The Most Famous

RELIGIOUS FIGURES from Germany

This page contains a list of the greatest German Religious Figures. The pantheon dataset contains 3,187 Religious Figures, 134 of which were born in Germany. This makes Germany the birth place of the 4th most number of Religious Figures behind France, and Türkiye.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary German Religious Figures of all time. This list of famous German Religious Figures is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of German Religious Figures.

1. Pope Benedict XVI (1927 - 2022)

With an HPI of 93.90, Pope Benedict XVI is the most famous German Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 149 different languages on wikipedia.

Pope Benedict XVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of Vatican City from 2005 until his resignation in 2013. Following his resignation, he chose to be known as "pope emeritus", a title he held until his death on 31 December 2022. Ordained as a priest in 1951 in his native Bavaria, Ratzinger embarked on an academic career and established himself as a highly regarded theologian by the late 1950s. He was appointed a full professor in 1958 when aged 31. After a long career as a professor of theology at several German universities, he was appointed Archbishop of Munich and Freising and created a cardinal by Pope Paul VI in 1977, an unusual promotion for someone with little pastoral experience. In 1981, he was appointed Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, one of the most important dicasteries of the Roman Curia. In 2002, he also became Dean of the College of Cardinals. Before becoming pope, he had been "a major figure on the Vatican stage for a quarter of a century"; he had had an influence "second to none when it came to setting church priorities and directions" as one of John Paul II's closest confidants. Following the death of John Paul II on 2 April 2005, a conclave elected Ratzinger as his successor on 19 April; he chose Benedict XVI as his papal name in honour of Benedict XV and Benedict of Nursia. Benedict's writings were prolific and generally defended traditional Catholic doctrine, values, and liturgy. He was originally a liberal theologian but adopted conservative views after 1968. During his papacy, Benedict advocated a return to fundamental Christian values to counter the increased secularisation of many Western countries. He viewed relativism's denial of objective truth, and the denial of moral truths in particular, as the central problem of the 21st century. Benedict also revived several traditions and permitted greater use of the Tridentine Mass. He strengthened the relationship between the Catholic Church and art, promoted the use of Latin, and reintroduced traditional papal vestments, for which reason he was called "the pope of aesthetics". He also established personal ordinariates for former Anglicans and Methodists joining the Catholic Church. Benedict's handling of sexual abuse cases within the Catholic Church and opposition to usage of condoms in areas of high HIV transmission was criticized by public health officials, anti-AIDS activists, and victims' rights organizations. Citing health reasons due to his advanced age, Benedict resigned as pope on 28 February 2013. He became the first pope to resign from office since Gregory XII in 1415, and the first without external pressure since Celestine V in 1294. He subsequently moved into the newly renovated Mater Ecclesiae Monastery in Vatican City for his retirement. The 2013 conclave elected Francis as his successor on 13 March. In addition to his native German language, Benedict had some proficiency in French, Italian, English, and Spanish. He also knew Portuguese, Latin, Biblical Hebrew, and Biblical Greek. He was a member of several social science academies, such as the French Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques.

2. Martin Luther (1483 - 1546)

With an HPI of 92.77, Martin Luther is the 2nd most famous German Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 187 different languages.

