The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Afghanistan

This page contains a list of the greatest Afghan Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 117 of which were born in Afghanistan. This makes Afghanistan the birth place of the 34th most number of Politicians behind Finland, and Georgia.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Afghan Politicians of all time. This list of famous Afghan Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Afghan Politicians.

1. Mahmud of Ghazni (971 - 1030)

With an HPI of 80.67, Mahmud of Ghazni is the most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 60 different languages on wikipedia.

Abu al-Qasim Mahmud ibn Sabuktigin (Persian: ابوالقاسم محمود بن سبکتگین, romanized: Abu al-Qāṣim Maḥmūd ibn Sabuktigīn; 2 October 971 – 30 April 1030), usually known as Mahmud of Ghazni or Mahmud Ghaznavi (محمود غزنوی), was Sultan of the Ghaznavid Empire, ruling from 998 to 1030. During his reign and in medieval sources, he is usually known by his honorific title Yamin al-Dawla (یمین الدوله, lit. 'Right Hand of the State'). At the time of his death, his kingdom had been transformed into an extensive military empire, which extended from present-day northwestern Iran proper to the Punjab in the Indian subcontinent, Khwarazm in Transoxiana, and Makran. Highly Persianized, Mahmud continued the bureaucratic, political, and cultural customs of his predecessors, the Samanids. He established the ground for a future Persianate state in Punjab, particularly centered on Lahore, a city he conquered. His capital of Ghazni evolved into a significant cultural, commercial, and intellectual centre in the Islamic world, almost rivalling the important city of Baghdad. The capital appealed to many prominent figures, such as al-Biruni and Ferdowsi. Mahmud ascended the throne at the age of 27 upon his father's death, albeit after a brief war of succession with his brother Ismail. He was the first ruler to hold the title Sultan ("authority"), signifying the extent of his power while at the same time preserving an ideological link to the suzerainty of the Abbasid Caliphs. During his rule, he invaded medieval Punjab 17 times and plundered the richest cities and temple towns, such as Mathura and Somnath, and used the booty to build his capital in Ghazni.

2. Ashraf Ghani (b. 1949)

With an HPI of 78.69, Ashraf Ghani is the 2nd most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 80 different languages.

Mohammad Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai (born 19 May 1949) is an Afghan former politician and economist who served as the 8th and last president of Afghanistan from 2014 when his government was overthrown by the Taliban in 2021. Ghani was born in Logar, then part of the Kingdom of Afghanistan. After his grade-school education in Afghanistan, he spent much of his time abroad, studying in Lebanon and the United States. After receiving his PhD in cultural anthropology from Columbia University in 1983, he taught at various institutions and was an associate professor of anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. For much of the 1990s, he worked at the World Bank. In December 2001, he returned to Afghanistan after the collapse of the Taliban government. He then served as finance minister in Hamid Karzai's cabinet. He resigned in December 2004 to become the dean of Kabul University. In 2009, Ghani ran in the 2009 Afghan presidential election but came in fourth. Ghani became president after winning the controversial 2014 Afghan presidential election. The election was so disputed that negotiations between Ghani and rival Abdullah Abdullah were mediated by the United States. Ghani became president and Abdullah chief executive, with power split 50-50. In 2020, Ghani was re-elected after a delayed result from the 2019 presidential elections. As president, Ghani was known for his intensity and energetic speeches. He aimed to transform Afghanistan into a technocratic state, winning him support from youth and urban demographics. His cabinets were relatively young and well-educated. Ghani made efforts to make peace with Taliban insurgents and improving relations with Pakistan. However many of his promises, such as fighting corruption and turning the country into a trade hub between Central and South Asia, were left unfulfilled. His position was also weakened by political rivalries, his attempt to lessen the power of ex-warlords, and an uneasy relationship with the United States regarding the war. He was also criticized for being aloof and short-tempered, including being in denial during the Taliban's offensive in 2021. On 15 August 2021, his term ended abruptly, as the Taliban took over Kabul. Ghani and staff fled Afghanistan and took refuge in the United Arab Emirates. He later stated he left in order to avoid further violence, and that staying and dying would have accomplished nothing but adding another tragedy to Afghanistan's history. However, he was also condemned across various spectrums for abandoning Afghanistan to the Taliban and has been accused of corruption during his administration. In particular, Ghani's softness on the Taliban was criticized by many.

