The Most Famous

RELIGIOUS FIGURES from United Kingdom

This page contains a list of the greatest British Religious Figures. The pantheon dataset contains 3,187 Religious Figures, 122 of which were born in United Kingdom. This makes United Kingdom the birth place of the 6th most number of Religious Figures behind Germany, and United States.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary British Religious Figures of all time. This list of famous British Religious Figures is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of British Religious Figures.

1. Saint Patrick (385 - 461)

With an HPI of 77.66, Saint Patrick is the most famous British Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 69 different languages on wikipedia.

Saint Patrick (Latin: Pātricius; Irish: Pádraig Irish pronunciation: [ˈpˠɑːɾˠɪɟ] or Irish pronunciation: [ˈpˠaːd̪ˠɾˠəɟ]; Welsh: Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints being Brigid of Kildare and Columba. He is also the patron saint of Nigeria. Patrick was never formally canonised by the Catholic Church, having lived before the current laws were established for such matters. He is venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church, the Lutheran Church, the Church of Ireland (part of the Anglican Communion), and in the Eastern Orthodox Church, where he is regarded as equal-to-the-apostles and Enlightener of Ireland. The dates of Patrick's life cannot be fixed with certainty, but there is general agreement that he was active as a missionary in Ireland during the fifth century. A recent biography on Patrick shows a late fourth-century date for the saint is possible. According to tradition dating from the early Middle Ages, Patrick was the first bishop of Armagh and Primate of Ireland, and is credited with bringing Christianity to Ireland (despite evidence of some earlier Christian presence on the island), and converting Ireland from paganism in the process. In Patrick's autobiographical Confessio, he writes that when he was about sixteen, he was captured by Irish pirates from his home in Britain and taken as a slave to Ireland. He writes that he lived there for six years as an animal herder before escaping and returning to his family. After becoming a cleric, he returned to spread Christianity in northern and western Ireland. In later life, he served as a bishop, but little is known about where he worked. By the seventh century, he had already come to be revered as the patron saint of Ireland. Saint Patrick's Day, considered his feast day, is observed on 17 March, the supposed date of his death. It is celebrated in Ireland and among the Irish diaspora as a religious and cultural holiday. In the Catholic Church in Ireland, it is both a solemnity and a holy day of obligation.

2. Saint Boniface (680 - 754)

With an HPI of 77.14, Saint Boniface is the 2nd most famous British Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 48 different languages.

Boniface (born Wynfreth; c. 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of Francia during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of the church in Germany and was made Archbishop of Mainz by Pope Gregory III. He was martyred in Frisia in 754, along with 52 others, and his remains were returned to Fulda, where they rest in a sarcophagus which remains a site of Christian pilgrimage. Boniface's life and death as well as his work became widely known, there being a wealth of material available – a number of vitae, especially the near-contemporary Vita Bonifatii auctore Willibaldi, legal documents, possibly some sermons, and above all his correspondence. He is venerated as a saint in the Christian church and became the patron saint of Germania, known as the "Apostle to the Germans". Norman Cantor notes the three roles Boniface played that made him "one of the truly outstanding creators of the first Europe, as the apostle of Germania, the reformer of the Frankish Church, and the chief fomentor of the alliance between the papacy and the Carolingian family." Through his efforts to reorganize and regulate the church of the Franks, he helped shape the Latin Church in Europe, and many of the dioceses he proposed remain today. After his martyrdom, he was quickly hailed as a saint in Fulda and other areas in Germania and in England. He is still venerated strongly today by Catholics in Germany and throughout the German diaspora. Boniface is celebrated as a missionary; he is regarded as a unifier of Europe, and he is regarded by German Roman Catholics as a national figure. In 2019 Devon County Council, with the support of the Anglican Diocese of Exeter, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Plymouth, and local Devon leaders of the Orthodox, Methodist, and Congregational churches, officially recognised St Boniface as the Patron Saint of Devon.

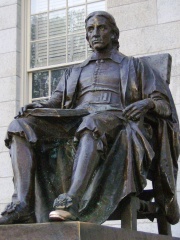

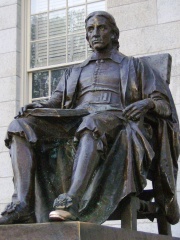

3. John Harvard (1607 - 1638)

With an HPI of 77.02, John Harvard is the 3rd most famous British Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 34 different languages.

John Harvard (1607–1638) was an English Puritan minister in colonial New England whose deathbed bequest to the "schoale or colledge" founded two years earlier by the Massachusetts Bay Colony was so gratefully received that the colony consequently ordered "that the Colledge agreed upon formerly to be built at Cambridge shalbee called Harvard Colledge". Harvard was born in Southwark, England, and earned bachelor's and master's degrees from Emmanuel College, Cambridge. In 1637 he emigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony – one of the Thirteen Colonies of British America – where he became a teaching elder and assistant preacher of the First Church in Charlestown. Harvard died of tuberculosis in 1638, leaving a large sum of money and his 400-volume scholar's library to the colony's new school, which the colony then voted to name in his honor. Harvard University considers him the most honored of its founders—those whose efforts and contributions in its early days "ensure[d] its permanence"—and a statue in his honor is a prominent feature of Harvard Yard.

