The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Libya

This page contains a list of the greatest Libyan Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 47 of which were born in Libya. This makes Libya the birth place of the 71st most number of Politicians behind Kazakhstan, and Philippines.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Libyan Politicians of all time. This list of famous Libyan Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Libyan Politicians.

1. Muammar Gaddafi (1942 - 2011)

With an HPI of 85.50, Muammar Gaddafi is the most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 142 different languages on wikipedia.

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi (c. 1942 – 20 October 2011) was a Libyan military officer, revolutionary, politician, and political theorist who ruled Libya from 1969 until his overthrow by Libyan rebel forces in 2011 during the First Libyan Civil War. He came to power through a military coup, first becoming Revolutionary Chairman of the Libyan Arab Republic from 1969 to 1977, Secretary General of the General People's Congress from 1977 to 1979, and then the Brotherly Leader of the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya from 1979 to 2011. Initially ideologically committed to Arab nationalism and Arab socialism, Gaddafi later ruled according to his own Third International Theory. Born near Sirte, Italian Libya, to a poor Bedouin Arab family, Gaddafi became an Arab nationalist while at school in Sabha, later enrolling in the Royal Military Academy, Benghazi. He founded a revolutionary group known as the Free Officers movement which deposed the Western-backed Senussi monarchy of Idris in a 1969 coup. Gaddafi converted Libya into a republic governed by his Revolutionary Command Council. Ruling by decree, he deported Libya's Italian population and ejected its Western military bases. He strengthened ties to Arab nationalist governments and unsuccessfully advocated pan-Arab political union. An Islamic modernist, he introduced sharia law as the basis for the legal system and promoted Islamic socialism. He nationalized the oil industry and used the increasing state revenues to bolster the military, fund foreign revolutionaries, and implement social programs emphasizing housebuilding, healthcare and education projects. In 1973, he initiated a "Popular Revolution" with the formation of Basic People's Congresses, presented as a system of direct democracy, but retained personal control over major decisions. He outlined his Third International Theory that year in The Green Book. In 1977, Gaddafi transformed Libya into a new socialist state called a Jamahiriya ("state of the masses"). He officially adopted a symbolic role in governance but remained head of both the military and the Revolutionary Committees responsible for policing and suppressing dissent. During the 1970s and 1980s, Libya's unsuccessful border conflicts with Egypt and Chad, support for foreign militants, and alleged responsibility for bombings of Pan Am Flight 103 and UTA Flight 772 left it increasingly isolated on the world stage. A particularly hostile relationship developed with Israel, the United States and the United Kingdom, resulting in the 1986 U.S. bombing of Libya and United Nations–imposed economic sanctions. From 1999, Gaddafi shunned pan-Arabism, and encouraged pan-Africanism and rapprochement with Western nations; he was Chairperson of the African Union from 2009 to 2010. Amid the 2011 Arab Spring, protests against widespread corruption and unemployment broke out in eastern Libya. The situation descended into civil war, in which NATO intervened militarily on the side of the anti-Gaddafist National Transitional Council (NTC). Gaddafi's government was overthrown; he retreated to Sirte only to be captured, tortured and killed by NTC militants. A highly divisive figure, Gaddafi dominated Libya's politics for four decades and was the subject of a pervasive cult of personality. He was decorated with various awards and praised for his anti-imperialist stance, support for Arab—and then African—unity, as well as for significant development to the country after the discovery of oil reserves. Conversely, many Libyans strongly opposed Gaddafi's social and economic reforms; he was accused of various human rights violations. He was condemned by many as a dictator whose authoritarian administration systematically violated human rights and financed terrorism in the region and abroad.

2. Septimius Severus (145 - 211)

With an HPI of 82.04, Septimius Severus is the 2nd most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 85 different languages.