3. Ahmad Shah Durrani (1722 - 1772)

With an HPI of 78.09, Ahmad Shah Durrani is the 3rd most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 62 different languages.

Ahmad Shah Durrani, (c. 1720–1722 – 16–23 October 1772) born as Ahmad Khan Abdali, was the first ruler and founder of the Durrani Empire. He is often regarded as the founder of modern Afghanistan. As Shah, he relentlessly led military campaigns for over 25 years across West Asia, Central Asia, and South Asia, creating one of the largest Islamic empires in the world, encompassing Afghanistan, much of Pakistan, Iranian Khorasan, and parts of Northern India. Born between 1720 and 1722, Ahmad Shah accompanied Nader Shah in his campaigns until Nader's assassination in 1747, resulting in the division of the Afsharid Empire. Ahmad Shah took advantage and was crowned in Kandahar, establishing his rule in Afghanistan and founding the Durrani Empire. In 1748, he invaded the Mughal Empire and began a series of invasions into India that would span the next 24 years. Following his third invasion of India, Ahmad Shah annexed Punjab and Kashmir from the Mughals. His forays continued, including the occupation and sacking of Delhi in 1757 during his fourth invasion, and the annihilation of Maratha armies at the Third Battle of Panipat, the largest battle of the 18th century, during his fifth. Outside of India, he campaigned in Khorasan and Afghan Turkestan, subjugating the Afsharids, crossing swords with the Khanate of Bukhara, and even encounters with Qing China. In his later reign, he led numerous invasions against the Sikhs to maintain control over the Punjab. Years of nonstop campaigning took a toll on his health, and he died in 1772 in Maruf, being buried in his own mausoleum in Kandahar. Throughout his reign, Ahmad Shah fought over fifteen major military campaigns. Nine of them were centered in India, three in Khorasan, and three in Afghan Turkestan. Having rarely lost a battle, historians widely recognize Ahmad Shah as a brilliant military leader and tactician, typically being compared to military leaders such as Marlborough, Mahmud of Ghazni, Babur, and Nader Shah. Ahmad Shah has been described as one of the greatest military leaders of eighteenth century Asia, as well the "greatest general of Asia of his time", and as one of the greatest conquerors in Asian history.

4. Abbas the Great (1571 - 1629)

With an HPI of 77.08, Abbas the Great is the 4th most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 77 different languages.

Abbas I (Persian: عباس یکم, romanized: Abbâs-e Yekom; 27 January 1571 – 19 January 1629), commonly known as Abbas the Great (Persian: عباس بزرگ, romanized: Abbâs-e Bozorg), was the fifth Safavid shah of Iran from 1588 to 1629. The third son of Shah Mohammad Khodabanda, he is generally considered one of the most important rulers in Iranian history and the greatest ruler of the Safavid dynasty. Although Abbas would reign over Safavid Iran at its military, political and economic height, he came to the throne during a period of instability in the empire. Under the ineffective rule of his father, the country was riven with discord between the different factions of the Qizilbash army, who killed Abbas' mother and elder brother. Meanwhile, Iran's main enemies, its arch-rival the Ottoman Empire and the Uzbeks, exploited this political chaos to seize territory for themselves. In 1588, one of the Qizilbash leaders, Murshid Quli Khan, overthrew Shah Mohammed in a coup and placed the 16-year-old Abbas on the throne. However, Abbas soon seized power for himself. Under his leadership, Iran developed the ghilman system where thousands of Circassian, Georgian, and Armenian slave-soldiers joined the civil administration and the military, thus creating a new strata in Iranian society, this was initiated by his predecessors but significantly expanded during his rule. This allowed Abbas to eclipse the power of the Qizilbash in the civil administration, the royal house, and the military. These actions, as well as his reforms of the Iranian army, enabled him to fight the Ottomans and Uzbeks and reconquer Iran's lost provinces, including Kakheti, whose people he subjected to widescale massacres and deportations. By the end of the 1603–1618 Ottoman War, Abbas had regained possession over South Caucasus and Dagestan, as well as swaths of Western Armenia and Mesopotamia. He also took back land from the Portuguese and the Mughals and expanded Iranian rule and influence in the North Caucasus, beyond the traditional territories of Dagestan. Abbas was a great builder and moved the empire's capital from Qazvin to Isfahan, and transformed the city into a masterpiece of Safavid architecture. In his later years, following a court intrigue involving several leading Circassians, Abbas became suspicious of his own sons and had them killed or blinded. Shah Abbas changed the empire, which was mainly held together by the strong beliefs of several militant tribes (Qizilbash), into a unified and stable monarchy. He strengthened the state by securing its borders, improving its economy, setting up a centralised administration, and creating a regular army (Shahsavan) that reported directly to him instead of tribal leaders. His keen economic and commercial understanding brought wealth and prosperity to the nation. Internal stability and consistent regulations encouraged agricultural growth. Infrastructure projects which included roads and public buildings, were carried out on an unprecedented scale, and enabled the flourishing of crafts and industries. As a skilled diplomat with a broad outlook, Shah Abbas sought political and economic ties with Western countries, and foreign ambassadors were warmly welcomed at his court.

