Born in 1887 to Slovak parents in Nagybiccse (today Bytča), then part of Hungary, Austria-Hungary, Tiso studied several languages during his school career, including Hebrew and German. He was introduced to priesthood from an early age, and helped combat local poverty and alcoholism in what is now Slovakia. He joined the Slovak People's Party (Slovenská ľudová strana) in 1918 and became party leader in 1938 following the death of Andrej Hlinka. On 14 March 1939, the Slovak Assembly in Bratislava unanimously adopted Law 1/1939 transforming the autonomous Slovak Republic (that was until then part of Czechoslovakia) into an independent country. Two days after Nazi Germany seized the remainder of the Czech Lands, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was proclaimed. Jozef Tiso, who was already the prime minister of the autonomous Slovakia (under Czechoslovak laws), became the Slovak Republic's prime minister, and, in October 1939, he was elected its president. Tiso collaborated with Germany in deportations of Jews, deporting many Slovak Jews to extermination and concentration camps in Germany and German-occupied Poland, while some Jews in Slovakia were murdered outright. Deportations were executed from 25 March 1942 until 20 October 1942. An anti-fascist partisan insurgency was waged, culminating in the Slovak National Uprising in summer 1944, which was suppressed by German military authorities, with many of its leaders executed. Consequently, on 30 September 1944, deportations of Jews were renewed, with additional 13,500 deported. When the Soviet Red Army overran the last parts of western Slovakia in April 1945, Tiso fled to Austria and then Germany, where American troops arrested him and then had him extradited back to the restored Czechoslovakia, where he was convicted of high treason, betrayal of the national uprising and collaboration with the Nazis, and then executed by hanging in 1947 and buried in Bratislava. In 2008, his remains were buried in the canonical crypt of the Cathedral in Nitra, Slovakia.

4. Gustáv Husák (1913 - 1991)

With an HPI of 74.65, Gustáv Husák is the 4th most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 62 different languages.

Gustáv Husák (UK: HOO-sak, US: HOO-sahk, HEW-; Slovak: [ˈɡustaːw ˈɦusaːk]; 10 January 1913 – 18 November 1991) was a Czechoslovak politician who served as the long-time First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia from 1969 to 1987 and the President of Czechoslovakia from 1975 to 1989. Husák was born to an unemployed worker in Pozsonyhidegkút, Kingdom of Hungary, Austria-Hungary (now Bratislava-Dúbravka, Slovakia). He joined the Communist Youth Union at the age of sixteen while studying at the grammar school in Bratislava. In 1933, when he started his studies at the law faculty of the Comenius University in Bratislava, he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) which was banned from 1938 to 1945. During World War II, he was periodically jailed by the Jozef Tiso government for illegal Communist activities. He was one of the leaders of the 1944 Slovak National Uprising against Nazi Germany and Tiso. Husák was a member of the Presidium of the Slovak National Council from 1 to 5 September 1944. After the war, he began a career as a government official in Slovakia and party functionary in Czechoslovakia. From 1946 to 1950, he was the head of the devolved administration of Slovakia, and as such strongly contributed to the liquidation of the anti-communist Christian democratic Democratic Party of Slovakia. The Democratic Party of Slovakia established in 1944 had taken 62% in the 1946 elections in Slovakia (whereas in the Czech part of the republic of then-Czechoslovakia, the clear winners were the Communists), thus complicating the Communist ambitions for a swift taking of power. Husák's loyalty to the central organs of the Czechoslovak Communist party as well as his considerable talent for body politics and a ruthless approach to political opponents contributed largely to the crushing of the Democratic Party's dissent in Slovakia and releasing the popular opinion in the country to the whims of prevailing political currents. In 1950, he fell victim to a Stalinist purge of the party leadership, and was sentenced to life imprisonment, spending the years from 1954 to 1960 in the Leopoldov Prison. A convinced Communist, he always viewed his imprisonment as a gross misunderstanding, which he periodically stressed in several letters of appeal addressed to the party leadership. It is generally acknowledged that the then party leader and president Antonín Novotný repeatedly declined to pardon Husák, assuring his comrades that "you do not know what he is capable of if he comes to power". As part of the De-Stalinization period in Czechoslovakia, Husák's conviction was overturned and his party membership restored in 1963. By 1967, he had become a critic of Novotný and the KSČ's neo-Stalinist leadership. In April 1968, during the Prague Spring under new party leader and fellow Slovak Alexander Dubček, Husák became a vice-premier of Czechoslovakia, responsible for overseeing reforms in Slovakia.

