The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from South Africa

This page contains a list of the greatest South African Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 65 of which were born in South Africa. This makes South Africa the birth place of the 54th most number of Politicians behind Thailand, and Pakistan.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary South African Politicians of all time. This list of famous South African Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of South African Politicians.

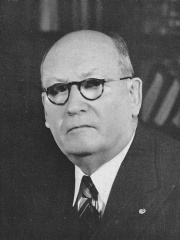

1. F. W. de Klerk (1936 - 2021)

With an HPI of 73.73, F. W. de Klerk is the most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 83 different languages on wikipedia.

Frederik Willem de Klerk ( də-KLURK, də-KLAIRK, Afrikaans: [ˈfriədərək ˈvələm də ˈklɛrk]; 18 March 1936 – 11 November 2021) was a South African politician who served as final state president of South Africa from 1989 to 1994 and as deputy president alongside Thabo Mbeki under President Nelson Mandela from 1994 to 1996. As South Africa's last head of state from the era of white-minority rule, he and his government dismantled the apartheid system and introduced universal suffrage. Ideologically a social conservative and an economic liberal, he led the National Party (NP) from 1989 to 1997. Born in Johannesburg to an influential Afrikaner family, de Klerk studied at Potchefstroom University before pursuing a career in law. Joining the NP, to which he had family ties, he was elected to parliament and sat in the white-minority government of P. W. Botha, holding a succession of ministerial posts. As a minister, he supported and enforced apartheid, a system of racial segregation that privileged white South Africans. After Botha resigned in 1989, de Klerk replaced him, first as leader of the NP and then as State President. Although observers expected him to continue Botha's defence of apartheid, de Klerk decided to end the policy. He was aware that growing ethnic animosity and violence was leading South Africa into a racial civil war. Amid this violence, the state security forces committed widespread human rights abuses and encouraged violence between the Xhosa and Zulu people, although de Klerk later denied sanctioning such actions. He permitted anti-apartheid marches to take place, legalised a range of previously banned anti-apartheid political parties, and freed imprisoned anti-apartheid activists such as Nelson Mandela. He also dismantled South Africa's nuclear weapons program. De Klerk negotiated with Mandela to fully dismantle apartheid and establish a transition to universal suffrage. In 1993, he publicly apologised for apartheid's harmful effects. He oversaw the 1994 non-racial election in which Mandela led the African National Congress (ANC) to victory; de Klerk's NP took second place. De Klerk then became Deputy President in Mandela's ANC-led coalition, the Government of National Unity. In this position, he supported the government's continued liberal economic policies but opposed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up to investigate past human rights abuses because he wanted total amnesty for political crimes. His working relationship with Mandela was strained, although he later spoke fondly of him. In May 1996, after the NP objected to the new constitution, de Klerk withdrew it from the coalition government; the party disbanded the following year and reformed as the New National Party. In 1997, he retired from active politics and thereafter lectured internationally. De Klerk was a controversial figure among many sections of South African society. He received many awards, including the Nobel Peace Prize (shared with Mandela) for his role in dismantling apartheid and bringing universal suffrage to South Africa. Conversely, he received criticism from anti-apartheid activists for offering only a qualified apology for apartheid, and for ignoring the human rights abuses by state security forces. He was also condemned by pro-apartheid Afrikaners, who contended that by abandoning apartheid, he betrayed the interests of the country's Afrikaner minority.

2. Shaka (1787 - 1828)

With an HPI of 73.31, Shaka is the 2nd most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 93 different languages.

Shaka kaSenzangakhona (c. 1787–24 September 1828), also known as Shaka (the) Zulu (Zulu pronunciation: [ˈʃaːɠa]) and Sigidi kaSenzangakhona, was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1816 to 1828. One of the most influential monarchs of the Zulu, he ordered wide-reaching reforms that reorganized the military into a formidable force. King Shaka was born in the lunar month of uNtulikazi (July) in 1787, in Mthonjaneni, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. The son of the Zulu King Senzangakhona kaJama, he was spurned as an illegitimate son. Shaka spent part of his childhood in his mother's settlements, where he was initiated into an ibutho lempi (fighting unit/regiment), serving as a warrior under Inkosi Dingiswayo. King Shaka refined the ibutho military system with the Mthethwa Paramountcy's support over the next several years. He forged alliances with his smaller neighbours to counter Ndwandwe raids from the north. The initial Zulu maneuvers were primarily defensive, as King Shaka preferred to apply pressure diplomatically, with an occasional strategic assassination. His reforms of local society built on existing structures. Although he preferred social and propagandistic political methods, he also engaged in several battles. King Shaka's reign coincided with the start of the Mfecane/Difaqane ("upheaval" or "crushing"), a period of devastating warfare and chaos in southern Africa between 1815 and 1840 that depopulated the region. His role in the Mfecane/Difaqane is controversial. He was assassinated by his half-brothers, King Dingane and Prince Mhlangana and Mbopha kaSithayi.