5. Mohammed Zahir Shah (1914 - 2007)

With an HPI of 76.65, Mohammed Zahir Shah is the 5th most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 64 different languages.

Mohammad Zahir Shah (15 October 1914 – 23 July 2007) was the last king of Afghanistan, reigning from 8 November 1933 until he was deposed on 17 July 1973. Ruling for 40 years, Zahir Shah was the longest-serving ruler of Afghanistan since the foundation of the Durrani Empire in the 18th century. He expanded Afghanistan's diplomatic relations with many countries, including with both sides of the Cold War. In the 1950s, Zahir Shah began modernizing the country, culminating in the creation of a new constitution and a constitutional monarchy system. Demonstrating nonpartisanism, his long reign was marked by peace in the country which was lost afterwards with the onset of the Afghan conflict. In 1973, while Zahir Shah was undergoing medical treatment in Italy, his regime was overthrown in a coup d'état by his cousin and former prime minister, Sardar Mohammad Daoud Khan, who established a single-party republic, ending more than 225 years of continuous monarchical government. He remained in exile near Rome until 2002, returning to Afghanistan after the end of the Taliban government. He was given the title Father of the Nation, which he held until his death in 2007.

6. Hamid Karzai (b. 1957)

With an HPI of 76.45, Hamid Karzai is the 6th most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 88 different languages.

Hamid Karzai (born 24 December 1957) is an Afghan politician who served as the seventh president of Afghanistan from 2002 to 2014, including as the first president of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan from 2004 to 2014. He also served as chairman of the Afghan Interim Administration from 2001 to 2002. Born in Kandahar, Karzai graduated from Habibia High School in Kabul and later received a master's degree from Himachal Pradesh University, Summerhill, Shimla, India, in the 1980s. He moved to Pakistan where he was active as a fundraiser for the Afghan mujahideen during the Soviet–Afghan War (1979–1989) and its aftermath. He briefly served as Deputy Foreign Minister in the Islamic State of Afghanistan government. In July 1999, Karzai's father was assassinated and Karzai succeeded him as head of the Popalzai tribe. In October 2001 the United States invasion of Afghanistan began and Karzai led the Pashtun tribes in and around Kandahar in an uprising against the Taliban; he became a dominant political figure after the removal of the Taliban regime in late 2001. During the December 2001 International Conference on Afghanistan in Germany, Karzai was selected by prominent Afghan political figures to serve a six-month term as chairman of the Interim Administration. He was then chosen for a two-year term as interim president during the 2002 loya jirga (grand assembly) that was held in Kabul, Afghanistan. After the 2004 presidential election, Karzai was declared the winner and became President of Afghanistan. He won a second five-year term in the 2009 presidential election; this term ended in September 2014, and he was succeeded by Ashraf Ghani. During his presidency, Karzai was known in the international community for being an alliance builder between Afghanistan's multi-ethnic communities. He also strengthened Afghanistan–Pakistan relations. In later years, his relationship with NATO and the United States became increasingly strained. Karzai's stance on extremism and terrorism was criticized; he described the Taliban as his brothers, and warned that the heavy-handed counterinsurgency in Afghanistan would only revive the Taliban insurgency against the former Afghan government, urging the US to instead focus on subduing Pakistan's support for the Taliban leadership, but the US largely ignored his requests. Karzai was also accused of corruption. After the Taliban takeover of Kabul in 2021, Karzai stated the Taliban did not capture the city by force, but rather were invited by him in order to prevent chaos. He said that in order to gain international recognition, the new Taliban government needed internal legitimacy, which could be achieved through a general election or loya jirga.