5. Francis II Rákóczi (1676 - 1735)

With an HPI of 73.64, Francis II Rákóczi is the 5th most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 43 different languages.

Francis II Rákóczi (Hungarian: II. Rákóczi Ferenc, Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈraːkoːt͡si ˈfɛrɛnt͡s]; 27 March 1676 – 8 April 1735) was a Hungarian nobleman and leader of the Rákóczi's War of Independence against the Habsburgs in 1703–1711 as the prince (Hungarian: fejedelem) of the Estates Confederated for Liberty of the Kingdom of Hungary. He was also Prince of Transylvania, an Imperial Prince, and a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Today he is considered a national hero in Hungary. His name is historically also spelled Rákóczy, in Hungarian: II. Rákóczi Ferenc, in Slovak: František II. Rákoci, in German: Franz II. Rákóczi, in Croatian: Franjo II. Rákóczy (Rakoci, Rakoczy), in Romanian: Francisc Rákóczi al II-lea, in Serbian: Ференц II Ракоци. Although the Hungarian parliament offered Rákóczi the royal crown, he refused it, choosing instead the temporary title of the "Ruling Prince of Hungary". Rákóczi intended to bear this military-sounding title only during the anti-Habsburg war of independence. By refusing the royal crown, he proclaimed to Hungary that it was not his personal ambition that drove the war of liberation against the Habsburg dynasty.

6. Ferenc Szálasi (1897 - 1946)

With an HPI of 73.08, Ferenc Szálasi is the 6th most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 42 different languages.

Ferenc Szálasi (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈfɛrɛnt͡s ˈsaːlɒʃi]; 6 January 1897 – 12 March 1946) was a Hungarian military officer, politician, Nazi sympathizer and founder of the far-right Arrow Cross Party who headed the government of Hungary during the country's occupation by Nazi Germany in the final stages of World War II. Szálasi served with distinction during World War I as an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army. In 1925, he became a staff officer of the restored Kingdom of Hungary under Regent Miklós Horthy. Initially apolitical, Szálasi embraced right-wing ultranationalism in the early 1930s and became a passionate advocate of the irredentist Hungarism. In 1937, he founded the Hungarian National Socialist Party, having retired from the military and fully devoted himself to politics. He attracted considerable support through his virulently nationalist and antisemitic program, while his followers became increasingly radical, leading to his imprisonment in 1938. While in prison, he was proclaimed leader of the far-right Nazi Arrow Cross Party, which quickly became one of the most powerful political forces in the country. Szálasi was granted amnesty in 1940, but had to operate his party clandestinely after Horthy outlawed it on the outbreak of World War II. Following the German occupation of Hungary in March 1944 and Horthy's ousting in October, Szálasi was made head of government and head of state. His pro-Nazi puppet government, known as the Government of National Unity, was dominated by members of the Arrow Cross Party. The regime imposed martial law, participated in Germany's war efforts and recommenced the Holocaust in Hungary, which had been halted by Horthy. His militias were singularly responsible for the murder of 10,000–15,000 Hungarian Jews and for the deportation of a further 650,000 to death camps. Szálasi's collaborationist government, with its authority limited to the city of Budapest and its environs, only lasted 163 days. Facing the advance of Soviet and Romanian forces, Szálasi and his cabinet fled the country shortly before the Siege of Budapest began. He was captured by American troops in Austria in May 1945 and returned to Hungary to face trial. The Government of National Unity, which had relocated to Munich, was formally dissolved the next day. The People's Tribunal in Budapest found him guilty of war crimes and high treason, and sentenced him to death. He was executed by hanging on 12 March 1946.

7. Robert Fico (b. 1964)

With an HPI of 73.08, Robert Fico is the 7th most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 75 different languages.

