The Most Famous

WRITERS from Ukraine

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Ukrainian Writers of all time. This list of famous Ukrainian Writers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Ukrainian Writers.

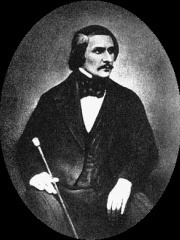

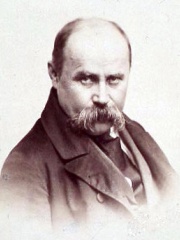

1. Nikolai Gogol (1809 - 1852)

With an HPI of 82.82, Nikolai Gogol is the most famous Ukrainian Writer. His biography has been translated into 107 different languages on wikipedia.

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol (1 April [O.S. 20 March] 1809 – 4 March [O.S. 21 February] 1852) was a Russian novelist, short-story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin. Gogol used the grotesque in his writings, for example in his works "The Nose", "Viy", "The Overcoat", and "Nevsky Prospekt". These stories, and others such as "Diary of a Madman", have also been noted for their proto-surrealist qualities. According to Viktor Shklovsky, Gogol used the technique of defamiliarization, whereby a writer presents common things in an unfamiliar or strange way so that the reader can gain new perspectives and see the world differently. His early works, such as Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, were influenced by his Ukrainian upbringing, Ukrainian culture and folklore. His later writing satirised political corruption in contemporary Russia (The Government Inspector, Dead Souls), although Gogol also enjoyed the patronage of Tsar Nicholas I, who liked his work. The novel Taras Bulba (1835), the play Marriage (1842), and the short stories "The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich", "The Portrait", and "The Carriage" are also among his best-known works. Many writers and critics have recognized Gogol's deep influence on Russian, Ukrainian and world literature. Gogol's influence was acknowledged by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Franz Kafka, Mikhail Bulgakov, Vladimir Nabokov, Flannery O'Connor and others. Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé said: "We all came out from under Gogol's Overcoat."

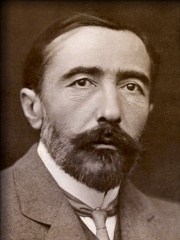

2. Mikhail Bulgakov (1891 - 1940)

With an HPI of 78.73, Mikhail Bulgakov is the 2nd most famous Ukrainian Writer. His biography has been translated into 90 different languages.

Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov ( buul-GAH-kof; Russian: Михаил Афанасьевич Булгаков, IPA: [mʲɪxɐˈil ɐfɐˈnasʲjɪvʲɪdʑ bʊlˈɡakəf] 15 May [O.S. 3 May] 1891 – 10 March 1940) was a Russian and Soviet novelist and playwright. His novel The Master and Margarita, published posthumously, has been called one of the masterpieces of the 20th century. He also wrote the novel The White Guard and the plays Ivan Vasilievich, Flight (also called The Run), and The Days of the Turbins. Some of his works (Flight, all his works between 1922 and 1926, and others) were banned by the Soviet government, and personally by Joseph Stalin, after it was decided by them that they "glorified emigration and White generals". On the other hand, Stalin loved Bulgakov's dramatization of The White Guard, anodynely renamed The Days of the Turbins. The Soviet leader reportedly attended the play at least 15 times, even calling a theater to personally demand its production after the playwright's fall from favor. Despite Stalin's intercession in this and other matters Bulgakov was only briefly successful during his lifetime. After his death, especially once the publication of The Master and Margarita had been accomplished in 1966-67, his work was reassessed. He is now widely regarded as one of the great Russian authors of the 20th century.

3. Taras Shevchenko (1814 - 1861)

With an HPI of 78.66, Taras Shevchenko is the 3rd most famous Ukrainian Writer. His biography has been translated into 105 different languages.

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko (Ukrainian: Тарас Григорович Шевченко; Russian: Тарас Григорьевич Шевченко, romanized: Taras Grigoryevich Shevchenko; 9 March 1814 – 10 March 1861) was a Ukrainian poet, writer, artist, public and political figure, folklorist, and ethnographer. He wrote poetry in Ukrainian and prose (nine novellas, a diary, and his autobiography) in Russian. Born to a poor family of serfs during the period of Russian rule over Ukraine, in his youth Shevchenko demonstrated a talent for art and become a fellow of the Imperial Academy in St. Petersburg. After his return to Ukraine, he joined the emerging national movement. Exiled to Central Asia due to his association with the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, Shevchenko continued to create art and poetry despite prohibitions, and his figure attained fame among the liberal-minded circles of the Russian Empire. Freed from exile after the onset of liberal reforms of Alexander II, Shevchenko was prohibited from settling in Ukraine and died in Saint Petersburg. His literary heritage, in particular the poetry collection Kobzar, is regarded to be the foundation of modern Ukrainian literature and to some degree also of the modern Ukrainian language. The significance of Shevchenko's creative genius for the Ukrainian and wider Slavic culture has led some to compare his figure to that of Robert Burns.

4. Joseph Conrad (1857 - 1924)

With an HPI of 78.29, Joseph Conrad is the 4th most famous Ukrainian Writer. His biography has been translated into 88 different languages.

