The Most Famous

WRITERS from United States

This page contains a list of the greatest American Writers. The pantheon dataset contains 7,302 Writers, 1,301 of which were born in United States. This makes United States the birth place of the most number of Writers.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary American Writers of all time. This list of famous American Writers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of American Writers.

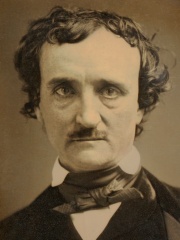

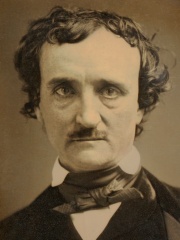

1. Edgar Allan Poe (1809 - 1849)

With an HPI of 90.35, Edgar Allan Poe is the most famous American Writer. His biography has been translated into 148 different languages on wikipedia.

Edgar Allan Poe (né Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely regarded as one of the central figures of Romanticism and Gothic fiction in the United States and of early American literature. Poe was one of the country's first successful practitioners of the short story, and is generally considered to be the inventor of the detective fiction genre. In addition, he is credited with contributing significantly to the emergence of science fiction. He is the first well-known American writer to earn a living exclusively through writing, which resulted in a financially difficult life and career. Poe was born in Boston. He was the second child of actors David and Elizabeth "Eliza" Poe. His father abandoned the family in 1810, and when Eliza died the following year, Poe was taken in by John and Frances Allan of Richmond, Virginia. They never formally adopted him, but he lived with them well into young adulthood. Poe attended the University of Virginia but left after only a year due to a lack of money. He frequently quarreled with John Allan over the funds needed to continue his education as well as his gambling debts. In 1827, having enlisted in the United States Army under the assumed name of Edgar A. Perry, he published his first collection, Tamerlane and Other Poems, which was credited only to "a Bostonian". Poe and Allan reached a temporary rapprochement after the death of Allan's wife, Frances, in 1829. However, Poe later failed as an officer cadet at West Point, declared his intention to become a writer, primarily of poems, and parted ways with Allan. Poe switched his focus to prose and spent the next several years working for literary journals and periodicals, becoming known for his own style of literary criticism. His work forced him to move between several cities, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City. In 1836, when he was 27, he married his 13-year-old cousin, Virginia Clemm. She died of tuberculosis in 1847. In January 1845, he published his poem "The Raven" to instant success. He planned for years to produce his own journal, The Penn, later renamed The Stylus – but before it began publishing, Poe died in Baltimore in 1849, aged 40, under mysterious circumstances. The cause of his death remains unknown and has been attributed to many causes, including disease, alcoholism, substance abuse, and suicide. Poe's works influenced the development of literature throughout the world and even impacted such specialized fields as cosmology and cryptography. Since his death, he and his writings have appeared throughout popular culture in such fields as art, photography, literary allusions, music, motion pictures, and television. Several of his homes are dedicated museums. In addition, The Mystery Writers of America presents an annual Edgar Award for distinguished work in the mystery genre.

2. T. S. Eliot (1888 - 1965)

With an HPI of 87.25, T. S. Eliot is the 2nd most famous American Writer. His biography has been translated into 112 different languages.

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 1888 – 4 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright. He was a leading figure in English-language Modernist poetry where he reinvigorated the art through his use of language, writing style, and verse structure. He is also noted for his critical essays, which often re-evaluated long-held cultural beliefs. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, to a prominent Boston Brahmin family, he moved to England in 1914 at the age of 25 and went on to settle, work, and marry there. He became a British subject in 1927 at the age of 39 and renounced his American citizenship. Eliot first attracted widespread attention for "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" (1915), which, at the time of its publication, was considered outlandish. It was followed by The Waste Land (1922), "The Hollow Men" (1925), "Ash Wednesday" (1930), and Four Quartets (1943). He wrote seven plays, including Murder in the Cathedral (1935) and The Cocktail Party (1949). He was awarded the 1948 Nobel Prize in Literature "for his outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry".