Martin Luther ( LOO-thər; German: [ˈmaʁtiːn ˈlʊtɐ] ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation, and his theological beliefs form the basis of Lutheranism. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in Western and Christian history. Born in Eisleben, Luther was ordained to the priesthood in 1507. He came to reject several teachings and practices of the contemporary Roman Catholic Church, in particular the view on indulgences and papal authority. Luther initiated an international debate on these in works like his Ninety-five Theses, which he authored in 1517. In 1520 Pope Leo X demanded that Luther renounce all of his writings, and when Luther refused to do so, excommunicated him in January 1521. Later that year, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V condemned Luther as an outlaw at the Diet of Worms. When Luther died in 1546, his excommunication by Leo X was still in effect. Luther taught that justification is not earned by any human acts or intents or merit; rather, it is received only as the free gift of God's grace through the believer's faith in Jesus Christ. He held that good works were a necessary fruit of living faith, part of the process of sanctification. Luther's theology challenged the authority and office of the pope and bishops by teaching that the Bible is the only source of divinely revealed knowledge on the Gospel, and opposed sacerdotalism by considering all baptised Christians to be a holy priesthood. Those who identify with these, as well as Luther's wider teachings, are called Lutherans, although Luther insisted on Christian or Evangelical (German: evangelisch), as the only acceptable names for persons who professed Christ. Luther's translation of the Bible into German made the Bible vastly more accessible to the laity, which had a tremendous impact on both the Church and German culture. It fostered the development of a standard version of the German language, added several principles to the art of translation, and influenced the writing of an English translation, the Tyndale Bible. His hymns influenced the development of singing in Protestant churches. His marriage to Katharina von Bora, a former nun, set a model for the practice of clerical marriage, allowing Protestant clergy to marry. In two of his later works, such as in On the Jews and Their Lies, Luther expressed staunchly antisemitic views, calling for the expulsion of Jews and the burning of synagogues. These works also targeted Roman Catholics, Anabaptists, and nontrinitarian Christians. Luther did not directly advocate the murder of Jews; however, some historians contend that his rhetoric encouraged antisemitism in Germany and the emergence, centuries later, of the Nazi Party.

3. Hildegard of Bingen (1098 - 1179)

With an HPI of 83.03, Hildegard of Bingen is the 3rd most famous German Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 88 different languages.

Hildegard of Bingen OSB (German: Hildegard von Bingen, pronounced [ˈhɪldəɡaʁt fɔn ˈbɪŋən]; Latin: Hildegardis Bingensis; c. 1098 – 17 September 1179), also known as the Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictine abbess and polymath active as a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and as a medical writer and practitioner of the Catholic Church during the High Middle Ages. She is one of the best-known composers of sacred monophony, as well as the most recorded in modern history. She has been considered by a number of scholars to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany. Hildegard's convent at Disibodenberg elected her as magistra (mother superior) in 1136. She founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg in 1150 and Eibingen in 1165. Hildegard wrote theological, botanical, and medicinal works, as well as letters, hymns, and antiphons for the liturgy. She wrote poems, and supervised miniature illuminations in the Rupertsberg manuscript of her first work, Scivias. There are more surviving chants by Hildegard than by any other composer from the entire Middle Ages, and she is one of the few known composers to have written both the music and the words. One of her works, the Ordo Virtutum, is an early example of liturgical drama and arguably the oldest surviving morality play. She is noted for the invention of a constructed language known as Lingua Ignota. Although the history of her formal canonization is complicated, regional calendars of the Catholic Church have listed her as a saint for centuries. On 10 May 2012, Pope Benedict XVI extended the liturgical cult of Hildegard to the entire Catholic Church in a process known as "equivalent canonization". On 7 October 2012, he named her a Doctor of the Church, in recognition of "her holiness of life and the originality of her teaching."

4. Ambrose (340 - 397)

With an HPI of 81.26, Ambrose is the 4th most famous German Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 76 different languages.

Ambrose of Milan (Latin: Aurelius Ambrosius; c. 339 – 4 April 397), canonized as Saint Ambrose, was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promoting Nicene Christianity against Arianism and paganism. He left a substantial collection of writings, of which the best known include the ethical commentary De officiis ministrorum (377–391), and the exegetical Exameron (386–390). His preaching, his actions and his literary works, in addition to his innovative musical hymnography, made him one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures of the 4th century. Ambrose was serving as the Roman governor of Aemilia-Liguria in Milan when he was unexpectedly made Bishop of Milan in 374 by popular acclamation. As bishop, he took a firm position against Arianism and attempted to mediate the conflict between the emperors Theodosius I and Magnus Maximus. Tradition credits Ambrose with developing an antiphonal chant, known as Ambrosian chant, and for composing the "Te Deum" hymn, though modern scholars now reject both of these attributions. Ambrose's authorship on at least four hymns, including the well-known "Veni redemptor gentium", is secure; they form the core of the Ambrosian hymns, which includes others that are sometimes attributed to him. He also had a notable influence on Augustine of Hippo (354–430), whom he helped convert to Christianity. Western Christianity identified Ambrose, along with Augustine, Jerome and pope Gregory the Great, as one of the four Great Latin Church Fathers, declared Doctors of the Church in 1298. He is considered a saint by the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, and various Lutheran denominations, and venerated as the patron saint of Milan and beekeepers.

