The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Georgia

This page contains a list of the greatest Georgian Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 119 of which were born in Georgia. This makes Georgia the birth place of the 33rd most number of Politicians behind Bulgaria, and Finland.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Georgian Politicians of all time. This list of famous Georgian Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Georgian Politicians.

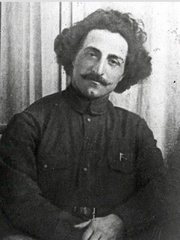

1. Joseph Stalin (1879 - 1953)

With an HPI of 92.22, Joseph Stalin is the most famous Georgian Politician. His biography has been translated into 202 different languages on wikipedia.

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (né Dzhugashvili; 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1878 – 5 March 1953) was a Soviet revolutionary and politician who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held office as General Secretary of the Communist Party from 1922 to 1952 and as premier from 1941 until his death. Despite initially governing the country as part of a collective leadership, he eventually consolidated power to become a dictator by the 1930s. Stalin codified the party's official interpretation of Marxism as Marxism–Leninism, and his version of it is referred to as Stalinism. Born into a poor Georgian family in Gori, Russian Empire, Stalin attended the Tiflis Theological Seminary before joining the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. He raised funds for Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction through bank robberies and other crimes, and edited the party's newspaper, Pravda. He was repeatedly arrested and underwent several exiles to Siberia. After the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution of 1917, Stalin served as a member of the Politburo, and from 1922 used his position as General Secretary to gain control over the party bureaucracy. After Lenin's death in 1924, Stalin won the leadership struggle over rivals including Leon Trotsky. Stalin's doctrine of socialism in one country became central to the party's ideology, and his five-year plans starting in 1928 led to forced agricultural collectivisation, rapid industrialisation, and a centralised command economy. His policies contributed to a famine in 1932–1933 which killed millions, including in the Holodomor in Ukraine. Between 1936 and 1938, Stalin executed hundreds of thousands of his real and perceived political opponents in the Great Purge. Under his regime, an estimated 18 million people passed through the Gulag system of forced labour camps, and more than six million people, including kulaks and entire ethnic groups, were deported to remote areas of the country. Stalin promoted Marxism–Leninism abroad through the Communist International and supported European anti-fascist movements. In 1939, his government signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Germany, enabling the Soviet invasion of Poland at the start of World War II. Germany broke the pact by invading the Soviet Union in 1941, leading Stalin to join the Allies. The Red Army, with Stalin as its commander-in-chief, repelled the German invasion and captured Berlin in 1945, ending the war in Europe. The Soviet Union established Soviet-aligned states in Eastern Europe, and with the United States emerged as a superpower, with the two countries entering a period of rivalry known as the Cold War. Stalin presided over post-war reconstruction and the first Soviet atomic bomb test in 1949. During these years, the country experienced another famine and a state-sponsored antisemitic campaign culminating in the "doctors' plot". In 1953, Stalin died after a stroke. He was succeeded as leader by Georgy Malenkov and eventually Nikita Khrushchev, who in 1956 denounced Stalin's rule and began a campaign of "de-Stalinisation". One of the 20th century's most significant figures, Stalin has a deeply contested legacy. During his rule, he was the subject of a pervasive personality cult within the international Marxist–Leninist movement, which revered him as a champion of socialism and the working class. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Stalin has retained a degree of popularity in some of the post-Soviet states (particularly Russia and Georgia) as an economic moderniser and victorious wartime leader who transformed the Soviet Union into an industrialised superpower. Conversely, his regime has been widely condemned for overseeing mass repression and man-made famine which resulted in the suffering and deaths of millions of Soviet citizens.

2. Darius the Great (550 BC - 486 BC)

With an HPI of 87.66, Darius the Great is the 2nd most famous Georgian Politician. His biography has been translated into 95 different languages.

Darius I (Old Persian: 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 Dārayavaʰuš; c. 550 – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West Asia, parts of the Balkans (Thrace–Macedonia and Paeonia) and the Caucasus, most of the Black Sea's coastal regions, Central Asia, the Indus Valley in the far east, and portions of North Africa and Northeast Africa including Egypt (Mudrâya), eastern Libya, and coastal Sudan. Darius ascended the throne after overthrowing the Achaemenid monarch Bardiya (or Smerdis), who he claimed was in fact an imposter named Gaumata. The new king met with rebellions throughout the empire but quelled each of them; a major event of Darius's career described in Greek historiography was his punitive expedition against Athens and Eretria for their participation in the Ionian Revolt. Darius organized the empire by dividing it into administrative provinces, each governed by a satrap. He organized Achaemenid coinage as a new uniform monetary system, and he made Aramaic a co-official language of the empire alongside Old Persian. He also put the empire in better standing by improving roads and introducing standard weights and measures. Through these changes, the Achaemenid Empire became centralized and unified. Darius undertook other construction projects throughout his realm, primarily focusing on Susa, Pasargadae, Persepolis, Babylon, and Egypt. He had an inscription carved upon a cliff-face of Mount Behistun to record his conquests, which would later become important evidence of the Old Persian language.