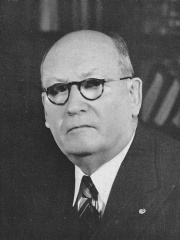

3. John Vorster (1915 - 1983)

With an HPI of 72.87, John Vorster is the 3rd most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 35 different languages.

Balthazar Johannes Vorster (Afrikaans pronunciation: [ˈbaltɑːzar juəˈhanəs ˈfɔrstər]; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983), better known as John Vorster, was a South African politician who served as the Prime Minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth State President of South Africa from 1978 to 1979. Known as B. J. Vorster during much of his career, he came to prefer the anglicized name John in the 1970s. He was interned in 1942 by the South African government for his involvement in the pro-Nazi Ossewabrandwag, but Vorster denied this and said the official reason given to him was for being “anti-British”. Vorster strongly adhered to his country's policy of apartheid, overseeing (as Minister of Justice) the Rivonia Trial, in which Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment for sabotage, (as Prime Minister) the Terrorism Act, the complete abolition of non-white political representation, the Soweto Riots and the Steve Biko crisis. He conducted a more pragmatic foreign policy than his predecessors, in an effort to improve relations between the white minority government and South Africa's neighbours, particularly after the break-up of the Portuguese colonial empire. Shortly after the 1978 Internal Settlement in Rhodesia, in which he was instrumental, he was implicated in the Muldergate Scandal. He resigned the premiership in favour of the ceremonial state presidency, from which he was forced out as well eight months later.

4. D. F. Malan (1874 - 1959)

With an HPI of 72.03, D. F. Malan is the 4th most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 32 different languages.

Daniël François Malan (Afrikaans pronunciation: [ˈdɑːni.əl franˈsʋɑː mɑːˈlan]; 22 May 1874 – 7 February 1959) was a South African politician who served as the fourth prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954. The National Party implemented the system of apartheid, which enforced racial segregation laws, during his tenure as prime minister.

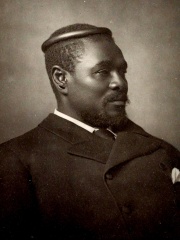

5. Cetshwayo kaMpande (1826 - 1884)

With an HPI of 71.14, Cetshwayo kaMpande is the 5th most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 29 different languages.

Cetshwayo kaMpande (; Zulu pronunciation: [ᵏǀétʃwajo kámpande]; c. 1826 – 8 February 1884) was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1873 to 1884 and its Commander in Chief during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. His name has been rendered as Cetywayo or Cetshwayo. Cetshwayo consistently opposed the war and sought fruitlessly to make peace with the British and was defeated and exiled following the Zulu defeat in the war. He was later allowed to return to Zululand, where he died in 1884.

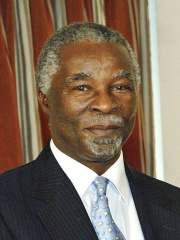

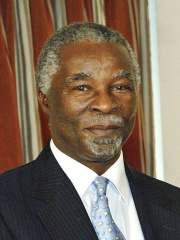

6. Thabo Mbeki (b. 1942)

With an HPI of 70.52, Thabo Mbeki is the 6th most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 94 different languages.