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, Polish: [ˈjuzɛf tɛˈɔdɔr ˈkɔnrat kɔʐɛˈɲɔfskʲi] ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the English language and – though he did not speak English fluently until his twenties (always with a strong foreign accent) – he became a master prose stylist who brought a non-English sensibility into English literature. He wrote novels and stories, many in nautical settings, that depicted crises of human individuality in the midst of what he saw as an indifferent, inscrutable, and amoral world. Conrad is considered a literary impressionist by some and an early modernist by others, though his works also contain elements of 19th-century realism. His narrative style and anti-heroic characters, as in Lord Jim, have influenced numerous authors. Many dramatic films have been adapted from and inspired by his works. Numerous writers and critics have commented that his fictional works, written mostly in the first two decades of the 20th century, seem to have anticipated later world events. Writing near the peak of the British Empire, Conrad drew on the national experiences of his native Poland—during nearly all his life, parcelled out among three occupying empires—and on his own experiences in the French and British merchant navies, to create short stories and novels that reflect aspects of a European-dominated world—including imperialism and colonialism—and that profoundly explore the human psyche.

5. Svetlana Alexievich (b. 1948)

With an HPI of 78.14, Svetlana Alexievich is the 5th most famous Ukrainian Writer. Her biography has been translated into 98 different languages.

Svetlana Alexandrovna Alexievich (born 31 May 1948) is a Belarusian investigative journalist, essayist and oral historian who writes in Russian. She was awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature "for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time". She is the first writer from Belarus to receive the award.

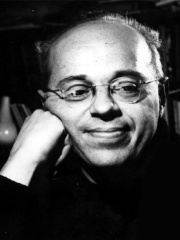

6. Stanisław Lem (1921 - 2006)

With an HPI of 77.56, Stanisław Lem is the 6th most famous Ukrainian Writer. His biography has been translated into 79 different languages.

Stanisław Herman Lem (Polish: [staˈɲiswaf ˈlɛm] ; 12 September 1921 – 27 March 2006) was a Polish writer. He was the author of many novels, short stories, and essays on various subjects, including philosophy, futurology, and literary criticism. Many of his science fiction stories are of satirical and humorous character. Lem's books have been translated into more than 50 languages and have sold more than 45 million copies. Worldwide, he is best known as the author of the 1961 novel Solaris. In 1976, Theodore Sturgeon wrote that Lem was the most widely read science fiction writer in the world. Lem was the author of the fundamental philosophical work Summa Technologiae, in which he anticipated the creation of virtual reality, artificial intelligence, and also developed the ideas of human autoevolution, the creation of artificial worlds, and many others. Lem's science fiction works explore philosophical themes through speculations on technology, the nature of intelligence, the impossibility of communication with and understanding of alien intelligence, despair about human limitations, and humanity's place in the universe. His essays and philosophical books cover these and many other topics. Translating his works is difficult due to Lem's elaborate neologisms and idiomatic wordplay. The Sejm (the lower house of the Polish Parliament) declared 2021 Stanisław Lem Year.

7. Anna Akhmatova (1889 - 1966)

With an HPI of 76.43, Anna Akhmatova is the 7th most famous Ukrainian Writer. Her biography has been translated into 102 different languages.

Anna Andreyevna Gorenko (23 June [O.S. 11 June] 1889 – 5 March 1966), better known by the pen name Anna Akhmatova, was a Russian and Soviet poet, one of the most significant of the 20th century. She reappeared as a voice of Russian poetry during World War II. She was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1965 and 1966. Akhmatova's work ranges from short lyric poems to intricately structured cycles, such as Requiem (1935–40), her tragic masterpiece about the Stalinist terror. Her style, characterised by its economy and emotional restraint, was strikingly original and distinctive to her contemporaries. The strong and clear leading female voice struck a new chord in Russian poetry. Her writing can be said to fall into two periods – the early work (1912–25) and her later work (from around 1936 until her death), divided by a decade of reduced literary output. Her work was condemned and censored by Stalinist authorities, and she is notable for choosing not to emigrate and remaining in the Soviet Union, acting as witness to the events around her. Her perennial themes include meditations on time and memory, and the difficulties of living and writing in the shadow of Stalinism. Primary sources of information about Akhmatova's life are relatively scant, as war, revolution and the Soviet regime caused much of the written record to be destroyed. For long periods she was in official disfavour and many of those who were close to her died in the aftermath of the revolution. Akhmatova's first husband, Nikolai Gumilev, was executed by the Cheka, and her son Lev Gumilev and her common-law husband Nikolay Punin spent many years in the Gulag, where Punin died.

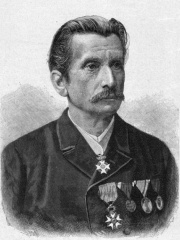

8. Leopold von Sacher-Masoch (1836 - 1895)

With an HPI of 74.47, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch is the 8th most famous Ukrainian Writer. His biography has been translated into 43 different languages.