3. Attila (406 - 453)

With an HPI of 87.44, Attila is the 3rd most famous Georgian Politician. His biography has been translated into 105 different languages.

Attila ( ə-TIL-ə or AT-il-ə; c. 406 – 453), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in early 453. He was also the leader of an empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Gepids, among others, in Central and Eastern Europe. As nephews to Rugila, Attila and his elder brother Bleda succeeded him to the throne in 435, ruling jointly until the death of Bleda in 445. During his reign, Attila was one of the most feared enemies of the Western and Eastern Roman Empires. He crossed the Danube twice and plundered the Balkans but was unable to take Constantinople. In 441, he led an invasion of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, the success of which emboldened him to invade the West. He also attempted to conquer Roman Gaul (modern France), crossing the Rhine in 451 and marching as far as Aurelianum (Orléans), before being stopped in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains. He subsequently invaded Italy, devastating the northern provinces, but was unable to take Rome. He planned for further campaigns against the Romans but died in 453. After Attila's death, his close adviser, Ardaric of the Gepids, led a Germanic revolt against Hunnic rule, after which the Hunnic Empire quickly collapsed. Attila lived on as a character in Germanic heroic legend.

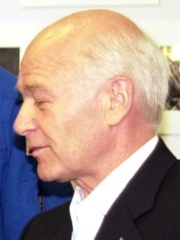

4. Eduard Shevardnadze (1928 - 2014)

With an HPI of 79.00, Eduard Shevardnadze is the 4th most famous Georgian Politician. His biography has been translated into 86 different languages.

Eduard Ambrosis dze Shevardnadze (Georgian: ედუარდ ამბროსის ძე შევარდნაძე; 25 January 1928 – 7 July 2014) was a Soviet and Georgian politician and diplomat who governed Georgia for several non-consecutive periods from 1972 until his resignation in 2003 and also served as the final Soviet minister of foreign affairs from 1985 to 1991. Shevardnadze started his political career in the late 1940s as a leading member of his local Komsomol organisation. He was later appointed its Second Secretary, then its First Secretary. His rise in the Georgian Soviet hierarchy continued until 1961, when he was demoted after insulting a senior official. After spending two years in obscurity, Shevardnadze returned as the First Secretary of a Tbilisi city district, and was able to charge the Tbilisi First Secretary at the time with corruption. His anti-corruption work quickly garnered the interest of the Soviet government and Shevardnadze was appointed as First Deputy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Georgian SSR. He would later become the head of the internal affairs ministry and was able to charge First Secretary (leader of Soviet Georgia) Vasil Mzhavanadze with corruption. He served as First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party (GPC) from 1972 to 1985, which made him the de facto leader of Georgia. As First Secretary, Shevardnadze launched several economic reforms, which would spur economic growth in the republic—an uncommon occurrence in the Soviet Union at the time when the country was experiencing nationwide economic stagnation. Shevardnadze's anti-corruption campaign continued until he resigned from his office as First Secretary of the GPC. In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev appointed Shevardnadze to the position of Minister of Foreign Affairs. He served in the position, except for a brief interruption between 1990 and 1991, until the fall of the Soviet Union. During that time, only Gorbachev outranked Shevardnadze in importance in Soviet foreign policy. Shevardnadze was responsible for many key decisions in Soviet foreign policy during the Gorbachev era and was seen by the outside world as the face of Soviet reforms, such as Perestroika. In the aftermath of the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991, Shevardnadze returned to the newly independent Republic of Georgia after being asked to lead the country by the Military Council, which had recently deposed the country's first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia. In 1992, Shevardnadze became the leader of Georgia (as Chairman of Parliament). He was formally elected as president in 1995. Under his rule, the Sochi agreement was signed, which effectively ended military hostilities in South Ossetia, although Georgia lost effective control over a large part of the territory. In August 1992, the war broke out in Abkhazia, which Georgia also lost. Shevardnadze also headed the country's government during the Georgian Civil War in 1993 against pro-Gamsakhurdia forces, which refused to recognize Shevardnadze as a legitimate leader and tried to regain power. the war ended with Shevardnadze's victory. In this regard, he signed a treaty of Georgia's accession to the Commonwealth of Independent States, in return receiving substantial assistance from Russia to end the conflict, although Georgia also deepened its ties with the European Union and the United States. Consequently, in 1999, he signed the country's accession to the Council of Europe, while in 2002, he declared his intention for Georgia to join NATO. Shevardnadze oversaw large-scale privatization and other political and economic changes. His rule was marked by rampant corruption and accusations of nepotism. Allegations of electoral fraud during the 2003 legislative election led to a series of public protests and demonstrations colloquially known as the Rose Revolution. Eventually, Shevardnadze agreed to resign. He later published his memoirs and lived in relative obscurity until he died in 2014.