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki (Xhosa: [tʰaɓɔ ʼmbɛːki]; born 18 June 1942) is a South African politician and economist who served as the president of South Africa from 14 June 1999 to 24 September 2008, when he resigned at the request of his party, the African National Congress (ANC). Before that, he was deputy president under Nelson Mandela from 1994 to 1999. The son of Govan Mbeki, an ANC intellectual, Mbeki has been involved in ANC politics since 1956, when he joined the ANC Youth League, and has been a member of the party's National Executive Committee since 1975. Born in the Transkei, he left South Africa aged twenty to attend university in England, and spent almost three decades in exile abroad, until the ANC was unbanned in 1990. He rose through the organisation in its information and publicity section and as Oliver Tambo's protégé, but he was also an experienced diplomat, serving as the ANC's official representative in several of its African outposts. He was an early advocate for and leader of the diplomatic engagements which led to the negotiations to end apartheid. After South Africa's first democratic elections in 1994, he was appointed national deputy president. In subsequent years, it became apparent that he was Mandela's chosen successor, and he was elected unopposed as ANC president in 1997, enabling his rise to the presidency as the ANC's candidate in the 1999 elections. While deputy president, Mbeki had been regarded as a steward of the government's Growth, Employment and Redistribution policy, introduced in 1996, and as president he continued to subscribe to relatively conservative, market-friendly macroeconomic policies. During his presidency, South Africa experienced falling public debt, a narrowing budget deficit, and consistent, moderate economic growth. However, despite his retention of various social democratic programmes, and notable expansions to the black economic empowerment programme, critics often regarded Mbeki's economic policies as neoliberal, with insufficient consideration for developmental and redistributive objectives. On these grounds, Mbeki grew increasingly alienated from the left wing of the ANC, and from the leaders of the ANC's Tripartite Alliance partners, the Congress of South African Trade Unions and South African Communist Party. It was these leftist elements which supported Jacob Zuma over Mbeki in the political rivalry that erupted after Mbeki removed the latter from his post as deputy president in 2005. As president, Mbeki had an apparent predilection for foreign policy and particularly for multilateralism. His pan-Africanism and vision for an "African renaissance" are central parts of his political persona, and commentators suggest that he secured for South Africa a role in African and global politics that was disproportionate to the country's size and historical influence. He was the central architect of the New Partnership for Africa's Development and, as the inaugural chairperson of the African Union, spearheaded the introduction of the African Peer Review Mechanism. After the IBSA Dialogue Forum was launched in 2003, his government collaborated with India and Brazil to lobby for reforms at the United Nations, advocating for a stronger role for developing countries. Among South Africa's various peacekeeping commitments during his presidency, Mbeki was the primary mediator in the conflict between ZANU-PF and the Zimbabwean opposition in the 2000s. However, he was frequently criticised for his policy of "quiet diplomacy" in Zimbabwe, under which he refused to condemn Robert Mugabe's regime or institute sanctions against it. Also highly controversial worldwide was Mbeki's HIV/AIDS policy. His government did not introduce a national mother-to-child transmission prevention programme until 2002, when it was mandated by the Constitutional Court, nor did it make antiretroviral therapy available in the public healthcare system until late 2003. Subsequent studies have estimated that these delays caused hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths. Mbeki himself, like his Health Minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, has been described as an AIDS denialist, "dissident", or sceptic. Although he did not explicitly deny the causal link between HIV and AIDS, he often posited a need to investigate alternate causes of and alternative treatments for AIDS, frequently suggesting that immunodeficiency was the indirect result of poverty. His political descent began at the ANC's Polokwane conference in December 2007, when he was replaced as ANC president by Zuma. Although his term as national president was not due to expire until June 2009, he announced on 20 September 2008 that he would resign at the request of the ANC National Executive Committee. The ANC's decision to "recall" Mbeki was understood to be linked to a High Court judgement, handed down earlier that month, in which judge Chris Nicholson had alleged improper political interference in the National Prosecuting Authority and specifically in the corruption charges against Zuma. Nicholson's judgement was overturned by the Supreme Court of Appeal in January 2009, by which time Mbeki had been replaced as president by Kgalema Motlanthe.

7. C. R. Swart (1894 - 1982)

With an HPI of 70.52, C. R. Swart is the 7th most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 29 different languages.

Charles Robberts Swart (5 December 1894 – 16 July 1982), nicknamed "Blackie", was a South African politician who served as the last governor-general of the Union of South Africa from 1959 to 1961 and the first state president of the Republic of South Africa from 1961 to 1967.

8. Cyril Ramaphosa (b. 1952)

With an HPI of 70.27, Cyril Ramaphosa is the 8th most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 89 different languages.

Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa ( RAM-ə-FAW-sə or RAH-mə-POH-sə; (born 17 November 1952) is a South African businessman and politician serving as the president of South Africa since 2018. A former anti-apartheid activist and trade union leader, Ramaphosa is also the president of the African National Congress (ANC). Ramaphosa rose to national prominence as secretary general of South Africa's biggest and most powerful trade union, the National Union of Mineworkers. In 1991, he was elected ANC secretary general under ANC president Nelson Mandela and became the ANC's chief negotiator during the negotiations that ended apartheid. He was elected chairperson of the Constitutional Assembly after the country's first fully democratic elections in 1994 and some observers believed that he was Mandela's preferred successor. However, Ramaphosa resigned from politics in 1996 and became well known as a businessman, including as an owner of McDonald's South Africa, chair of the board for MTN, member of the board for Lonmin, and founder of the Shanduka Group. Ramaphosa returned to politics in December 2012 at the ANC's 53rd National Conference and served as the deputy president of South Africa under President Jacob Zuma from 2014 to 2018. He was also chairman of the National Planning Commission. At the ANC's 54th National Conference on 18 December 2017, he was elected president of the ANC. Two months later, the day after Zuma resigned on 14 February 2018, the National Assembly (NA) elected Ramaphosa as president of South Africa. He began his first full term as president in May 2019 following the ANC's victory in the 2019 general election. While president, Ramaphosa served as chairperson of the African Union from 2020 to 2021 and led South Africa's response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Ramaphosa's net worth was estimated at over R6.4 billion ($450 million) as of 2018. He has been criticised for his conduct and involvement in his business interests, including his harsh posture as a Lonmin director towards the Marikana miners' strike in the week ahead of the Marikana massacre. On 19 December 2022, it was announced that the ANC's 55th National Conference had elected Ramaphosa to a second term as president of the ANC. On 14 June 2024, the National Assembly of South Africa elected Ramaphosa to a second term as president of South Africa after the ANC lost its majority in the general election.

9. Jacob Zuma (b. 1942)

With an HPI of 70.06, Jacob Zuma is the 9th most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 93 different languages.

Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma (Zulu: [geɮʱejiɬeˈkisa ˈzʱuma]; born 12 April 1942) is a South African politician who served as the president of South Africa from 2009 to 2018. He is also referred to by his initials JZ and clan names Nxamalala and Msholozi. Zuma was a former anti-apartheid activist, member of uMkhonto weSizwe, and president of the African National Congress (ANC) from 2007 to 2017. He is also the father-in-law of Eswatini king, Mswati III, as of 2024. Zuma was born in the rural region of Nkandla, which is now part of the KwaZulu-Natal province and the centre of Zuma's support base. He joined the ANC at the age of 17 in 1959 and spent ten years in Robben Island Prison as a political prisoner. He went into exile in 1975 and was ultimately appointed head of the ANC's intelligence department. After the ANC was unbanned in 1990, he quickly rose through the party's national leadership and became deputy secretary general in 1991, national chairperson in 1994, and deputy president in 1997. He was the deputy president of South Africa from 1999 to 2005 under President Thabo Mbeki, Nelson Mandela's successor. Mbeki dismissed Zuma on 14 June 2005 after Zuma's financial adviser, Schabir Shaik, was convicted of making corrupt payments to Zuma in connection with the Arms Deal. Zuma was charged with corruption and was also acquitted on rape charges in the highly publicised 2006 trial. He managed to retain the support of a left-wing coalition inside the ANC, which allowed him to remove Mbeki as ANC president in December 2007 at the ANC's Polokwane elective conference. Zuma was elected president of South Africa in the 2009 general election and took office on 9 May. The criminal charges against him were formally withdrawn the same week. As president, he launched the R4-trillion National Infrastructure Plan and signed a controversial nuclear power deal with the Russian government, which was blocked by the Western Cape High Court in 2017. As a former member of the South African Communist Party, he increasingly relied on left-wing populist rhetoric, and in his 2017 State of the Nation address he announced a new policy of "radical economic transformation". Among the few policies implemented before the end of his presidency were land expropriation without compensation, free higher education, a series of attempted structural reforms in key sectors involving restrictions on foreign ownership, and more stringent black economic empowerment requirements. In the international arena, Zuma emphasised South-South cooperation and economic diplomacy. The admission of South Africa to the BRICS grouping has been described as a major triumph for Zuma, and he has been praised for his HIV/AIDS policy. Zuma's presidency was beset by controversy, especially during his second term. In 2014, the Public Protector found that Zuma had improperly benefited from state expenditure on upgrades to his Nkandla homestead, and in 2016, the Constitutional Court ruled that Zuma had failed to uphold the Constitution, leading to calls for his resignation and a failed impeachment attempt in the National Assembly. By early 2016, there were also widespread allegations, later investigated by the Zondo Commission, that the Gupta family had acquired immense corrupt influence over Zuma's administration, amounting to state capture. Several weeks after Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa was elected to succeed Zuma as ANC president in December 2017, the ANC National Executive Committee recalled Zuma. After a fifth vote of no confidence in Parliament, he resigned on 14 February 2018 and was replaced by Ramaphosa the next day. Shortly after his resignation, on 16 March 2018, the National Prosecuting Authority announced that it would reinstate corruption charges against Zuma in relation to the 1999 Arms Deal. He pleaded not guilty on 26 May 2021, but the trial was not scheduled to take place until early 2023. The trial has since been set for April 2025. In a separate matter, in June 2021, the Constitutional Court convicted Zuma of contempt of court for his failure to comply with a court order compelling his testimony before the Zondo Commission. He was sentenced to 15 months' imprisonment and was arrested on 7 July 2021 in Estcourt, KwaZulu-Natal. However, he was released on medical parole two months later on 5 September. The high court rescinded his parole on 15 December. The parole was declared unlawful by the Supreme Court of Appeal, but it allowed the Department of Correctional Services to consider whether to deduct the time spent under it from his sentence. On 11 August 2023, the Department of Correctional Services granted Zuma remission of his 15-month sentence.