4. Saint Ursula (400 - 383)

With an HPI of 75.60, Saint Ursula is the 4th most famous British Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 37 different languages.

Ursula (Latin for 'little she-bear') was a Romano-British virgin and martyr possibly of royal origin. She is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church and the Anglican Communion. Her feast day in the pre-1970 General Roman Calendar and in some regional calendars of the ordinary form of the Roman Rite is 21 October.

5. Saint Walpurga (710 - 779)

With an HPI of 74.05, Saint Walpurga is the 5th most famous British Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 32 different languages.

Walpurga or Walburga (Old English: Wealdburg; Latin: Valpurga, Walpurga, Walpurgis; Swedish: Valborg; c. 710 – 25 February 777 or 779) was an Anglo-Saxon missionary to the Frankish Empire. She was canonized on 1 May c. 870 by Pope Adrian II. Saint Walpurgis Night (or "Sankt Walpurgisnacht") is the name for the eve of her feast day in the Medieval period, which coincided with May Day; her feast is no longer celebrated on that day, but the name is still used for May Eve.

6. Alcuin (735 - 804)

With an HPI of 73.89, Alcuin is the 6th most famous British Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 53 different languages.

Alcuin of York (; Latin: Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; c. 735 – 19 May 804), also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin, was an Anglo-Latin scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student of Archbishop Ecgbert at York. At the invitation of Charlemagne, he became a leading scholar and teacher at the Carolingian court, where he remained a figure in the 780s and 790s. Before that, he was also a court chancellor in Aachen. "The most learned man anywhere to be found", according to Einhard's Life of Charlemagne (c. 817–833), he is considered among the most important intellectual architects of the Carolingian Renaissance. Among his pupils were many of the dominant intellectuals of the Carolingian era. Alcuin wrote many theological and dogmatic treatises, as well as a few grammatical works and a number of poems. In 796, he was made abbot of Marmoutier Abbey, in Tours, where he worked on perfecting the Carolingian minuscule script. He remained there until his death.

7. William Laud (1573 - 1645)

With an HPI of 73.32, William Laud is the 7th most famous British Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 32 different languages.

William Laud (7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms; he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 and executed towards the end of the First English Civil War in January 1645. Laud believed in episcopalianism, or rule by bishops. "Laudianism" was a reform movement that emphasised liturgical ceremony and clerical hierarchy, enforcing uniformity within the Church of England, as outlined by Charles. Its often highly ritualistic aspects prefigure what are now known as high church views. In theology, Laud was accused of Arminianism, favouring doctrines of the historic church prior to the Reformation and defending the continuity of the English Church with the primitive and medieval church, and opposing Calvinism. On all three grounds, he was regarded by Puritan clerics and laymen as a formidable and dangerous opponent. His use of the Star Chamber to persecute opponents such as William Prynne made him deeply unpopular.

8. John Wesley (1703 - 1791)

With an HPI of 71.96, John Wesley is the 8th most famous British Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 55 different languages.

John Wesley ( WESS-lee; 28 June [O.S. 17 June] 1703 – 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, theologian, and evangelist who was a principal leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies he founded became the dominant form of the independent Methodist movement that continues to this day. Educated at Charterhouse and Christ Church, Oxford, Wesley was elected a fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford, in 1726 and ordained as an Anglican priest two years later. At Oxford, he led the "Holy Club", a society formed for the purpose of the study and the pursuit of a devout Christian life. After an unsuccessful two-year ministry in Savannah, Georgia, he returned to London and joined a religious society led by Moravian Christians. On 24 May 1738, he experienced what has come to be called his evangelical conversion. He left the Moravians and began his own ministry. A key step in the development of Wesley's ministry was to travel widely and preach outdoors, embracing Arminian doctrines. Moving across Great Britain and Ireland, he helped form and organise small Christian groups that developed intensive and personal accountability, discipleship, and religious instruction. He appointed itinerant, unordained evangelists—both women and men—to care for these groups of people. Under Wesley's direction, Methodists became leaders in many social issues of the day, including the abolition of slavery and support for women preachers. Although he was not a systematic theologian, Wesley argued against Calvinism and for the notion of Christian perfection, which he cited as the reason that he felt God "raised up" Methodists into existence. His evangelicalism, firmly grounded in sacramental theology, maintained that means of grace played a role in sanctification of the believer; however, he taught that it was by faith a believer was transformed into the likeness of Christ. He held that, in this life, Christians could achieve a state where the love of God "reigned supreme in their hearts", giving them not only outward but inward holiness. Wesley's teachings, collectively known as Wesleyan theology, continue to inform the doctrine of Methodist churches. In his early ministry years, Wesley was barred from preaching in many parish churches and the Methodists were persecuted; he later became widely respected, and by the end of his life, was described as "the best-loved man in England".

9. Thomas Becket (1119 - 1170)

With an HPI of 71.64, Thomas Becket is the 9th most famous British Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 59 different languages.