Lucius Septimius Severus (; Latin: [ˈɫuːkiʊs sɛpˈtɪmiʊs sɛˈweːrʊs]; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna, Libya in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary succession of offices under the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus. Severus was the final contender to seize power after the death of the emperor Pertinax in 193 during the Year of the Five Emperors. After deposing and killing the incumbent emperor Didius Julianus, Severus fought his rival claimants, the Roman generals Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus. Niger was defeated in 194 at the Battle of Issus in Cilicia. Later that year Severus waged a short punitive campaign beyond the eastern frontier, annexing the Kingdom of Osroene as a new province. Severus defeated Albinus three years later at the Battle of Lugdunum in Gaul. Following the consolidation of his rule over the western provinces, Severus waged another brief, more successful war in the east against the Parthian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 197 and expanding the eastern frontier to the Tigris. He then enlarged and fortified the Limes Arabicus in Arabia Petraea. In 202, he campaigned in Africa and Mauretania against the Garamantes, capturing their capital Garama, and expanding the Limes Tripolitanus along the southern desert frontier of the empire. With his second wife, Julia Domna, Severus had two sons; the elder, Caracalla, was proclaimed Augustus, or co-emperor, in 198, and the younger, Geta, in 209. Severus travelled to Britain in 208, strengthening Hadrian's Wall and reoccupying the Antonine Wall. In 209, he invaded Caledonia (modern Scotland) with an army of 50,000 men but his ambitions were cut short when he died of an infectious disease in early 211 at Eboracum (modern York). His sons, advised by Julia Domna, succeeded him, thus founding the Severan dynasty. It was the last dynasty of the Roman Empire before the Crisis of the Third Century.

3. Simon of Cyrene (100 BC - 100)

With an HPI of 76.33, Simon of Cyrene is the 3rd most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 41 different languages.

Simon of Cyrene (Hebrew: שמעון, Standard Hebrew Šimʿon, Tiberian Hebrew Šimʿôn; Greek: Σίμων Κυρηναῖος, Simōn Kyrēnaios) was the man compelled by the Romans to carry the cross of Jesus of Nazareth as Jesus was taken to his crucifixion, according to all three Synoptic Gospels: He was also the father of the disciples Rufus and Alexander.

4. Idris of Libya (1889 - 1983)

With an HPI of 73.19, Idris of Libya is the 4th most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 54 different languages.

Idris (Arabic: إدريس, romanized: Idrīs, Muhammad Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Sanusi; 13 March 1890 – 25 May 1983) was King of Libya from 24 December 1951 until his ousting in the 1 September 1969 coup d'état. He ruled over the United Kingdom of Libya from 1951 to 1963, after which the country became known as simply the Kingdom of Libya. Idris had served as Emir of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania from the 1920s until 1951. He also headed the Sanusi order. Idris was born into the Senussi Order. When his cousin Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi abdicated as leader of the Order, Idris took his position. The Senussi campaign was taking place, with the British and Italians fighting the Order. Idris put an end to the hostilities and, through the Modus vivendi of Acroma, abandoned Ottoman protection. Between 1919 and 1920, Italy recognized Senussi control over most of Cyrenaica in exchange for the recognition of Italian sovereignty by Idris. Idris then led his Order in an unsuccessful attempt to conquer the eastern part of the Tripolitanian Republic. Following the Second World War, the United Nations General Assembly called for Libya to be granted independence. It established the United Kingdom of Libya through the unification of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan, appointing Idris to rule it as king. Wielding significant political influence in the impoverished country, Idris banned political parties and, in 1963, replaced Libya's federal system with a unitary state. He established links to the Western powers, allowing the United Kingdom and United States to open military bases in the country in return for economic aid. After oil was discovered in Libya in 1959, he oversaw the emergence of a growing oil industry that rapidly aided economic growth. Idris's regime was weakened by growing Arab nationalist and Arab socialist sentiment in Libya as well as rising frustration at the country's high levels of corruption and close links with Western nations. While in Turkey for medical treatment, Idris was deposed in a 1969 coup d'état by army officers led by Muammar Gaddafi.