10. J. G. Strijdom (1893 - 1958)

With an HPI of 69.55, J. G. Strijdom is the 10th most famous South African Politician. His biography has been translated into 27 different languages.

Johannes Gerhardus "Hans" Strijdom (14 July 1893 – 24 August 1958), nicknamed the Lion of the North and the Lion of Waterberg, was a South African politician who served as the fifth prime minister of South Africa from 1954 until his death in 1958. He was an uncompromising Afrikaner nationalist and a member of the white supremacist baasskap faction of the National Party (NP) who further accentuated the NP's apartheid policies and break with the Union of South Africa in favour of a republic during his rule.

People

Pantheon has 65 people classified as South African politicians born between 1787 and 1989. Of these 65, 19 (29.23%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living South African politicians include Thabo Mbeki, Cyril Ramaphosa, and Jacob Zuma. The most famous deceased South African politicians include F. W. de Klerk, Shaka, and John Vorster. As of April 2024, 2 new South African politicians have been added to Pantheon including David Mabuza, and Thando Hopa.

Living South African Politicians

Go to all RankingsThabo Mbeki

1942 - Present

HPI: 70.52

Cyril Ramaphosa

1952 - Present

HPI: 70.27

Jacob Zuma

1942 - Present

HPI: 70.06

Kgalema Motlanthe

1949 - Present

HPI: 65.25

Julius Malema

1981 - Present

HPI: 57.37

Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma

1949 - Present

HPI: 55.91

Grace Mugabe

1965 - Present

HPI: 52.22

Baleka Mbete

1949 - Present

HPI: 52.20

Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka

1955 - Present

HPI: 51.46

Helen Zille

1951 - Present

HPI: 51.04

Naledi Pandor

1953 - Present

HPI: 46.82

Patricia de Lille

1951 - Present

HPI: 45.73

Deceased South African Politicians

Go to all RankingsF. W. de Klerk

1936 - 2021

HPI: 73.73

Shaka

1787 - 1828

HPI: 73.31

John Vorster

1915 - 1983

HPI: 72.87

D. F. Malan

1874 - 1959

HPI: 72.03

Cetshwayo kaMpande

1826 - 1884

HPI: 71.14

C. R. Swart

1894 - 1982

HPI: 70.52

J. G. Strijdom

1893 - 1958

HPI: 69.55

Dingane kaSenzangakhona

1795 - 1840

HPI: 68.68

Paul Kruger

1825 - 1904

HPI: 68.61

P. W. Botha

1916 - 2006

HPI: 67.80

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela

1936 - 2018

HPI: 67.16

Mpande kaSenzangakhona

1798 - 1872

HPI: 65.98

Newly Added South African Politicians (2025)

Go to all RankingsOverlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.