The Most Famous

RELIGIOUS FIGURES from Egypt

This page contains a list of the greatest Egyptian Religious Figures. The pantheon dataset contains 3,187 Religious Figures, 77 of which were born in Egypt. This makes Egypt the birth place of the 9th most number of Religious Figures behind Spain, and Saudi Arabia.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Egyptian Religious Figures of all time. This list of famous Egyptian Religious Figures is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Egyptian Religious Figures.

1. Moses (1393 BC - 1273 BC)

With an HPI of 93.26, Moses is the most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 160 different languages on wikipedia.

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the Exodus from Egypt. He is considered the most important prophet in Judaism and Samaritanism, and one of the most important prophets in Christianity, Islam, the Baháʼí Faith, and other Abrahamic religions. According to the Abrahamic scriptures, God dictated the Mosaic Law to Moses, which he wrote down and which formed part of the Torah. According to the Book of Exodus, Moses was born in a period when his people, the Israelites, who were an enslaved minority, were increasing in population; consequently, the Egyptian Pharaoh was worried that they might ally themselves with Egypt's enemies. When Pharaoh ordered all newborn Hebrew boys to be killed in order to reduce the population of the Israelites, Moses' Hebrew mother, Jochebed, secretly hid him in the bulrushes along the Nile river. The Pharaoh's daughter discovered the infant there and adopted him as a foundling. Thus, he grew up with the Egyptian royal family. After killing an Egyptian slave-master who was beating a Hebrew, Moses fled across the Red Sea to Midian, where he encountered the Angel of the Lord, speaking to him from within a burning bush on Mount Horeb. God sent Moses back to Egypt to demand the release of the Israelites from slavery. Moses said that he could not speak eloquently, so God allowed Aaron, his elder brother, to become his spokesperson. After the Ten Plagues, Moses led the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt and across the Red Sea, after which they based themselves at Mount Sinai, where Moses received the Ten Commandments. After 40 years of wandering in the desert, Moses died on Mount Nebo at the age of 120, within sight of the Promised Land. The majority of scholars see the biblical Moses as a legendary figure, while retaining the possibility that Moses or a Moses-like figure existed in the 13th century BCE. Rabbinic Judaism calculated a lifespan of Moses corresponding to 1391–1271 BCE; Jerome suggested 1592 BCE, and James Ussher suggested 1571 BCE as his birth year. Moses has often been portrayed in art, literature, music and film, and he is the subject of works at a number of U.S. government buildings.

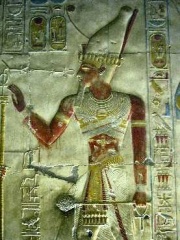

2. Tutankhamun (1341 BC - 1323 BC)

With an HPI of 88.82, Tutankhamun is the 2nd most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 109 different languages.

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen (Ancient Egyptian: twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn; c. 1341 BC – c. 1323 BC), was the thirteenth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, who ruled c. 1333 – 1323 BC. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of ancient Egyptian religion, undoing a previous shift to the religion known as Atenism. Tutankhamun's reign is considered one of the greatest restoration periods in ancient Egyptian history, and his tomb door proclaims his dedication to illustrative constructions of the ancient Egyptian gods. His endowments and restorations of cults were recorded on the Restoration Stela. The cult of the god Amun at Thebes was restored to prominence, and the royal couple changed their names to "Tutankhamun" and "Ankhesenamun", replacing the -aten suffix. He also moved the royal court from Akhenaten's capital, Amarna, back to Memphis almost immediately on his accession to the kingship. He reestablished diplomatic relations with the Mitanni and carried out military campaigns in Nubia and the Near East. Tutankhamun was one of only a few kings known to be worshipped as a deity during their lifetime. He likely began construction of a royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings and an accompanying mortuary temple, but both were unfinished at the time of his death. Tutankhamun died unexpectedly aged about 18; his health and the cause of his death have been the subject of much debate. In 2012, it was suggested he died from a combination of malaria and a leg fracture. Since his royal tomb was incomplete, he was instead buried in a small non-royal tomb adapted for the purpose. He was succeeded by his vizier Ay, who was probably an old man when he became king, and had a short reign. Ay was succeeded by Horemheb, who had been the commander-in-chief of Tutankhamun's armed forces. Under Horemheb, the restoration of the traditional ancient Egyptian religion was completed; Ay and Tutankhamun's constructions were usurped, and earlier Amarna Period rulers were erased. Tutankhamun's tomb was discovered in 1922 by excavators led by Howard Carter and his patron, George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon. Although it had clearly been raided and robbed in ancient times, it retained much of its original contents, including the king's undisturbed mummy. The discovery received worldwide press coverage; with over 5,000 artifacts, it gave rise to renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun's mask, preserved at the Egyptian Museum, remains a popular symbol. Before it was relocated to the Grand Egyptian Museum in 2025, some of his treasures have traveled worldwide, with unprecedented response; the Egyptian government allowed tours of the tomb beginning in 1961. The deaths of some individuals who were involved in the excavation have been popularly attributed to the "curse of the pharaohs" due to the similarity of their circumstances. Since the discovery of his tomb, he has been referred to colloquially as "King Tut".