5. Mustafa Abdul Jalil (b. 1952)

With an HPI of 68.78, Mustafa Abdul Jalil is the 5th most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 33 different languages.

Mustafa Abdul Jalil (Arabic: مصطفى عبد الجليل; also transcribed Abdul-Jelil, Abd-al-Jalil, Abdel-Jalil, Abdeljalil or Abdu Al Jeleil; born 6 November 1952) is a Libyan politician who was the Chairman of the National Transitional Council from 5 March 2011 until its dissolution on 8 August 2012. This position meant he was de facto head of state during a transitional period after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi's government in the Libyan Civil War, and until the handover of power to the General National Congress. Before the war, Abdul Jalil served as Muammar Gaddafi's Minister of Justice (officially, the Secretary of the General People's Committee of Justice). He was noted in some news media for his stance against various human rights violations in Libya, although Diana West accused him of intransigence during the Bulgarian nurses affair.

6. Aguila Saleh Issa (b. 1944)

With an HPI of 65.96, Aguila Saleh Issa is the 6th most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 18 different languages.

Aguila Saleh Issa Gueider (Arabic: عقيلة صالح عيسى اقويدر; born January 11, 1944) is a Libyan jurist and politician who is the Speaker of the Libyan House of Representatives since 2014. He therefore served as the head of state of Libya from 2014 to 2021 under the Tobruk-based second Cabinet of Prime Minister Abdullah al-Theni, which, from its formation in 2014 to the formation of the Tripoli-based Cabinet of Fayez al-Sarraj in 2016, was recognized by the international community as the legitimate government of Libya during the second Libyan civil war. He is also a representative of the town of Al Qubbah, in the east of the country.

7. Mahmoud Jibril (1952 - 2020)

With an HPI of 65.66, Mahmoud Jibril is the 7th most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 34 different languages.

Mahmoud Jibril el-Warfally (Arabic: محمود جبريل الورفلي), also transcribed Jabril or Jebril or Gebril (28 May 1952 – 5 April 2020), was a Libyan politician who served as the interim Prime Minister of Libya for seven and a half months during the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi and the Libyan Civil War, chairing the executive board of the National Transitional Council (NTC) from 5 March to 23 October 2011. He also served as the Head of International Affairs. As of July 2012, Jibril was the head of one of the largest political parties in Libya, the National Forces Alliance. Toward the end of the conflict, Jibril was increasingly referred to by foreign governments and in media as the interim prime minister of Libya. Jibril's government was recognized as the "sole legitimate representative" of Libya by the majority of UN states including France, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, Iran, and Qatar.

8. Fayez al-Sarraj (b. 1960)

With an HPI of 64.89, Fayez al-Sarraj is the 8th most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 48 different languages.

Fayez Mustafa al-Sarraj (Arabic: فائز السراج or فايز السراج; born 20 February 1960) is a Libyan politician who served as the Chairman of the Presidential Council of Libya and head of government of the Government of National Accord, which was formed on 17 December 2015 under the Libyan Political Agreement, from 2016 to 2021. He has been a member of the Parliament of Tripoli.

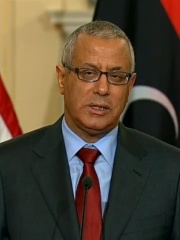

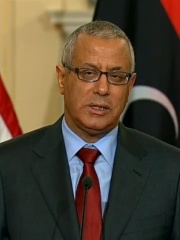

9. Ali Zeidan (b. 1950)

With an HPI of 63.50, Ali Zeidan is the 9th most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 29 different languages.

Ali Zeidan (sometimes written as Zidan; Arabic: علي زيدان; born 5 December 1950) is a former prime minister of Libya. He was appointed by the General National Congress on 14 October 2012, and took office on 14 November after Congress approved his cabinet nominees. Prior to the Libyan Civil War, Zeidan was a Geneva-based human rights lawyer. According to the BBC, he is considered by some local observers as a strong-minded liberal. He was ousted by the parliament committee and fled from Libya on 14 March 2014. However, he told a press conference in Rabat, Morocco, that the ousting was invalid.