7. Amanullah Khan (1892 - 1960)

With an HPI of 75.51, Amanullah Khan is the 7th most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 51 different languages.

Ghazi Amanullah Khan Barakzai (1 June 1892 – 26 April 1960) was Emir of Afghanistan from 1919 to 1926, and then King of Afghanistan from 1926 until his abdication in 1929. After the end of the Third Anglo-Afghan War in August 1919, Afghanistan was able to relinquish its protected state status to proclaim independence and pursue an independent foreign policy free from the influence of the United Kingdom. His rule was marked by dramatic political and social change, including attempts to modernize Afghanistan along Western lines. He did not fully succeed in achieving this objective due to an uprising by Habibullah Kalakani and his followers. On 14 January 1929, Amanullah abdicated and fled to neighbouring British India as the Afghan Civil War began to escalate. From British India, he went to Europe, where after 30 years in exile, he died in Zürich, Switzerland on 26 April 1960. His body was brought to Afghanistan and buried in Jalalabad near his father Habibullah Khan's tomb.

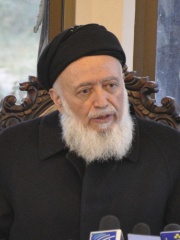

8. Hasan Akhund (b. 1945)

With an HPI of 75.51, Hasan Akhund is the 8th most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 43 different languages.

Muhammad Hasan Akhund Kakar (born c. 1945–1958) is an Afghan politician and cleric who has been serving as the 27th prime minister of Afghanistan since 2025, having previously served in this role on an interim basis from 2021. A member of the Taliban, he has been a Member of the Leadership Council since 2002, and previously served as deputy prime minister from 1996 to 2001, and the Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1998 to 1999. Akhund is one of the founding members of the Taliban and has been a senior leading member of the movement. In the first Taliban government (1996–2001), he served as the deputy foreign minister.

9. Burhanuddin Rabbani (1940 - 2011)

With an HPI of 75.48, Burhanuddin Rabbani is the 9th most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 57 different languages.

Burhanuddin Rabbani (20 September 1940 – 20 September 2011) was an Afghan politician and teacher who served as the sixth president of Afghanistan from 1992 to 1996, and again from November to December 2001 (in exile from 1996 to 2001). Born in the Badakhshan Province, Rabbani studied at Kabul University and worked there as a professor of Islamic theology. He formed the Jamiat-e Islami at the university which attracted then-students Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Ahmad Shah Massoud, both would eventually become the two leading commanders of the Afghan mujahideen in the Soviet–Afghan War from 1979. Rabbani was chosen to be the President of Afghanistan after the end of the former communist regime in 1992. Rabbani and his Islamic State of Afghanistan government was later forced into exile by the Taliban, and he then served as the political head of the Northern Alliance, an alliance of various political groups who fought against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. During his time in the office, there were a lot of internal clashes between different fighting groups. After the Taliban government was toppled during Operation Enduring Freedom, Rabbani returned to Kabul and served briefly as president from 13 November to 22 December 2001, when Hamid Karzai was chosen as his succeeding interim leader at the Bonn International Conference. In later years he became head of Afghanistan National Front (known in the media as United National Front), the largest political opposition to Karzai's government. On 20 September 2011, Rabbani was assassinated by a suicide bomber entering his home in Kabul. As suggested by the Afghan parliament, Afghanistan's President Hamid Karzai gave him the title of "Martyr of Peace". His son Salahuddin Rabbani was chosen in April 2012 to lead efforts to forge peace in Afghanistan with the Taliban.

10. Mohammed Daoud Khan (1909 - 1978)

With an HPI of 75.36, Mohammed Daoud Khan is the 10th most famous Afghan Politician. His biography has been translated into 48 different languages.