Leopold Ritter von Sacher-Masoch (German: [ˈleːopɔlt fɔn ˈzaxɐ ˈmaːzɔx]; 27 January 1836 – 9 March 1895) was an Austrian nobleman, writer and journalist, who gained renown for his romantic stories of Galician life. The term masochism is derived from his name, invented by his contemporary, the Austrian psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing. Masoch did not approve of this use of his name. During his lifetime, Sacher-Masoch was well known as a man of letters, in particular a utopian thinker who espoused socialist and humanist ideals in his fiction and non-fiction. Most of his works remain untranslated into English.

9. Joseph Roth (1894 - 1939)

With an HPI of 74.16, Joseph Roth is the 9th most famous Ukrainian Writer. His biography has been translated into 49 different languages.

Moses Joseph Roth (Austrian German: [roːt]; 2 September 1894 – 27 May 1939) was an Austrian journalist and novelist, best known for his family saga Radetzky March (1932), about the decline and fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, his novel of Jewish life Job (1930) and his seminal essay "Juden auf Wanderschaft" (1927; translated into English as The Wandering Jews), a fragmented account of the Jewish migrations from eastern to western Europe in the aftermath of World War I and the Russian Revolution. In the 21st century, publications in English of Radetzky March and of collections of his journalism from Berlin and Paris created a revival of interest in Roth.

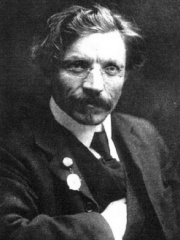

10. Sholem Aleichem (1859 - 1916)

With an HPI of 73.55, Sholem Aleichem is the 10th most famous Ukrainian Writer. His biography has been translated into 48 different languages.

Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich (Russian: Соломон Наумович Рабинович; March 2 [O.S. February 18] 1859 – May 13, 1916), better known under his pen name Sholem Aleichem, was a Yiddish author and playwright who lived in the Russian Empire and in the United States. The 1964 musical Fiddler on the Roof, based on Aleichem's stories about Tevye the Dairyman, was the first commercially successful English-language stage production about Jewish life in Eastern Europe. The Hebrew phrase שלום עליכם (shalom aleichem) literally means "[May] peace [be] upon you!", and is a greeting in traditional Hebrew and Yiddish.

People

Pantheon has 150 people classified as Ukrainian writers born between 1056 and 1990. Of these 150, 23 (15.33%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Ukrainian writers include Svetlana Alexievich, Lina Kostenko, and Vladimir Megre. The most famous deceased Ukrainian writers include Nikolai Gogol, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Taras Shevchenko. As of April 2024, 6 new Ukrainian writers have been added to Pantheon including Natalka Sniadanko, Taras Prokhasko, and Katja Petrowskaja.

Living Ukrainian Writers

Go to all RankingsSvetlana Alexievich

1948 - Present

HPI: 78.14

Lina Kostenko

1930 - Present

HPI: 64.42

Vladimir Megre

1950 - Present

HPI: 58.93

Oksana Zabuzhko

1960 - Present

HPI: 58.48

Emma Andijewska

1931 - Present

HPI: 57.20

Yurii Andrukhovych

1960 - Present

HPI: 55.25

Serhiy Zhadan

1974 - Present

HPI: 54.22

Dmitry Gordon

1967 - Present

HPI: 52.46

Mikhail Gurevich

1959 - Present

HPI: 51.90

Ihor Pavlyuk

1967 - Present

HPI: 47.86

Eugene Vodolazkin

1964 - Present

HPI: 47.33

Sofia Andrukhovych

1982 - Present

HPI: 45.53

Deceased Ukrainian Writers

Go to all RankingsNikolai Gogol

1809 - 1852

HPI: 82.82

Mikhail Bulgakov

1891 - 1940

HPI: 78.73

Taras Shevchenko

1814 - 1861

HPI: 78.66

Joseph Conrad

1857 - 1924

HPI: 78.29

Stanisław Lem

1921 - 2006

HPI: 77.56

Anna Akhmatova

1889 - 1966

HPI: 76.43

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch

1836 - 1895

HPI: 74.47

Joseph Roth

1894 - 1939

HPI: 74.16

Sholem Aleichem

1859 - 1916

HPI: 73.55

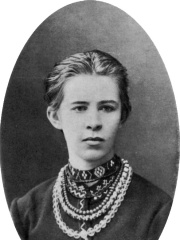

Lesya Ukrainka

1871 - 1913

HPI: 72.77

Isaac Babel

1894 - 1940

HPI: 72.61

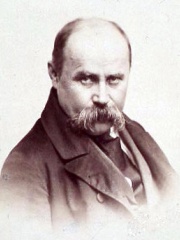

Ivan Franko

1856 - 1916

HPI: 72.57

Newly Added Ukrainian Writers (2025)

Go to all RankingsNatalka Sniadanko

1973 - Present

HPI: 43.86

Taras Prokhasko

1968 - Present

HPI: 43.44

Katja Petrowskaja

1970 - Present

HPI: 43.41

Tamara Duda

1976 - Present

HPI: 42.62

Stanislav Aseyev

1989 - Present

HPI: 39.61

Hanna Yablonska

1981 - 2011

HPI: 37.22

Overlapping Lives

Which Writers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Writers since 1700.