3. Emily Dickinson (1830 - 1886)

With an HPI of 85.12, Emily Dickinson is the 3rd most famous American Writer. Her biography has been translated into 99 different languages.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, into a prominent family with strong ties to its community. After studying at the Amherst Academy for seven years in her youth, she briefly attended the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary before returning to her family's home in Amherst. Evidence indicates that Dickinson spent much of her life in relative isolation. Regarded as eccentric by local residents, she frequently wore white clothing and was noted for her limited interactions with visitors, and later in life, for rarely leaving her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most of her friendships were based entirely upon correspondence. Although Dickinson was a prolific writer, her only publications during her lifetime were one letter and 10 of her nearly 1,800 poems. The poems published then were usually edited significantly to fit conventional poetic rules. Her poems were unique for her era; they contain short lines, typically lack titles, and often use slant rhyme as well as unconventional capitalization and punctuation. Many of her poems deal with themes of death and immortality (two recurring topics in letters to her friends), aesthetics, society, nature, and spirituality. Although Dickinson's acquaintances were most likely aware of her writing, it was not until after she died in 1886—when Lavinia, Dickinson's younger sister, discovered her cache of poems—that her work became public. Her first published collection of poetry was made in 1890 by her personal acquaintances Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd, though they heavily edited the content. A complete collection of her poetry first became available in 1955 when scholar Thomas H. Johnson published The Poems of Emily Dickinson. At least eleven of Dickinson's poems were dedicated to her sister-in-law Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson, and all the dedications were later obliterated, presumably by Todd. This censorship serves to obscure the nature of Emily and Susan's relationship, which many scholars have interpreted as romantic.

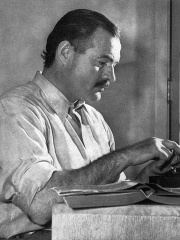

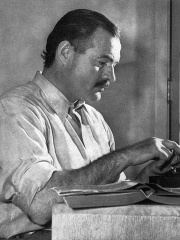

4. Ernest Hemingway (1899 - 1961)

With an HPI of 84.99, Ernest Hemingway is the 4th most famous American Writer. His biography has been translated into 151 different languages.

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( HEM-ing-way; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized for his adventurous lifestyle and outspoken, blunt public image. Some of his seven novels, six short-story collections and two non-fiction works have become classics of American literature, and he was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature. Hemingway was raised in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. After high school, he spent six months as a reporter for The Kansas City Star before enlisting in the Red Cross. He served as an ambulance driver on the Italian Front in World War I and was seriously wounded by shrapnel in 1918. In 1921, Hemingway moved to Paris, where he worked as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star and was influenced by the modernist writers and artists of the "Lost Generation" expatriate community. His debut novel, The Sun Also Rises, was published in 1926. In 1928, Hemingway returned to the U.S., where he settled in Key West, Florida. His experiences during the war supplied material for his 1929 novel A Farewell to Arms. In 1937, Hemingway went to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War, which formed the basis for his 1940 novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, written in Havana, Cuba. During World War II, Hemingway was present with Allied troops as a journalist at the Normandy landings and the liberation of Paris. In 1952, his novel The Old Man and the Sea was published to considerable acclaim, and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. On a 1954 trip to Africa, Hemingway was seriously injured in two successive plane crashes, leaving him in pain and ill health for much of the rest of his life. He died of suicide at his house in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961.

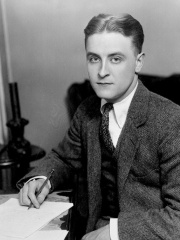

5. F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896 - 1940)

With an HPI of 84.65, F. Scott Fitzgerald is the 5th most famous American Writer. His biography has been translated into 83 different languages.