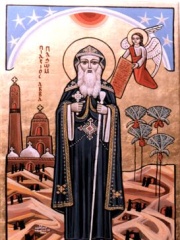

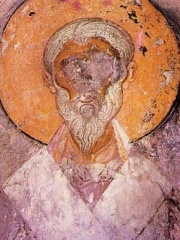

3. Anthony the Great (251 - 356)

With an HPI of 83.70, Anthony the Great is the 3rd most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 66 different languages.

Anthony the Great (c. 12 January 251 – 17 January 356) was a Christian monk from Egypt, revered since his death as a saint. He is distinguished from other saints named Anthony, such as Anthony of Padua, by various epithets: Anthony of Egypt, Anthony the Abbot, Anthony of the Desert, Anthony the Anchorite, Anthony the Hermit, and Anthony of Thebes. For his importance among the Desert Fathers and to all later Christian monasticism, he is also known as the Father of All Monks. His feast day is celebrated on 17 January among the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches and on Tobi 22 in the Coptic calendar. The biography of Anthony's life by Athanasius of Alexandria helped to spread the concept of Christian monasticism, particularly in Western Europe via its Latin translations. He is often erroneously considered the first Christian monk, but as his biography and other sources make clear, there were many ascetics before him. Anthony was, however, among the first known to go into the wilderness (about AD 270), which seems to have contributed to his renown. Accounts of Anthony enduring supernatural temptation during his sojourn in the Eastern Desert of Egypt inspired the depiction of his temptations in visual art and literature. Anthony is invoked against infectious diseases, particularly skin diseases. In the past, many such afflictions, including ergotism, erysipelas, and shingles, were referred to as Saint Anthony's fire.

4. Moses in Islam (1392 BC - 1272 BC)

With an HPI of 82.06, Moses in Islam is the 4th most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 40 different languages.

Moses (Arabic: موسى ابن عمران Mūsā ibn ʿImrān, lit. 'Moses, son of Amram') is a prominent prophet and messenger of God and is the most frequently mentioned individual in the Quran, with his name being mentioned 136 times and his life being narrated and recounted more than that of any other prophet. Apart from the Quran, Moses is also described and praised in the Hadith literature as well. He is one of the most important prophets and messengers within Islam. According to the Quran, Moses was born to an Israelite family. In his childhood, he is put in a basket which flows towards the Nile, and is eventually discovered by Pharaoh's (Fir'awn) wife (not named in the Quran but called Asiya in Hadith), who takes Moses as her adopted son. After reaching adulthood, Moses then resides in Midian, before departing for Egypt again to threaten the Pharaoh. During his prophethood, Moses is said to have performed many miracles, and is also reported to have personally talked to God, who bestows the title 'Speaker of God' (Kalīm Allāh) upon Moses. The prophet's most famous miracle is dividing the Red Sea, with a miraculous staff provided by God. After Pharaoh's death, Moses and his followers travel towards the Promised Land and the prophet dies within sight of the land. Moses is reported to have met Muhammad in the seven heavens following his ascension from Jerusalem during the Night Journey (’Isrā’ Miʿrāj). During the journey, Moses is said by Muslims to have repeatedly sent Muhammad back, and request a reduction in the number of required daily prayers, originally believed to be fifty, until only the five obligatory prayers remained. Moses is viewed as a very important figure in Islam. According to Islamic theology, all Muslims must have faith in every prophet and messenger of God, which includes Moses and his brother Aaron. The life of Moses is generally seen as a spiritual parallel to the life of Muhammad, and Muslims consider many aspects of the two individuals' lives to be shared. Islamic literature also describes a parallel relation between their people and the incidents that occurred in their lifetimes; the exodus of the Israelites from ancient Egypt is considered to be similar in nature to the migration of Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina as both events unfolded in the face of persecution—of the Israelites by the ancient Egyptians, and of the early Muslims by the Meccans, respectively. His revelations, such as the Ten Commandments, form part of the contents of the Torah and are central to the Abrahamic religions of Judaism and Christianity. Consequently, Jews and Christians are designated as "People of the Book" for Muslims and are to be recognized with this special status wherever Islamic law is applied. Moses is further revered in Islamic literature, which expands upon the incidents of his life and the miracles attributed to him in the Quran and hadith, such as his direct conversations with God. Generally, Moses is seen as a legendary figure by biblical scholars, some of whom consider it possible that Moses or a Moses-like figure existed in the 13th century BCE.