5. Tamar of Georgia (1166 - 1213)

With an HPI of 76.80, Tamar of Georgia is the 5th most famous Georgian Politician. Her biography has been translated into 59 different languages.

Tamar the Great (Georgian: თამარ მეფე, romanized: tamar mepe [ˈt̪ʰämäɾ ˈme̞pʰe̞], lit. 'King Tamar'; c. 1160 – 18 January 1213) reigned as the Queen of Georgia from 1184 to 1213, presiding over the apex of the Georgian Golden Age. A member of the Bagrationi dynasty, her position as the first woman to rule Georgia in her own right was emphasized by the title mepe ("king"), afforded to Tamar in the medieval Georgian sources. Tamar was proclaimed heir and co-ruler by her reigning father George III in 1178, but she faced significant opposition from the aristocracy upon her ascension to full ruling powers after George's death. Tamar was successful in neutralizing this opposition and embarked on an energetic foreign policy aided by the decline of the hostile Seljuk Turks. Relying on a powerful military elite, Tamar was able to build on the successes of her predecessors to consolidate an empire which dominated the Caucasus until its collapse under the Mongol attacks within two decades after Tamar's death. Tamar was married twice, her first union being, from 1185 to 1187, to Yury Bogolyubsky of the Grand Principality of Vladimir, whom she divorced and expelled from the country, defeating his subsequent coup attempts. For her second husband Tamar chose, in 1191, the Alan prince David Soslan, by whom she had two children, George and Rusudan, the two successive monarchs on the throne of Georgia. Tamar's reign is associated with a period of marked political and military successes and cultural achievements. This, combined with her role as a female ruler, has contributed to her status as an idealized and romanticized figure in Georgian arts and historical memory. She remains an important symbol in Georgian popular culture.

6. Zviad Gamsakhurdia (1939 - 1993)

With an HPI of 73.86, Zviad Gamsakhurdia is the 6th most famous Georgian Politician. His biography has been translated into 71 different languages.

Zviad Konstantines dze Gamsakhurdia (Georgian: ზვიად კონსტანტინეს ძე გამსახურდია; Russian: Звиа́д Константи́нович Гамсаху́рдия, romanized: Zviad Konstantinovich Gamsakhurdiya; 31 March 1939 – 31 December 1993) was a Georgian politician, human rights activist, dissident, professor of English language studies and American literature at Tbilisi State University, and writer who became the first democratically elected President of Georgia in May 1991. A prominent exponent of Georgian nationalism and pan-Caucasianism, Zviad Gamsakhurdia was involved in Soviet dissident movement from his youth. His activities attracted attention of authorities in the Soviet Union and Gamsakhurdia was arrested and imprisoned numerous times. Gamsakhurdia co-founded the Georgian Helsinki Group, which sought to bring attention to human rights violations in the Soviet Union. He organized numerous pro-independence protests in Georgia, one of which in 1989 was suppressed by the Soviet Army, with Gamsakhurdia being arrested. Eventually, a number of underground political organizations united around Zviad Gamsakhurdia and formed the Round Table—Free Georgia coalition, which successfully challenged the ruling Communist Party of Georgia in the 1990 elections. Gamsakhurdia was elected as the President of Georgia in 1991, gaining 87% of votes in the election. Despite popular support, Gamsakhurdia found significant opposition from the urban intelligentsia and former Soviet nomenklatura, as well as from his own ranks. In early 1992 Gamsakhurdia was overthrown by warlords Tengiz Kitovani, Jaba Ioseliani and Tengiz Sigua, two of which were formerly allied with Gamsakhurdia. Gamsakhurdia was forced to flee to Chechnya, where he was greeted by Chechen president Dzhokhar Dudayev. His supporters continued to fight the post-coup government of Eduard Shevardnadze. In September 1993, Gamsakhurdia returned to Georgia and tried to regain power. Despite initial success, the rebellion was eventually crushed by government forces with the help of the Russian military. Gamsakhurdia was forced into hiding in Samegrelo, a Zviadist stronghold. He was found dead in early 1994 in controversial circumstances. His death remains uninvestigated to this day. After the civil war ended, the government continued to suppress Gamsakhurdia's supporters, even with brutal tactics. After Eduard Shevardnadze was overthrown during the 2003 Rose Revolution, Gamsakhurdia was rehabilitated by the president Mikheil Saakashvili.