Robert Fico (Slovak: [ˈrɔbert ˈfitsɔ]; born 15 September 1964) is a Slovak politician and lawyer who has served as the prime minister of Slovakia since 2023. Fico holds the distinction as the longest-serving prime minister in the country's history. His collective time in power spans over 12 years across four distinct mandates (2006–2010, 2012–2016, 2016–2018, and the current one since 2023). He founded the left-wing political party Direction – Social Democracy in 1999 and has led the party since. His political positions have been described as populist, left-wing and conservative. First elected to parliament in 1992, he was appointed the following year to the Czechoslovak delegation of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. Following his party's victory in the 2006 parliamentary election, he formed his first Cabinet, having secured 29.1% of the vote and 50 seats. After the 2010 parliamentary election, Fico served as an opposition member of parliament, effectively holding the position of the leader of the opposition, despite winning the most votes with 34.8% and securing 62 seats. Following a motion of no confidence against the Iveta Radičová cabinet, Fico was re-appointed prime minister after leading Direction – Social Democracy to a landslide election victory in the 2012 parliamentary election, winning 44.41% of the vote and 83 seats, forming a government with an absolute majority in Parliament, the first such since 1989. In 2013, Fico declared his candidacy for the 2014 presidential election, but ultimately lost to his political rival Andrej Kiska in the second round of voting. Fico began his third term as prime minister after Direction – Social Democracy won a plurality of the vote in the 2016 parliamentary election, securing 28.28% of the vote and 49 seats, subsequently forming a coalition government. In March 2018, owing to the political crisis following the murder of Ján Kuciak, Fico delivered his resignation to President Kiska, who then charged Deputy Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini with the formation of a new government. In the 2020 parliamentary election, his party finished second with 18.29% of the vote and 38 seats. Fico served in opposition from 2020 to 2023, a period marked by a significant split of his party, and a subsequent shift toward a populist platform. Following the 2023 parliamentary election, Fico's party emerged as the largest with 22.95% of the vote and 42 seats, which led to him forming his fourth Cabinet and returning as prime minister.

8. Béla I of Hungary (1016 - 1063)

With an HPI of 72.18, Béla I of Hungary is the 8th most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 41 different languages.

Béla I the Boxer or the Wisent (Hungarian: I. Bajnok or Bölény Béla, Slovak: Belo I.; c. 1015 – 11 September 1063) was King of Hungary from 1060 until his death. He descended from a younger branch of the Árpád dynasty. Béla's baptismal name was Adalbert. He left Hungary in 1031, together with his brothers, Levente and Andrew, after the execution of their father, Vazul. Béla settled in Poland and married Richeza (or Adelaide), daughter of Polish king Mieszko II Lambert. He returned to his homeland upon the invitation of his brother Andrew, who had in the meantime been crowned King of Hungary. Andrew assigned the administration of the so-called ducatus or "duchy", which encompassed around one-third of the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary, to Béla. The two brothers' relationship became tense when Andrew had his own son, Solomon, crowned king, and forced Béla to publicly confirm Solomon's right to the throne in 1057 or 1058. Béla, assisted by his Polish relatives, rebelled against his brother and dethroned him in 1060. He introduced monetary reform and subdued the last uprising aimed at the restoration of paganism in Hungary. Béla was fatally injured when his throne collapsed while he was sitting on it.

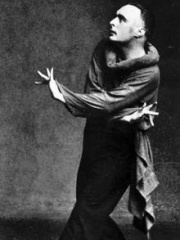

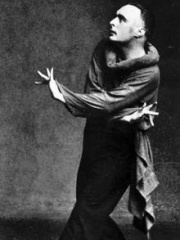

9. Rudolf von Laban (1879 - 1958)

With an HPI of 72.03, Rudolf von Laban is the 9th most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 43 different languages.

Rudolf (von) Laban, also known as Rudolph von Laban (Hungarian: Lábán Rudolf; 15 December 1879 – 1 July 1958), was an Austro-Hungarian dance artist, choreographer, and movement theorist. He is considered a "founding father of expressionist dance" and a pioneer of modern dance. His theoretical innovations included Laban movement analysis (a way of documenting human movement) and Labanotation (a movement notation system), which paved the way for further developments in dance notation and movement analysis. He initiated one of the main approaches to dance therapy. His work on theatrical movement has also been influential. He attempted to apply his ideas to several other fields, including architecture, education, industry, and management. Following a dress rehearsal of Laban's last choral work, Of the Warm Wind and New Joy, which he had prepared for the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Joseph Goebbels cancelled the piece after which time Laban fell out of favor with the National Socialist government. He eventually left Germany for England in 1937 after four years of working with the Nazi regime. Between 1945 and 1946, he and his long-term collaborator and former student Lisa Ullmann founded the Laban Art of Movement Guild in London, and the Art of Movement Studio in Manchester, where he worked until his death. The Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance in London has continued this legacy.