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940), widely known as F. Scott Fitzgerald or simply Scott Fitzgerald, was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age, a term that he popularized in his short story collection Tales of the Jazz Age. He published four novels, four story collections, and 164 short stories. He achieved transient success and fortune in the 1920s, but did not receive critical acclaim until after his death. He is now widely regarded as one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century. Fitzgerald was born into a middle-class family in Saint Paul, Minnesota, but he was raised primarily in New York state. He attended Princeton University where he befriended future literary critic Edmund Wilson. He had a failed romantic relationship with Chicago socialite Ginevra King and dropped out of Princeton in 1917 to join the Army during World War I. While stationed in Alabama, he met Zelda Sayre, a Southern debutante who belonged to Montgomery's exclusive country-club set. She initially rejected Fitzgerald's marriage proposal due to his lack of financial prospects, but she agreed to marry him after he published the commercially successful This Side of Paradise (1920). The novel became a cultural sensation and cemented his reputation as one of the eminent writers of the decade. His second novel The Beautiful and Damned (1922) propelled Fitzgerald further into the cultural elite. To maintain his affluent lifestyle, he wrote numerous stories for popular magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, Collier's Weekly, and Esquire. He frequented Europe during this period, where he befriended modernist writers and artists of the "Lost Generation" expatriate community, including Ernest Hemingway. His third novel The Great Gatsby (1925) received generally favorable reviews but was a commercial failure, selling fewer than 23,000 copies in its first year. Despite its lackluster debut, The Great Gatsby is hailed by some literary critics as the "Great American Novel". Fitzgerald completed his last completed novel Tender Is the Night (1934) following the deterioration of his wife's mental health and her placement in a mental institution for schizophrenia. Fitzgerald struggled financially because of the declining popularity of his works during the Great Depression. He then moved to Hollywood where he embarked on an unsuccessful career as a screenwriter. While living in Hollywood, he cohabited with columnist Sheilah Graham, his final companion before his death. He had long struggled with alcoholism, and he attained sobriety only to die of a heart attack in 1940 at age 44. His friend Edmund Wilson edited and published the unfinished The Last Tycoon (1941). Wilson described Fitzgerald's style: "romantic, but also cynical; he is bitter as well as ecstatic; astringent as well as lyrical. He casts himself in the role of playboy, yet at the playboy he incessantly mocks. He is vain, a little malicious, of quick intelligence and wit, and has the Irish gift for turning language into something iridescent and surprising."

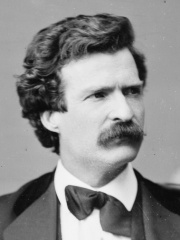

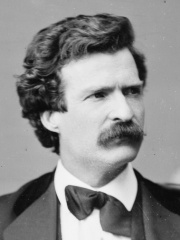

6. Mark Twain (1835 - 1910)

With an HPI of 83.94, Mark Twain is the 6th most famous American Writer. His biography has been translated into 157 different languages.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced", with William Faulkner calling him "the father of American literature". Twain's novels include The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), with the latter often called the "Great American Novel". He also wrote A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889) and Pudd'nhead Wilson (1894) and cowrote The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873) with Charles Dudley Warner. The novelist Ernest Hemingway claimed that "All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn." Twain was raised in Hannibal, Missouri, which later provided the setting for both Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. He served an apprenticeship with a printer early in his career, and then worked as a typesetter, contributing articles to his older brother Orion Clemens' newspaper. Twain then became a riverboat pilot on the Mississippi River, which provided him the material for Life on the Mississippi (1883). Soon after, Twain headed west to join Orion in Nevada. He referred humorously to his lack of success at mining, turning to journalism for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. Twain first achieved success as a writer with the humorous story "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," which was published in 1865; it was based on a story that he heard at the Angels Hotel in Angels Camp, California, where Twain had spent some time while he was working as a miner. The short story brought Twain international attention. He wrote both fiction and non-fiction. As his fame grew, Twain became a much sought-after speaker. His wit and satire, both in prose and in speech, earned praise from critics and peers, and Twain was a friend to presidents, artists, industrialists, and European royalty. Although Twain initially spoke out in favor of American interests in the Hawaiian Islands, he later reversed his position, going on to become vice president of the American Anti-Imperialist League from 1901 until his death in 1910, coming out strongly against the Philippine–American War and American colonialism. Twain published a satirical pamphlet, "King Leopold's Soliloquy", in 1905 about Belgian atrocities in the Congo Free State. Twain earned a great deal of money from his writing and lectures, but invested in ventures that lost most of it, such as the Paige Compositor, a mechanical typesetter that failed because of its complexity and imprecision. He filed for bankruptcy after these financial setbacks, but in time overcame his financial troubles with the help of Standard Oil executive Henry Huttleston Rogers, who helped Twain manage his finances and copyrights. Twain eventually paid all his creditors in full, even though his declaration of bankruptcy meant he was not required to do so. One hundred years after his death, the first volume of his autobiography was published. Twain was born shortly after an appearance of Halley's Comet and predicted that his death would accompany it as well, writing in 1909: "I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835; it's coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It would be a great disappointment in my life if I don't. The Almighty has said, no doubt: 'Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.'" He died of a heart attack the day after the comet was at its closest to the Sun.