7. Kato Svanidze (1885 - 1907)

With an HPI of 71.78, Kato Svanidze is the 7th most famous Georgian Politician. Her biography has been translated into 32 different languages.

Ekaterine "Kato" Svanidze (2 April 1885 – 22 November 1907) was the first wife of Joseph Stalin and the mother of his eldest son, Yakov Dzhugashvili. Born in Racha, in western Georgia, Svanidze eventually moved to Tiflis with her two sisters and brother, and worked as a seamstress. Her brother Alexander was a confidant of Stalin, then still known by his birth name of Ioseb Jughashvili, and introduced him to Svanidze in 1905. They were married in 1906 and she gave birth to son Yakov a few months later. The family moved to Baku to avoid arrest, though Svanidze got quite ill there and returned to Tiflis in 1907, dying shortly after her return, likely from typhoid or tuberculosis. Her death had a profound effect on Stalin, who deeply cared for Svanidze. He abandoned Yakov to be raised by the Svanidze family, and rarely saw them again, fully immersing himself in his revolutionary activities.

8. Mikheil Saakashvili (b. 1967)

With an HPI of 71.33, Mikheil Saakashvili is the 8th most famous Georgian Politician. His biography has been translated into 109 different languages.

Mikheil "Misha" Saakashvili (born 21 December 1967) is a Georgian-Ukrainian politician. He was the third president of Georgia for two consecutive terms from January 2004 to November 2013, with a break from November 2007 to January 2008 after he stepped down following anti-government demonstrations and ahead of an early presidential election. He is the founder and former chairman of Georgia's United National Movement party. From May 2015 until November 2016, Saakashvili was the governor of Ukraine's Odesa Oblast. A jurist by occupation, Saakashvili entered Georgian politics in 1995 as a member of Parliament and Minister of Justice under President Eduard Shevardnadze. He then founded the opposition United National Movement party. In 2003, as a leading opposition figure, he accused the government of rigging the 2003 Georgian parliamentary election, triggering mass street protests and President Shevardnadze's ouster in the bloodless Rose Revolution. Saakashvili's key role in the protests led to his election as president in 2004. He was reelected in 2008. However, his party lost the 2012 Georgian parliamentary election. Term limits meant he could not stand again, and an opposition candidate, nominated by Bidzina Ivanishvili and Coalition Georgian Dream, Giorgi Margvelashvili, won the 2013 presidential election. As president, Saakashvili oversaw far-reaching reforms. His government fired and replaced the entire police force, hoping to root out corruption, and pursued a zero-tolerance policy towards crime. Its neoliberal economic policy abolished various taxes, lowered corporate income tax from 20% to 15% and dividend tax from 10% to 5%. Several ministries were abolished and 60,000 civil servants dismissed, slashing government spending, although the military budget rose to 9.2% of GDP by 2007. In 2009, Forbes ranked Georgia's tax burden as the fourth lowest in the world. GDP grew 70% between 2003 and 2013. Per-capita income roughly tripled, but by 2013 about a quarter of the population was still below the poverty line, even as international perceptions emphasised business-friendliness and reduced corruption. Saakashvili was embroiled in scandals and accused of being behind police brutality, such as the beating of opposition politician Valery Gelashvili, the murder of Sandro Girgvliani, and systemic torture and rape in the Georgian prison system. In late 2013, ex-President Saakashvili left Georgia. In 2014, the Prosecutor's Office of Georgia filed criminal charges against him. In 2018, the Tbilisi City Court sentenced him in absentia to six years in prison for, among other things, ordering Valery Gelashvili's beating. Saakashvili continued to manage his party from abroad. In July 2017, Saakashvili (then visiting the US) was stripped of his Ukrainian citizenship by President Poroshenko, and became stateless. He reentered Ukraine, but was arrested in February 2018 and deported. He was granted permanent residency in the Netherlands, his wife's country. In May 2019, he returned to Ukraine after newly-elected President Volodymyr Zelenskyy restored his citizenship. Zelenskyy appointed Saakashvili to lead Ukraine's National Reform Council in May 2020. In October 2021, Saakashvili announced his return to Georgia after an eight-year absence. Later the same day Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili announced that he had been arrested in Tbilisi. In 2021, he began serving the six-year in absentia prison sentence imposed in 2018. Since May 2022, he has been treated in a civilian clinic in Tbilisi.