10. Ivan Gašparovič (b. 1941)

With an HPI of 71.80, Ivan Gašparovič is the 10th most famous Slovak Politician. His biography has been translated into 59 different languages.

Ivan Gašparovič (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈiʋaŋ ˈɡaʂparɔʋitʂ]; Croatian: Ivan Gašparović; born 27 March 1941) is a Slovak politician and lawyer who was the third president of Slovakia from 2004 to 2014. He was also the first and currently the only Slovak president to be re-elected.

People

Pantheon has 72 people classified as Slovak politicians born between 800 and 1993. Of these 72, 38 (52.78%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Slovak politicians include Robert Fico, Ivan Gašparovič, and Vladimír Mečiar. The most famous deceased Slovak politicians include Alexander Dubček, Gyula Andrássy, and Jozef Tiso. As of April 2024, 13 new Slovak politicians have been added to Pantheon including Ivan Korčok, Robert Kaliňák, and Michal Šimečka.

Living Slovak Politicians

Go to all RankingsRobert Fico

1964 - Present

HPI: 73.08

Ivan Gašparovič

1941 - Present

HPI: 71.80

Vladimír Mečiar

1942 - Present

HPI: 69.80

Andrej Babiš

1954 - Present

HPI: 67.53

Zuzana Čaputová

1973 - Present

HPI: 67.17

Rudolf Schuster

1934 - Present

HPI: 67.13

Andrej Kiska

1963 - Present

HPI: 65.70

Iveta Radičová

1956 - Present

HPI: 65.15

Peter Pellegrini

1975 - Present

HPI: 64.69

Mikuláš Dzurinda

1956 - Present

HPI: 63.48

Marián Čalfa

1946 - Present

HPI: 61.64

Miroslav Lajčák

1963 - Present

HPI: 60.41

Deceased Slovak Politicians

Go to all RankingsAlexander Dubček

1921 - 1992

HPI: 80.13

Gyula Andrássy

1823 - 1890

HPI: 75.56

Jozef Tiso

1887 - 1947

HPI: 75.55

Gustáv Husák

1913 - 1991

HPI: 74.65

Francis II Rákóczi

1676 - 1735

HPI: 73.64

Ferenc Szálasi

1897 - 1946

HPI: 73.08

Béla I of Hungary

1016 - 1063

HPI: 72.18

Rudolf von Laban

1879 - 1958

HPI: 72.03

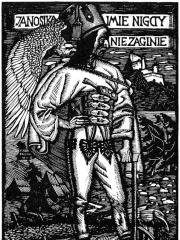

Juraj Jánošík

1688 - 1713

HPI: 71.26

Vojtech Tuka

1880 - 1946

HPI: 69.25

Milan Rastislav Štefánik

1880 - 1919

HPI: 68.64

Pribina

800 - 860

HPI: 68.06

Newly Added Slovak Politicians (2025)

Go to all RankingsIvan Korčok

1964 - Present

HPI: 52.01

Robert Kaliňák

1971 - Present

HPI: 48.11

Michal Šimečka

1984 - Present

HPI: 43.05

Mária Kolíková

1974 - Present

HPI: 39.79

Milan Jurčina

1983 - Present

HPI: 39.09

Richard Riszdorfer

1981 - Present

HPI: 38.62

Regina Pokorná

1982 - Present

HPI: 38.29

Tomáš Záborský

1987 - Present

HPI: 37.31

Marek Hrivík

1991 - Present

HPI: 36.55

Richard Pánik

1991 - Present

HPI: 36.36

Peter Čerešňák

1993 - Present

HPI: 34.20

Zuzana Števulová

1983 - Present

HPI: 34.10

Overlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.