7. Robert Frost (1874 - 1963)

With an HPI of 83.18, Robert Frost is the 7th most famous American Writer. His biography has been translated into 81 different languages.

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 – January 29, 1963) was an American poet. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech, Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New England in the early 20th century, using them to examine complex social and philosophical themes. Frequently honored during his lifetime, Frost is the only poet to receive four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. He became one of America's rare "public literary figures, almost an artistic institution". Appointed United States Poet Laureate in 1958, he also received the Congressional Gold Medal in 1960, and in 1961 was named poet laureate of Vermont. Randall Jarrell wrote: "Robert Frost, along with Stevens and Eliot, seems to me the greatest of the American poets of this century. Frost's virtues are extraordinary. No other living poet has written so well about the actions of ordinary men; his wonderful dramatic monologues or dramatic scenes come out of a knowledge of people that few poets have had, and they are written in a verse that uses, sometimes with absolute mastery, the rhythms of actual speech". In his 1939 essay "The Figure a Poem Makes", Frost explains his poetics:No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader. For me the initial delight is in the surprise of remembering something I didn't know I knew...[Poetry] must be a revelation, or a series of revelations, for the poet as for the reader. For it to be that there must have been the greatest freedom of the material to move about in it and to establish relations in it regardless of time and space, previous relation, and everything but affinity.

8. Toni Morrison (1931 - 2019)

With an HPI of 82.91, Toni Morrison is the 8th most famous American Writer. Her biography has been translated into 108 different languages.

Chloe Anthony Wofford "Toni" Morrison (born Chloe Ardelia Wofford; February 18, 1931 – August 5, 2019) was an American novelist and editor. She was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993. Her first novel, The Bluest Eye, was published in 1970. The critically acclaimed Song of Solomon (1977) brought her national attention and won the National Book Critics Circle Award. In 1988, Morrison won the Pulitzer Prize for Beloved (1987). Born and raised in Lorain, Ohio, Morrison graduated from Howard University in 1953 with a B.A. in English. Morrison earned a master's degree in American Literature from Cornell University in 1955. In 1957 she returned to Howard University, was married, and had two children before divorcing in 1964. Morrison became the first Black female editor for fiction at Random House in New York City in the late 1960s. She developed her own reputation as an author in the 1970s and '80s. Her novel Beloved was made into a film in 1998. Morrison's works are praised for addressing the harsh consequences of racism in the United States and the Black American experience. The National Endowment for the Humanities selected Morrison for the Jefferson Lecture, the U.S. federal government's highest honor for achievement in the humanities, in 1996. She was honored with the National Book Foundation's Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters the same year. President Barack Obama presented her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom on May 29, 2012. She received the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction in 2016. Morrison was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 2020.

9. George R. R. Martin (b. 1948)

With an HPI of 82.87, George R. R. Martin is the 9th most famous American Writer. His biography has been translated into 91 different languages.

George Raymond Richard Martin (born George Raymond Martin; September 20, 1948) also known by the initials G.R.R.M. is an American author, screenwriter, and television producer. He is best known as the author of the series of epic fantasy novels A Song of Ice and Fire, which were adapted into the Primetime Emmy Award–winning television series Game of Thrones (2011–2019) and its prequel series House of the Dragon (2022–present). He also helped create the Wild Cards anthology series and contributed worldbuilding for the video game Elden Ring (2022). In 2005, Lev Grossman of Time called Martin "the American Tolkien", and in 2011, he was included on the annual Time 100 list of the most influential people in the world. He is a longtime resident of Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he helped fund Meow Wolf and owns the Jean Cocteau Cinema. The city commemorates March 29 as George R. R. Martin Day.

10. Kurt Vonnegut (1922 - 2007)

With an HPI of 82.15, Kurt Vonnegut is the 10th most famous American Writer. His biography has been translated into 83 different languages.