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English cleric and statesman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his death in 1170. He is known for his conflict with King Henry II over the rights and privileges of the Church and was murdered by followers of the king in Canterbury Cathedral. He was canonised by Pope Alexander III two years after his death. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion.

10. Pope Adrian IV (1100 - 1159)

With an HPI of 71.56, Pope Adrian IV is the 10th most famous British Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 77 different languages.

Pope Adrian (or Hadrian) IV (Latin: Hadrianus IV; born Nicholas Breakspear (or Brekespear); c. 1100 – 1 September 1159) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 4 December 1154 until his death in 1159. He is the only pope to have been born in England and the first pope from the Anglosphere. Adrian was born in Hertfordshire, England, but little is known of his early life. Although he does not appear to have received a great degree of schooling, while still a youth he travelled to the south of France where he was schooled in Arles, studying law. He then travelled to Avignon, where he joined the Abbey of Saint-Ruf. There he became a canon regular and was eventually appointed abbot. He travelled to Rome several times, where he appears to have caught the attention of Pope Eugene III, and was sent on a mission to Catalonia where the Reconquista was attempting to reclaim land from the Muslim Al-Andalus. Around this time his abbey complained to Eugene that Breakspear was too heavy a disciplinarian, and in order to make use of him as a papal legate as well as to pacify his monks, he was appointed Bishop of Albano some time around 1149. As bishop, Breakspear was soon sent on another diplomatic mission, this time to Scandinavia. At the outset of the Civil war era in Norway, Breakspear reorganised the Church in Norway and then moved on to Sweden. Here, he was very much acclaimed by the people, and when he left, chroniclers called him a saint. Breakspear returned to Rome in 1154; Eugene's successor Pope Anastasius IV had died only a few weeks previously. For reasons now unknown, but possibly at his predecessor's request, Breakspear was elected next pope by the cardinals. He was unable to complete his coronation service, however, because of the parlous state of politics in Rome, which also at the time was considered a den for 'heresy' and republicanism. Adrian decisively restored the papal authority there, but his other major policy issue—relations with the newly crowned Holy Roman emperor, Frederick I—started off badly and got progressively worse. Each party, as a result of a particular aggravating incident, found something to condemn the other for. As a result, Adrian entered into an alliance with the Byzantine emperor, Manuel I Komnenos, who was keen to re-assert his authority in the south of Italy, but was unable to do so due to the Norman kings' occupation of the region, now under William I of Sicily. Adrian's alliance with the Byzantine emperor came to nothing, as William decisively defeated Manuel and forced Adrian to come to terms at the Treaty of Benevento. This alienated Emperor Frederick even more, as he saw it as a repudiation of their existing treaty. Relations soured further when Frederick laid claim to a large swathe of territory in northern Italy. Adrian's relations with his country of birth, however, seem to have remained generally good. Certainly, he showered St Albans Abbey with privileges, and he appears to have forwarded King Henry II's policies where he could. Most famously, in 1158 Adrian is supposed to have granted Henry the papal bull Laudabiliter, which is thought to have authorised Henry to invade Ireland. Henry did not do so, however, for another 14 years, and scholars are uncertain whether the bull ever existed. Following Adrian's death at Anagni, there was uncertainty as to who to succeed him, with both pro- and anti-imperial cardinals voting for different candidates. Although Pope Alexander III officially took over, the subsequent election of an antipope led to a 22-year-long schism. Scholars have debated Adrian's pontificate widely. Much of a positive nature—his building programme and reorganisation of papal finances, for example—has been identified, particularly in the context of such a short reign. He was also up against powerful forces out of his control, which, while he never overcame them, he managed effectively.

People

Pantheon has 122 people classified as British religious figures born between 300 and 1991. Of these 122, 6 (4.92%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living British religious figures include Paul Gallagher, Arthur Roche, and Justin Welby. The most famous deceased British religious figures include Saint Patrick, Saint Boniface, and John Harvard.

Living British Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsPaul Gallagher

1954 - Present

HPI: 62.15

Arthur Roche

1950 - Present

HPI: 58.99

Justin Welby

1956 - Present

HPI: 57.76

Vincent Nichols

1945 - Present

HPI: 56.41

Rowan Williams

1950 - Present

HPI: 56.13

Ajahn Brahm

1951 - Present

HPI: 55.19

Deceased British Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsSaint Patrick

385 - 461

HPI: 77.66

Saint Boniface

680 - 754

HPI: 77.14

John Harvard

1607 - 1638

HPI: 77.02

Saint Ursula

400 - 383

HPI: 75.60

Saint Walpurga

710 - 779

HPI: 74.05

Alcuin

735 - 804

HPI: 73.89

William Laud

1573 - 1645

HPI: 73.32

John Wesley

1703 - 1791

HPI: 71.96

Thomas Becket

1119 - 1170

HPI: 71.64

Pope Adrian IV

1100 - 1159

HPI: 71.56

John Knox

1514 - 1572

HPI: 71.26

Edward the Confessor

1003 - 1066

HPI: 71.18

Overlapping Lives

Which Religious Figures were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Religious Figures since 1700.