Mohammad Daoud Khan, (18 July 1909 – 28 April 1978), also romanized as Daud Khan or Dawood Khan, was an Afghan military officer and politician who served as prime minister of Afghanistan from 1953 to 1963 and, as leader of the 1973 Afghan coup d'état which overthrew the monarchy, served as the first president of Afghanistan from 1973 until his assassination in 1978. Born into the Afghan royal family and addressed by the prefix "Sardar", Khan started as a provincial governor and later a military officer before being appointed as prime minister by his cousin, King Mohammad Zahir Shah, serving for a decade. Having failed to persuade the King to implement a one-party system, Khan overthrew the monarchy in a virtually bloodless coup with the backing of Afghan Army officers, and proclaimed himself the first president of the Republic of Afghanistan, establishing an autocratic one-party system under his National Revolutionary Party. Khan was known for his autocratic rule, and for his educational and progressive social reforms. Under his regime, he headed a purge of communists in the government, and many of his policies also displeased Islamic religious conservatives and liberals who were in favor of restoring the multiparty system that existed under the monarchy. Social and economic reforms implemented under his ruling were successful, but his foreign policy led to tense relations with neighboring countries. In 1978, he was deposed and assassinated during the 1978 Afghan coup d'état, led by the Afghan military and the communist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). His body was discovered 30 years later and was identified by a small golden Quran gifted by King Khalid of Saudi Arabia he always carried. He received a state funeral.

People

Pantheon has 117 people classified as Afghan politicians born between 327 BC and 1992. Of these 117, 34 (29.06%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Afghan politicians include Ashraf Ghani, Hamid Karzai, and Hasan Akhund. The most famous deceased Afghan politicians include Mahmud of Ghazni, Ahmad Shah Durrani, and Abbas the Great. As of April 2024, 9 new Afghan politicians have been added to Pantheon including Fatima Aziz, Obaidullah Akhund, and Mustafa Nayyem.

Living Afghan Politicians

Go to all RankingsAshraf Ghani

1949 - Present

HPI: 78.69

Hamid Karzai

1957 - Present

HPI: 76.45

Hasan Akhund

1945 - Present

HPI: 75.51

Hibatullah Akhundzada

1961 - Present

HPI: 72.74

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar

1949 - Present

HPI: 72.44

Abdul Rashid Dostum

1954 - Present

HPI: 65.85

Abdul Ghani Baradar

1968 - Present

HPI: 63.48

Ismail Khan

1946 - Present

HPI: 62.08

Abdul Rasul Sayyaf

1946 - Present

HPI: 61.70

Abdullah Abdullah

1960 - Present

HPI: 61.41

Suhail Shaheen

HPI: 59.15

Abdul Kabir

1958 - Present

HPI: 58.40

Deceased Afghan Politicians

Go to all RankingsMahmud of Ghazni

971 - 1030

HPI: 80.67

Ahmad Shah Durrani

1722 - 1772

HPI: 78.09

Abbas the Great

1571 - 1629

HPI: 77.08

Mohammed Zahir Shah

1914 - 2007

HPI: 76.65

Amanullah Khan

1892 - 1960

HPI: 75.51

Burhanuddin Rabbani

1940 - 2011

HPI: 75.48

Mohammed Daoud Khan

1909 - 1978

HPI: 75.36

Mohammad Najibullah

1947 - 1996

HPI: 75.28

Ahmad Shah Massoud

1953 - 2001

HPI: 75.21

Dost Mohammad Khan

1793 - 1863

HPI: 74.95

Muhammad of Ghor

1160 - 1206

HPI: 74.64

Mohammed Omar

1962 - 2013

HPI: 74.34

Newly Added Afghan Politicians (2025)

Go to all RankingsFatima Aziz

HPI: 44.50

Obaidullah Akhund

HPI: 43.59

Mustafa Nayyem

1981 - Present

HPI: 43.25

Abdul Salam Hanafi

HPI: 43.17

Khalil Haqqani

1966 - 2024

HPI: 42.25

Nasima Razmyar

1984 - Present

HPI: 37.62

Maryam Durani

HPI: 35.66

Rada Akbar

HPI: 34.07

Muqadasa Ahmadzai

HPI: 32.27

Overlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.