5. Albertus Magnus (1206 - 1280)

With an HPI of 81.25, Albertus Magnus is the 5th most famous German Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 74 different languages.

Albertus Magnus (c. 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop. He is considered one of the greatest medieval philosophers and thinkers. Canonized in 1931, he was known during his lifetime as Doctor universalis and Doctor expertus; late in his life the sobriquet Magnus was appended to his name. Scholars such as James A. Weisheipl and Joachim R. Söder have referred to him as the greatest German philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages. The Catholic Church distinguishes him as one of the Doctors of the Church.

6. Pope Joan (b. 0)

With an HPI of 80.19, Pope Joan is the 6th most famous German Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 53 different languages.

Pope Joan (Latin: Ioannes Anglicus; 855–857) is a woman who purportedly reigned as popess (female pope) for two years during the Middle Ages. Her story first appeared in chronicles in the 13th century and subsequently spread throughout Europe. The story was widely believed for centuries, but most modern scholars regard it as fictional. Most versions of her story describe her as a talented and learned woman who disguised herself as a man, often at the behest of a lover. In the most common accounts, owing to her abilities she rose through the church hierarchy and was eventually elected pope. Her sex was revealed when she gave birth during a procession and she died shortly after, either through murder or natural causes. The accounts state that later church processions avoided this spot and that the Vatican removed the female pope from its official lists and crafted a ritual to ensure that future popes were male. Pope Joan's existence was generally accepted as true until the 16th century, when several religious groups called the story into question. Until then, Joan was used as an exemplum in Dominican preaching and figured in books published in the Papal States. The Siena Cathedral, finished in 1263, featured a bust of Joan among other popes until 1600, when her depiction was repurposed into that of a male pope. Jean de Mailly's chronicle, written around 1250, contains the first known mention of an unnamed female pope and inspired several more accounts over the next several years. The most popular and influential version is that interpolated into Martin of Opava's Chronicon Pontificum et Imperatorum later in the 13th century. Martin introduced details that the female pope's birth name was John Anglicus of Mainz, that she reigned in the 9th century and that she entered the church to follow her lover. The existence of Pope Joan was used in the defence of Walter Brut in his trial of 1391. Her existence was generally accepted as true until the 16th century, when a widespread debate among Catholic and Protestant writers called the story into question: various writers noted the implausibly long gap between Joan's supposed lifetime and her first appearance in texts. Protestant scholar David Blondel ultimately demonstrated the impossibility of the story in his 1647 treatise on the issue. Pope Joan is now widely considered fictional, though the legend remains influential in cultural depictions.

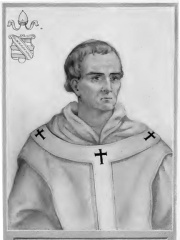

7. Pope Damasus II (1000 - 1048)

With an HPI of 80.13, Pope Damasus II is the 7th most famous German Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 69 different languages.

Pope Damasus II (; died 9 August 1048, born Poppo von Brixen) was the Bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 17 July 1048 to his death on 9 August that same year. He was the second of the German pontiffs nominated by Emperor Henry III. A native of Bavaria, he was the third German to become pope and had one of the shortest papal reigns. Upon the death of Clement II, envoys from Rome were sent to the emperor to ascertain who should be named pope. Henry named the bishop of Brixen, Poppo de' Curagnoni. While the envoys were away, the former pope Benedict IX reasserted himself and with the assistance of the disaffected Margrave Boniface III of Tuscany once again assumed the papacy. Henry ordered Boniface to escort Poppo to Rome, but Boniface declined, pointing out that the Romans had already enthroned Benedict. Enraged, the emperor ordered the margrave to depose Benedict or suffer the consequences. Poppo became pope in mid-July but died less than a month later, in Palestrina.