5. Catherine of Alexandria (287 - 305)

With an HPI of 81.57, Catherine of Alexandria is the 5th most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 62 different languages.

Catherine of Alexandria, also spelled Katherine, was, according to tradition, a Christian saint and virgin, who was martyred in the early 4th century at the hands of the emperor Maxentius. According to her hagiography, she was both a princess and a noted scholar who became a Christian around age 14, converted hundreds of people to Christianity, and was martyred around age 18. The Eastern Orthodox Church venerates her as a great martyr and celebrates her feast day on 24 or 25 November, depending on the regional tradition. In Catholicism, Catherine is traditionally revered as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, and she is commemorated in the Roman Martyrology on 25 November. Her feast was removed from the General Roman Calendar in 1969 but restored in 2002 as an optional memorial. In the Episcopal Church, St. Catherine is commemorated on 24 November, together with the martyrs Barbara of Nicomedia and Margaret of Antioch, while in the Church of England her feast day is 25 November. Some modern scholars consider that the legend of Catherine was probably based on the life and murder of the virgin Saint Dorothea of Alexandria and the Greek philosopher Hypatia, with the reversed role of a Christian and neoplatonist in the case of the latter. On the other hand, Leon Clugnet writing in the Catholic Encyclopedia states "although contemporary hagiographers look upon the authenticity of the various texts containing the legend of St. Catherine as more than doubtful, it is not therefore meant to cast even the shadow of a doubt around the existence of the saint".

6. Hagar (1800 BC - 2000 BC)

With an HPI of 80.49, Hagar is the 6th most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 59 different languages.

According to the Book of Genesis, Hagar is an Egyptian slave, a handmaiden of Sarah (then known as Sarai), whom Sarah gave to her own husband Abram (later renamed Abraham) as a wife to bear him a child. Abraham's firstborn son through Hagar, Ishmael, became the progenitor of the Ishmaelites, generally taken to be the Arabs. Various commentators have connected her to the Hagrites (sons of Agar), perhaps claiming her as their eponymous ancestor. Hagar is alluded to, although not named, in the Quran, and Islam considers her Abraham's second wife.

7. Joshua (1355 BC - 1245 BC)

With an HPI of 79.39, Joshua is the 7th most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 64 different languages.

Joshua ( JOSH-oo-ə), also known as Yehoshua (Hebrew: יְהוֹשֻׁעַ Yəhōšuaʿ, Tiberian: Yŏhōšuaʿ, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, was Moses' assistant in the books of Exodus and Numbers, and later succeeded Moses as leader of the Israelite tribes in the Book of Joshua of the Hebrew Bible. His name was Hoshea (הוֹשֵׁעַ Hōšēaʿ, lit. 'Save') the son of Nun, of the tribe of Ephraim, but Moses called him "Yehoshua" (translated as "Joshua" in English), the name by which he is commonly known in English. According to the Bible, he was born in Egypt prior to the Exodus. In Numbers 13:1, the Hebrew Bible identifies Joshua as one of the twelve spies of Israel sent by Moses to explore the land of Canaan. After the death of Moses, he led the Israelite tribes in the conquest of Canaan, and allocated lands to the tribes. According to biblical chronology, Joshua lived some time in the Bronze Age. According to Joshua 24:29 Joshua died at the age of 110. Joshua holds a position of respect among Muslims, who also see him as the leader of the faithful following the death of Moses. In Islam, it is also believed that Yusha bin Nun (Joshua) was the "attendant" of Moses mentioned in the Quran before Moses meets Khidr. Joshua plays a role in Islamic literature, with significant narration in the hadith.

