The Most Famous

PHILOSOPHERS from France

This page contains a list of the greatest French Philosophers. The pantheon dataset contains 1,267 Philosophers, 138 of which were born in France. This makes France the birth place of the 2nd most number of Philosophers.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary French Philosophers of all time. This list of famous French Philosophers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of French Philosophers.

1. René Descartes (1596 - 1650)

With an HPI of 92.12, René Descartes is the most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 178 different languages on wikipedia.

René Descartes ( day-KART, also UK: DAY-kart, French: [ʁəne dekaʁt] ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathematics was paramount to his method of inquiry, and he connected the previously separate fields of geometry and algebra into analytic geometry. Refusing to accept the authority of previous philosophers, Descartes frequently set his views apart from the philosophers who preceded him. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul, an early modern treatise on emotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic "as if no one had written on these matters before." His best known philosophical statement is "cogito, ergo sum" ("I think, therefore I am," French: "Je pense, donc je suis"). Descartes has often been called the father of modern philosophy, and he is largely seen as responsible for the increased attention given to epistemology in the 17th century. He was one of the key figures in the Scientific Revolution, and his Meditations on First Philosophy and other philosophical works continue to be studied. His influence in mathematics is equally apparent, being the namesake of the Cartesian coordinate system. Descartes is also credited as the father of analytic geometry, which facilitated the discovery of infinitesimal calculus and analysis.

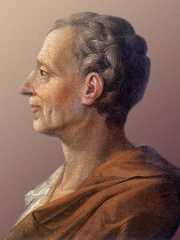

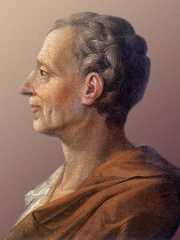

2. Montesquieu (1689 - 1755)

With an HPI of 87.46, Montesquieu is the 2nd most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 104 different languages.

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 1689 – 10 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, intellectual, historian, and political philosopher. He is the principal source of the theory of separation of powers, which is implemented in many constitutions throughout the world. He is also known for doing more than any other author to secure the place of the word despotism in the political lexicon. His anonymously published The Spirit of Law (De l'esprit des lois, 1748) first translated into English (Nugent) in a 1750 edition was received well in both Great Britain and the American colonies, and influenced the Founding Fathers of the United States in drafting the U.S. Constitution.

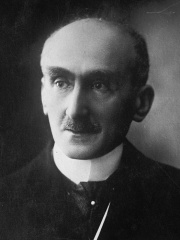

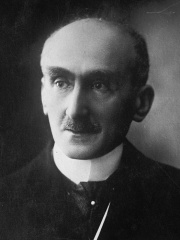

3. Auguste Comte (1798 - 1857)

With an HPI of 85.43, Auguste Comte is the 3rd most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 97 different languages.

Isidore Auguste Marie François Xavier Comte (; French: [oɡyst(ə) kɔ̃t] ; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher, mathematician and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term. Comte's ideas were also fundamental to the development of sociology, with him inventing the very term and treating the discipline as the crowning achievement of the sciences. Influenced by Henri de Saint-Simon, Comte's work attempted to remedy the social disorder caused by the French Revolution, which he believed indicated an imminent transition to a new form of society. He sought to establish a new social doctrine based on science, which he labeled positivism. He had a major impact on 19th-century thought, influencing the work of social thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and George Eliot. His concept of Sociology and social evolutionism set the tone for early social theorists and anthropologists such as Harriet Martineau and Herbert Spencer, evolving into modern academic sociology presented by Émile Durkheim as practical and objective social research. Comte's social theories culminated in his "Religion of Humanity", which presaged the development of non-theistic religious humanist and secular humanist organizations in the 19th century. He may also have coined the word altruism.

4. Michel de Montaigne (1533 - 1592)

With an HPI of 83.66, Michel de Montaigne is the 4th most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 87 different languages.

Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne (28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592), commonly known as just Michel de Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularising the essay as a literary genre. His work is noted for its merging of casual anecdotes and autobiography with intellectual insight. Montaigne had a direct influence on numerous writers of Western literature; his Essais contain some of the most influential essays ever written. During his lifetime, Montaigne was admired more as a statesman than as an author. The tendency in his essays to digress into anecdotes and personal ruminations was seen as detrimental to proper style, rather than as an innovation; moreover, his declaration that "I am myself the matter of my book" was viewed by his contemporaries as self-indulgent. In time, however, Montaigne came to be recognised as embodying the spirit of critical thought and open inquiry that began to emerge around that time. He is best known for his sceptical remark, "Que sçay-je ?" ("What do I know?", in Middle French; "Que sais-je ?" in modern French).

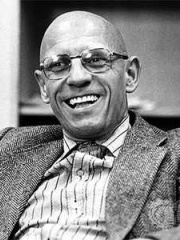

5. Michel Foucault (1926 - 1984)

With an HPI of 82.59, Michel Foucault is the 5th most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 93 different languages.