8. Philip Melanchthon (1497 - 1560)

With an HPI of 79.75, Philip Melanchthon is the 8th most famous German Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 67 different languages.

Philip Melanchthon (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, an intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and influential designer of educational systems. He stands next to Luther and John Calvin as a reformer, theologian, and shaper of Protestantism.

9. Pope Clement II (1005 - 1047)

With an HPI of 79.38, Pope Clement II is the 9th most famous German Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 68 different languages.

Pope Clement II (Latin: Clemens II; born Suidger von Morsleben-Horneburg; died 9 October 1047) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1046 until his death in 1047. He was the first in a series of reform-minded popes from Germany. Suidger was the bishop of Bamberg. In 1046, he accompanied King Henry III of Germany, when at the request of laity and clergy of Rome, Henry went to Italy and summoned the Council of Sutri, which deposed Benedict IX and Sylvester III, and accepted the resignation of Gregory VI. Henry suggested Suidger as the next pope, and he was then elected, taking the name of Clement II. Clement then proceeded to crown Henry as emperor. Clement's brief tenure as pope saw the enactment of more stringent prohibitions against simony.

10. Pope Victor II (1018 - 1057)

With an HPI of 73.88, Pope Victor II is the 10th most famous German Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 68 different languages.

Pope Victor II (c. 1018 – 28 July 1057), born Gebhard von Dollnstein-Hirschberg, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 April 1055 until his death in 1057. Victor II was one of a series of German-born popes who led the Gregorian Reform.

People

Pantheon has 134 people classified as German religious figures born between 300 and 1978. Of these 134, 14 (10.45%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living German religious figures include Gerhard Ludwig Müller, Walter Kasper, and Friedrich Wetter. The most famous deceased German religious figures include Pope Benedict XVI, Martin Luther, and Hildegard of Bingen. As of April 2024, 1 new German religious figures have been added to Pantheon including Stephan Burger.

Living German Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsGerhard Ludwig Müller

1947 - Present

HPI: 69.20

Walter Kasper

1933 - Present

HPI: 67.04

Friedrich Wetter

1928 - Present

HPI: 65.26

Georg Gänswein

1956 - Present

HPI: 64.92

Reinhard Marx

1953 - Present

HPI: 63.94

Walter Brandmüller

1929 - Present

HPI: 63.47

Rainer Woelki

1956 - Present

HPI: 59.43

Antje Jackelén

1955 - Present

HPI: 57.96

Brother Alois

1954 - Present

HPI: 54.42

Franz-Peter Tebartz-van Elst

1959 - Present

HPI: 51.69

Ludwig Schick

1949 - Present

HPI: 51.37

Margot Käßmann

1958 - Present

HPI: 48.80

Deceased German Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsPope Benedict XVI

1927 - 2022

HPI: 93.90

Martin Luther

1483 - 1546

HPI: 92.77

Hildegard of Bingen

1098 - 1179

HPI: 83.03

Ambrose

340 - 397

HPI: 81.26

Albertus Magnus

1206 - 1280

HPI: 81.25

Pope Joan

HPI: 80.19

Pope Damasus II

1000 - 1048

HPI: 80.13

Philip Melanchthon

1497 - 1560

HPI: 79.75

Pope Clement II

1005 - 1047

HPI: 79.38

Pope Victor II

1018 - 1057

HPI: 73.88

Thomas à Kempis

1380 - 1471

HPI: 73.86

Bruno of Cologne

1030 - 1101

HPI: 72.10

Newly Added German Religious Figures (2025)

Go to all RankingsOverlapping Lives

Which Religious Figures were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Religious Figures since 1700.