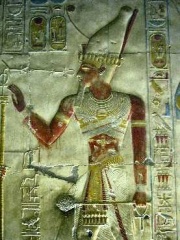

8. Seti I (1323 BC - 1279 BC)

With an HPI of 79.27, Seti I is the 8th most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 64 different languages.

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom period, ruling c. 1294 or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and the father of Ramesses II (commonly known as Ramesses the Great). The name 'Seti' means "of Set", which indicates that he was consecrated to the god Set (also termed "Sutekh" or "Seth"). As with most pharaohs, Seti had several names. Upon his ascension, he took the prenomen "mn-m3't-r' ", usually vocalized in Egyptian as Menmaatre (Established is the Justice of Re). His better known nomen, or birth name, is transliterated as "sty mry-n-ptḥ" or Sety Merenptah, meaning "Man of Set, beloved of Ptah". Manetho incorrectly considered him to be the founder of the 19th Dynasty, and gave him a reign length of 55 years, though no evidence has ever been found for so long a reign.

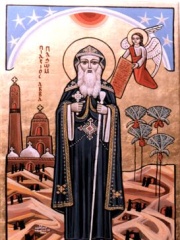

9. Pachomius the Great (292 - 348)

With an HPI of 77.97, Pachomius the Great is the 9th most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 41 different languages.

Pachomius (; Greek: Παχώμιος Pakhomios; Coptic: Ⲡⲁϧⲱⲙ; c. 292 – 9 May 348 AD), also known as Saint Pachomius the Great, is generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism. Coptic churches celebrate his feast day on 9 May, and Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches mark his feast on 15 May or 28 May. In Lutheranism, he is remembered as a renewer of the church, along with his contemporary (and fellow desert saint), Anthony of Egypt on 17 January.

10. Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (250 - 326)

With an HPI of 76.40, Pope Alexander I of Alexandria is the 10th most famous Egyptian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 39 different languages.

Alexander I of Alexandria (Koine Greek: Ἀλέξανδρος, Aléxandros) was the 19th Patriarch of Alexandria. During his patriarchate, he dealt with a number of issues facing the Church in that day. These included the dating of Easter, the actions of Meletius of Lycopolis, and the issue of greatest substance, Arianism. He was the leader of the opposition to Arianism at the First Council of Nicaea. He also mentored his successor, Athanasius of Alexandria, who would become one of the Church Fathers. He is regarded as a Pope by the Coptic Orthodox Church but not by the Catholic Church.

People

Pantheon has 77 people classified as Egyptian religious figures born between 3000 BC and 1955. Of these 77, 3 (3.90%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Egyptian religious figures include Pope Tawadros II of Alexandria, Ali Gomaa, and Ibrahim Isaac Sidrak. The most famous deceased Egyptian religious figures include Moses, Tutankhamun, and Anthony the Great.

Living Egyptian Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsPope Tawadros II of Alexandria

1952 - Present

HPI: 69.80

Ali Gomaa

1952 - Present

HPI: 57.47

Ibrahim Isaac Sidrak

1955 - Present

HPI: 55.85

Deceased Egyptian Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsMoses

1393 BC - 1273 BC

HPI: 93.26

Tutankhamun

1341 BC - 1323 BC

HPI: 88.82

Anthony the Great

251 - 356

HPI: 83.70

Moses in Islam

1392 BC - 1272 BC

HPI: 82.06

Catherine of Alexandria

287 - 305

HPI: 81.57

Hagar

1800 BC - 2000 BC

HPI: 80.49

Joshua

1355 BC - 1245 BC

HPI: 79.39

Seti I

1323 BC - 1279 BC

HPI: 79.27

Pachomius the Great

292 - 348

HPI: 77.97

Pope Alexander I of Alexandria

250 - 326

HPI: 76.40

Saint Sarah

100 - 100

HPI: 74.94

Tiye

1398 BC - 1338 BC

HPI: 74.68

Overlapping Lives

Which Religious Figures were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 7 most globally memorable Religious Figures since 1700.