Kurt Vonnegut ( VON-ə-gət; November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007) was an American author known for his satirical and darkly humorous novels. His published work includes fourteen novels, three short-story collections, five plays, and five nonfiction works over fifty years; further works have been published since his death. Born and raised in Indianapolis, Vonnegut attended Cornell University, but withdrew in January 1943 and enlisted in the U.S. Army. As part of his training, he studied mechanical engineering at the Carnegie Institute of Technology and the University of Tennessee. He was then deployed to Europe to fight in World War II and was captured by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge. He was interned in Dresden, where he survived the Allied bombing of the city in a meat locker of the slaughterhouse where he was imprisoned. After the war, he married Jane Marie Cox. He and his wife both attended the University of Chicago while he worked as a night reporter for the City News Bureau. Vonnegut published his first novel, Player Piano, in 1952. It received favorable reviews yet sold poorly. In the nearly 20 years that followed, several well-regarded novels were published, including The Sirens of Titan (1959) and Cat's Cradle (1963), both of which were nominated for the Hugo Award for best science fiction novel of the year. His short-story collection, Welcome to the Monkey House, was published in 1968. Vonnegut's breakthrough was his commercially and critically successful sixth novel, Slaughterhouse-Five (1969). Its anti-war sentiment resonated with its readers amid the Vietnam War, and its reviews were generally positive. It rose to the top of The New York Times Best Seller list and made Vonnegut famous. Later in his career, Vonnegut published autobiographical essays and short-story collections such as Fates Worse Than Death (1991) and A Man Without a Country (2005). He has been hailed for his darkly humorous commentary on American society. His son Mark published a compilation of his work, Armageddon in Retrospect, in 2008. In 2017, Seven Stories Press published Complete Stories, a collection of Vonnegut's short fiction.

People

Pantheon has 1,301 people classified as American writers born between 1663 and 2000. Of these 1,301, 613 (47.12%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living American writers include George R. R. Martin, Stephen King, and David Woodard. The most famous deceased American writers include Edgar Allan Poe, T. S. Eliot, and Emily Dickinson. As of April 2024, 75 new American writers have been added to Pantheon including Norah Vincent, Martha Wells, and Rebecca Yarros.

Living American Writers

Go to all RankingsGeorge R. R. Martin

1948 - Present

HPI: 82.87

Stephen King

1947 - Present

HPI: 81.49

David Woodard

1964 - Present

HPI: 78.20

J. D. Vance

1984 - Present

HPI: 74.96

Ivanka Trump

1981 - Present

HPI: 74.61

Coen brothers

HPI: 74.48

Dan Brown

1964 - Present

HPI: 73.29

Richard Bach

1936 - Present

HPI: 72.37

Thomas Friedman

1953 - Present

HPI: 70.66

John Irving

1942 - Present

HPI: 70.53

Marilyn vos Savant

1946 - Present

HPI: 69.58

Daniel Goleman

1946 - Present

HPI: 69.20

Deceased American Writers

Go to all RankingsEdgar Allan Poe

1809 - 1849

HPI: 90.35

T. S. Eliot

1888 - 1965

HPI: 87.25

Emily Dickinson

1830 - 1886

HPI: 85.12

Ernest Hemingway

1899 - 1961

HPI: 84.99

F. Scott Fitzgerald

1896 - 1940

HPI: 84.65

Mark Twain

1835 - 1910

HPI: 83.94

Robert Frost

1874 - 1963

HPI: 83.18

Toni Morrison

1931 - 2019

HPI: 82.91

Kurt Vonnegut

1922 - 2007

HPI: 82.15

Louisa May Alcott

1832 - 1888

HPI: 81.95

Ursula K. Le Guin

1929 - 2018

HPI: 81.89

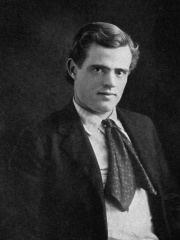

Jack London

1876 - 1916

HPI: 81.73

Newly Added American Writers (2025)

Go to all RankingsNorah Vincent

1968 - 2022

HPI: 53.60

Martha Wells

1964 - Present

HPI: 50.80

Rebecca Yarros

1981 - Present

HPI: 48.98

Hazel Brugger

1993 - Present

HPI: 48.40

Julie Otsuka

1962 - Present

HPI: 47.73

Jeannette Walls

1960 - Present

HPI: 47.17

Adam Curry

1964 - Present

HPI: 46.43

Peter V. Brett

1973 - Present

HPI: 46.36

Marc Laidlaw

1960 - Present

HPI: 46.23

Gonzalo Lira

1968 - 2024

HPI: 45.76

Jeff Abbott

1963 - Present

HPI: 45.48

Jeffrey Goldberg

1965 - Present

HPI: 45.43

Overlapping Lives

Which Writers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Writers since 1700.