10. Baghdadi Mahmudi (b. 1945)

With an HPI of 63.43, Baghdadi Mahmudi is the 10th most famous Libyan Politician. His biography has been translated into 27 different languages.

Baghdadi Ali Mahmudi (Arabic: البغدادي علي المحمودي; born 1945) is a Libyan politician who was Secretary of the General People's Committee (prime minister) of Libya from 5 March 2006 to as late as 1 September 2011, when he acknowledged the collapse of the GPCO and the ascendance of the National Transitional Council as a result of the Libyan Civil War. He has a medical degree, specialising in obstetrics and gynecology, and had served as Deputy Prime Minister to Prime Minister Shukri Ghanem since 2003 at the time he was appointed to replace him. He was a part of Gaddafi's inner circle at least prior to his escape in mid-2011. He was arrested in Tunisia for illegal border entry and jailed for six months, although this was later overruled on appeal, however a Tunisian court decided to extradite Mahmoudi to Libya under a request from Libya's Transitional Council. Mahmudi was released from prison on 20 July 2019.

People

Pantheon has 47 people classified as Libyan politicians born between 900 BC and 2000. Of these 47, 24 (51.06%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Libyan politicians include Mustafa Abdul Jalil, Aguila Saleh Issa, and Fayez al-Sarraj. The most famous deceased Libyan politicians include Muammar Gaddafi, Septimius Severus, and Simon of Cyrene. As of April 2024, 3 new Libyan politicians have been added to Pantheon including Fathi Bashagha, Ahmed Maiteeq, and Moussa Ibrahim.

Living Libyan Politicians

Go to all RankingsMustafa Abdul Jalil

1952 - Present

HPI: 68.78

Aguila Saleh Issa

1944 - Present

HPI: 65.96

Fayez al-Sarraj

1960 - Present

HPI: 64.89

Ali Zeidan

1950 - Present

HPI: 63.50

Baghdadi Mahmudi

1945 - Present

HPI: 63.43

Mohammed Magariaf

1940 - Present

HPI: 62.37

Saif al-Islam Gaddafi

1972 - Present

HPI: 62.04

Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh

1958 - Present

HPI: 60.93

Abdullah Senussi

1949 - Present

HPI: 59.66

Abdullah al-Thani

1954 - Present

HPI: 58.88

Mohamed Abu al-Qasim al-Zwai

1952 - Present

HPI: 58.74

Mohamed al-Menfi

1976 - Present

HPI: 58.66

Deceased Libyan Politicians

Go to all RankingsMuammar Gaddafi

1942 - 2011

HPI: 85.50

Septimius Severus

145 - 211

HPI: 82.04

Simon of Cyrene

100 BC - 100

HPI: 76.33

Idris of Libya

1889 - 1983

HPI: 73.19

Mahmoud Jibril

1952 - 2020

HPI: 65.66

Hodierna of Jerusalem

1110 - 1164

HPI: 63.38

Gaius Fulvius Plautianus

150 - 205

HPI: 63.26

Pedubast I

900 BC - 793 BC

HPI: 62.43

Muhammad az-Zanati

1944 - 2025

HPI: 61.51

Abdul Ati al-Obeidi

1939 - 2023

HPI: 60.77

Ptolemy Apion

101 BC - 96 BC

HPI: 60.36

Abdurrahim El-Keib

1950 - 2020

HPI: 59.89

Newly Added Libyan Politicians (2025)

Go to all RankingsFathi Bashagha

1962 - Present

HPI: 51.58

Ahmed Maiteeq

1972 - Present

HPI: 42.56

Moussa Ibrahim

1974 - Present

HPI: 37.83

Overlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 15 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.