9. Rusudan of Georgia (1194 - 1245)

With an HPI of 70.46, Rusudan of Georgia is the 9th most famous Georgian Politician. Her biography has been translated into 30 different languages.

Rusudani (Georgian: რუსუდანი) or Rusudan (Georgian: რუსუდან) (c. 1194–1245), a member of the Bagrationi dynasty, ruled as queen regnant (mepe) of Georgia in 1223–1245.

10. David IV of Georgia (1073 - 1125)

With an HPI of 70.36, David IV of Georgia is the 10th most famous Georgian Politician. His biography has been translated into 52 different languages.

David IV, also known as David IV the Builder (Georgian: დავით IV აღმაშენებელი, romanized: davit IV aghmashenebeli; c. 1073 – 24 January 1125), of the Bagrationi dynasty, was the 5th king (mepe) of the Kingdom of Georgia from 1089 until his death in 1125. Popularly considered to be the greatest and most successful Georgian ruler in history and an original architect of the Georgian Golden Age, he succeeded in driving the Seljuk Turks out of the country, winning the Battle of Didgori in 1121. His reforms of the army and administration enabled him to reunite the country and bring most of the lands of the Caucasus under Georgia's control. A friend of the Church and a notable promoter of Christian culture, he was canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

People

Pantheon has 119 people classified as Georgian politicians born between 550 BC and 1997. Of these 119, 43 (36.13%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Georgian politicians include Mikheil Saakashvili, Bidzina Ivanishvili, and Aslan Abashidze. The most famous deceased Georgian politicians include Joseph Stalin, Darius the Great, and Attila. As of April 2024, 13 new Georgian politicians have been added to Pantheon including Levan Gachechiladze, Levan Varshalomidze, and David Usupashvili.

Living Georgian Politicians

Go to all RankingsMikheil Saakashvili

1967 - Present

HPI: 71.33

Bidzina Ivanishvili

1956 - Present

HPI: 68.95

Aslan Abashidze

1938 - Present

HPI: 63.55

Giorgi Margvelashvili

1969 - Present

HPI: 63.48

Kakha Kaladze

1978 - Present

HPI: 61.46

Nino Burjanadze

1964 - Present

HPI: 60.21

Irakli Kobakhidze

1978 - Present

HPI: 60.21

Giorgi Kvirikashvili

1967 - Present

HPI: 58.22

Irakli Garibashvili

1982 - Present

HPI: 56.32

Giorgi Gakharia

1975 - Present

HPI: 55.24

Vano Merabishvili

1968 - Present

HPI: 54.62

Grigol Vashadze

1958 - Present

HPI: 54.14

Deceased Georgian Politicians

Go to all RankingsJoseph Stalin

1879 - 1953

HPI: 92.22

Darius the Great

550 BC - 486 BC

HPI: 87.66

Attila

406 - 453

HPI: 87.44

Eduard Shevardnadze

1928 - 2014

HPI: 79.00

Tamar of Georgia

1166 - 1213

HPI: 76.80

Zviad Gamsakhurdia

1939 - 1993

HPI: 73.86

Kato Svanidze

1885 - 1907

HPI: 71.78

Rusudan of Georgia

1194 - 1245

HPI: 70.46

David IV of Georgia

1073 - 1125

HPI: 70.36

Sergei Witte

1849 - 1915

HPI: 69.97

Sergo Ordzhonikidze

1886 - 1937

HPI: 69.76

Pharnavaz I of Iberia

326 BC - 234 BC

HPI: 69.08

Newly Added Georgian Politicians (2025)

Go to all RankingsLevan Gachechiladze

1964 - 2025

HPI: 54.55

Levan Varshalomidze

1972 - Present

HPI: 44.39

David Usupashvili

1968 - Present

HPI: 44.08

Eka Zguladze

1978 - Present

HPI: 43.39

Giga Bokeria

1972 - Present

HPI: 43.00

Vakhtang Gomelauri

1974 - Present

HPI: 42.82

Zurab Japaridze

1976 - Present

HPI: 42.18

Tina Bokuchava

1983 - Present

HPI: 41.91

Zaal Udumashvili

1971 - Present

HPI: 41.04

Tina Khidasheli

1973 - Present

HPI: 40.51

Nugzari Tsurtsumia

1997 - 2024

HPI: 37.22

Manuchar Tskhadaia

1985 - Present

HPI: 35.33

Overlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.