Paul-Michel Foucault (UK: FOO-koh, US: foo-KOH; French: [pɔl miʃɛl fuko]; 15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984) was a French historian of ideas and philosopher, who was also an author, literary critic, political activist, and teacher. Foucault's theories primarily addressed the relationships between power versus knowledge and liberty, and he analyzed how they are used as a form of social control through multiple institutions. Though often cited as a structuralist and postmodernist, Foucault rejected these labels and sought to critique authority without limits on himself. His thought has influenced academics within a large number of contrasting areas of study, with this especially including those working in anthropology, communication studies, criminology, cultural studies, feminism, literary theory, psychology, and sociology. His efforts against homophobia and racial prejudice as well as against other ideological doctrines have also shaped research into critical theory and Marxism–Leninism alongside other topics. Born in Poitiers, France, into an upper-middle-class family, Foucault was educated at the Lycée Henri-IV, at the École Normale Supérieure, where he developed an interest in philosophy and came under the influence of his tutors Jean Hyppolite and Louis Althusser, and at the University of Paris (Sorbonne), where he earned degrees in philosophy and psychology. After several years as a cultural diplomat abroad, he returned to France and published his first major book, The History of Madness (1961). After obtaining work between 1960 and 1966 at the University of Clermont-Ferrand, he produced The Birth of the Clinic (1963) and The Order of Things (1966), publications that displayed his increasing involvement with structuralism, from which he later distanced himself. These first three histories exemplified a historiographical technique Foucault was developing, which he called "archaeology". From 1966 to 1968, Foucault lectured at the University of Tunis, before returning to France, where he became head of the philosophy department at the new experimental university of Paris VIII. Foucault subsequently published The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969). In 1970, Foucault was admitted to the Collège de France, a membership he retained until his death. He also became active in several left-wing groups involved in campaigns against racism and other violations of human rights, focusing on struggles such as penal reform. Foucault later published Discipline and Punish (1975) and The History of Sexuality (1976), in which he developed archaeological and genealogical methods that emphasized the role that power plays in society. Foucault died in Paris from complications of HIV/AIDS. He became the first public figure in France to die from complications of the disease, with his charisma and career influence changing mass awareness of the pandemic. This occurrence influenced HIV/AIDS activism; his partner, Daniel Defert, founded the AIDES charity in his memory. It continues to campaign as of 2024, despite the deaths of both Defert (in 2023) and Foucault (in 1984).

6. Henri Bergson (1859 - 1941)

With an HPI of 82.22, Henri Bergson is the 6th most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 96 different languages.

Henri-Louis Bergson (; French: [bɛʁksɔn]; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopher who was influential in the traditions of analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, especially during the first half of the 20th century until the Second World War, but also after 1966 when Gilles Deleuze published Le Bergsonisme. Bergson is known for his arguments that processes of immediate experience and intuition are more significant than abstract rationalism and science for understanding reality. Bergson was awarded the 1927 Nobel Prize in Literature "in recognition of his rich and vitalizing ideas and the brilliant skill with which they have been presented". In 1930, France awarded him its highest honour, the Grand-Croix de la Legion d'honneur. Bergson's great popularity created a controversy in France, where his views were seen as opposing the "secular and scientific" attitude adopted by the Republic's officials.

7. Peter Abelard (1079 - 1142)

With an HPI of 80.63, Peter Abelard is the 7th most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 74 different languages.

Peter Abelard (12 February 1079 – 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, teacher, musician, composer, and poet. In philosophy he is celebrated for his logical solution to the problem of universals via nominalism and conceptualism and his pioneering of intent in ethics. Often referred to as the "Descartes of the twelfth century", he is considered a forerunner of Rousseau, Kant, and Spinoza. He is sometimes credited as a chief forerunner of modern empiricism. In Catholic theology, he is best known for his development of the concept of limbo, and his introduction of the moral influence theory of atonement. He is considered (alongside Augustine) to be the most significant forerunner of the modern self-reflective autobiographer. He paved the way and set the tone for later epistolary novels and celebrity tell-alls with his publicly distributed letter, The History of My Calamities, and public correspondence. In history and popular culture he is best known for his passionate, tragic love affair and intense philosophical exchange with his brilliant student and eventual wife, Héloïse d'Argenteuil.

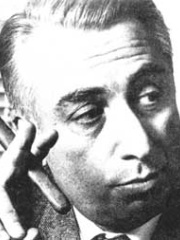

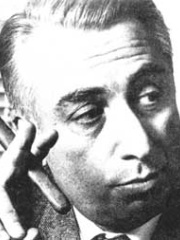

8. Roland Barthes (1915 - 1980)

With an HPI of 80.26, Roland Barthes is the 8th most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 67 different languages.

Roland Gérard Barthes (; French: [ʁɔlɑ̃ baʁt]; 12 November 1915 – 26 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign systems, mainly derived from Western popular culture. His ideas explored a diverse range of fields and influenced the development of multiple schools of theory, including structuralism, anthropology, literary theory, and post-structuralism. Barthes is perhaps best known for his 1957 essay collection Mythologies, which contained reflections on popular culture, and the 1967/1968 essay "The Death of the Author", which critiqued traditional approaches in literary criticism. During his academic career he was primarily associated with the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) and the Collège de France.

9. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809 - 1865)

With an HPI of 79.12, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon is the 9th most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 75 different languages.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, also US: ; French: [pjɛʁ ʒozɛf pʁudɔ̃]; 15 January 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to call himself an anarchist, and is widely regarded as one of anarchism's most influential theorists. Proudhon became a member of the French Parliament after the Revolution of 1848, whereafter he referred to himself as a federalist. Proudhon described the liberty he pursued as the synthesis of community and individualism. Some consider his mutualism to be part of individualist anarchism while others regard it to be part of social anarchism. Proudhon, who was born in Besançon, was a printer who taught himself Latin in order to better print books in the language. His best-known assertion is that "property is theft!", contained in his first major work, What Is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government (Qu'est-ce que la propriété? Recherche sur le principe du droit et du gouvernement), published in 1840. The book's publication attracted the attention of the French authorities. It also attracted the scrutiny of Karl Marx, who started a correspondence with its author. The two influenced each other and they met in Paris while Marx was exiled there. Their friendship finally ended when Marx responded to Proudhon's The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty with the provocatively titled The Poverty of Philosophy. The dispute became one of the sources of the split between the anarchist and Marxist wings of the International Working Men's Association. Some such as Edmund Wilson have contended that Marx's attack on Proudhon had its origin in the latter's defense of Karl Grün, whom Marx bitterly disliked, but who had been preparing translations of Proudhon's work. Proudhon favored workers' councils and associations or cooperatives as well as individual worker/peasant possession over private ownership or the nationalization of land and workplaces. He considered social revolution to be achievable in a peaceful manner. Proudhon unsuccessfully tried to create a national bank, to be funded by what became an abortive attempt at an income tax on capitalists and shareholders. Similar in some respects to a credit union, it would have given interest-free loans. After the death of his follower Mikhail Bakunin, Proudhon's libertarian socialism diverged into individualist anarchism, collectivist anarchism, anarcho-communism and anarcho-syndicalism, with notable proponents such as Carlo Cafiero, Joseph Déjacque, Peter Kropotkin and Benjamin Tucker.

10. Jean Bodin (1530 - 1596)

With an HPI of 78.77, Jean Bodin is the 10th most famous French Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 53 different languages.

Jean Bodin (; French: [ʒɑ̃ bɔdɛ̃]; c. 1530 – 1596) was a French jurist and political philosopher, member of the Parlement of Paris and professor of law in Toulouse. Bodin lived during the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and wrote against the background of religious conflict in France. He seemed to be a nominal Catholic throughout his life but was critical of papal authority over governments. Known for his theory of sovereignty, he favoured the strong central control of a national monarchy as an antidote to factional strife. Towards the end of his life he wrote a dialogue among different religions, including representatives of Judaism, Islam and natural theology in which all agreed to coexist in concord, but was not published. He was also an influential writer on demonology, as his later years were spent during the peak of the early modern witch trials.

People

Pantheon has 138 people classified as French philosophers born between 85 and 1967. Of these 138, 11 (7.97%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living French philosophers include Edgar Morin, Alain de Benoist, and Étienne Balibar. The most famous deceased French philosophers include René Descartes, Montesquieu, and Auguste Comte.

Living French Philosophers

Go to all RankingsEdgar Morin

1921 - Present

HPI: 68.66

Alain de Benoist

1943 - Present

HPI: 67.91

Étienne Balibar

1942 - Present

HPI: 64.24

Jean-Luc Marion

1946 - Present

HPI: 61.96

Alain Finkielkraut

1949 - Present

HPI: 60.52

Élisabeth Badinter

1944 - Present

HPI: 59.65

Rémi Brague

1947 - Present

HPI: 58.23

Michel Onfray

1959 - Present

HPI: 58.07

André Comte-Sponville

1952 - Present

HPI: 55.47

Barbara Cassin

1947 - Present

HPI: 55.26

Quentin Meillassoux

1967 - Present

HPI: 54.29

Deceased French Philosophers

Go to all RankingsRené Descartes

1596 - 1650

HPI: 92.12

Montesquieu

1689 - 1755

HPI: 87.46

Auguste Comte

1798 - 1857

HPI: 85.43

Michel de Montaigne

1533 - 1592

HPI: 83.66

Michel Foucault

1926 - 1984

HPI: 82.59

Henri Bergson

1859 - 1941

HPI: 82.22

Peter Abelard

1079 - 1142

HPI: 80.63

Roland Barthes

1915 - 1980

HPI: 80.26

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

1809 - 1865

HPI: 79.12

Jean Bodin

1530 - 1596

HPI: 78.77

Gilles Deleuze

1925 - 1995

HPI: 78.10

Henri de Saint-Simon

1760 - 1825

HPI: 77.38

Overlapping Lives

Which Philosophers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Philosophers since 1700.