The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Egypt

This page contains a list of the greatest Egyptian Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 218 of which were born in Egypt. This makes Egypt the birth place of the 16th most number of Politicians behind Ukraine, and Austria.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Egyptian Politicians of all time. This list of famous Egyptian Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Egyptian Politicians.

1. Cleopatra (69 BC - 30 BC)

With an HPI of 98.34, Cleopatra is the most famous Egyptian Politician. Her biography has been translated into 151 different languages on wikipedia.

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (Koine Greek: Κλεοπάτρα Θεά Φιλοπάτωρ, lit. 'Cleopatra father-loving goddess'; 70/69 BC – 10 or 12 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and the last active Hellenistic pharaoh. A member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, she was a descendant of its founder Ptolemy I Soter, a Macedonian Greek general and companion of Alexander the Great. Her first language was Koine Greek, and she is the only Ptolemaic ruler known to have learned the Egyptian language, among several others. After her death, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire, marking the end of the Hellenistic period in the Mediterranean, which had begun during the reign of Alexander (336–323 BC). Born in Alexandria, Cleopatra was the daughter of Ptolemy XII Auletes, who named her his heir before his death in 51 BC. Cleopatra began her reign alongside her brother Ptolemy XIII, but a falling-out between them led to a civil war. Roman statesman Pompey fled to Egypt after losing the 48 BC Battle of Pharsalus against his rival Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator, in Caesar's civil war. Pompey had been a political ally of Ptolemy XII, but Ptolemy XIII had him ambushed and killed before Caesar arrived and occupied Alexandria. Caesar then attempted to reconcile the rival Ptolemaic siblings, but Ptolemy XIII's forces besieged Cleopatra and Caesar at the palace. Shortly after the siege was lifted by reinforcements, Ptolemy XIII died in the Battle of the Nile. Caesar declared Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy XIV joint rulers, and maintained a private affair with Cleopatra which produced a son, Caesarion. Cleopatra traveled to Rome as a client queen in 46 and 44 BC, where she stayed at Caesar's villa. After Caesar's assassination, followed shortly afterwards by the sudden death of Ptolemy XIV (possibly murdered on Cleopatra's order), she named Caesarion co-ruler as Ptolemy XV. In the Liberators' civil war of 43–42 BC, Cleopatra sided with the Roman Second Triumvirate formed by Caesar's heir Octavian, Mark Antony, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. After their meeting at Tarsos in 41 BC, the queen had an affair with Antony which produced three children. Antony became increasingly reliant on Cleopatra for both funding and military aid during his invasions of the Parthian Empire and the Kingdom of Armenia. The Donations of Alexandria declared their children rulers over various territories under Antony's authority. Octavian portrayed this event as an act of treason, forced Antony's allies in the Roman Senate to flee Rome in 32 BC, and declared war on Cleopatra. After defeating Antony and Cleopatra's naval fleet at the 31 BC Battle of Actium, Octavian's forces invaded Egypt in 30 BC and defeated Antony, leading to Antony's suicide. After his death, Cleopatra reportedly killed herself, probably by poisoning, to avoid being publicly displayed by Octavian in Roman triumphal procession. Cleopatra's legacy survives in ancient and modern works of art. Roman historiography and Latin poetry produced a generally critical view of the queen that pervaded later Medieval and Renaissance literature. In the visual arts, her ancient depictions include Roman busts, paintings, and sculptures, cameo carvings and glass, Ptolemaic and Roman coinage, and reliefs. In Renaissance and Baroque art, she was the subject of many works including operas, paintings, poetry, sculptures, and theatrical dramas. She has become a pop culture icon of Egyptomania since the Victorian era, and in modern times, Cleopatra has appeared in the applied and fine arts, burlesque satire, Hollywood films, and brand images for commercial products.

2. Akhenaten (1400 BC - 1336 BC)

With an HPI of 85.92, Akhenaten is the 2nd most famous Egyptian Politician. His biography has been translated into 93 different languages.

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ-n-jtn ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy, pronounced [ˈʔuːχəʔ nə ˈjaːtəj] , meaning 'Effective for the Aten'), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning c. 1353–1336 or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Originally named Amenhotep IV (Ancient Egyptian: jmn-ḥtp, meaning "Amun is satisfied", Hellenized as Amenophis IV), in the fifth year of his reign he adopted the name "Akhenaten". As a pharaoh, Akhenaten is noted for abandoning traditional ancient Egyptian religion of polytheism and introducing Atenism, or worship centered around Aten. The views of Egyptologists differ as to whether the religious policy was absolutely monotheistic, or whether it was monolatristic, syncretistic, or henotheistic. This culture shift away from traditional religion was reversed after his death. Akhenaten's monuments were dismantled and hidden, his statues were destroyed, and his name excluded from lists of rulers compiled by later pharaohs. Traditional religious practice was gradually restored, notably under his close successor Tutankhamun, who changed his name from Tutankhaten early in his reign. When, some dozen years later, rulers without clear rights of succession from the Eighteenth Dynasty founded a new dynasty, they discredited Akhenaten and his immediate successors and referred to Akhenaten as "the enemy" or "that criminal" in archival records. Akhenaten was all but lost to history until the late-19th-century discovery of Amarna, or Akhetaten, the new capital city he built for the worship of Aten. Furthermore, in 1907 a mummy that could be Akhenaten's was unearthed from the tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings by Edward R. Ayrton. Genetic testing has determined that the man buried in KV55 was Tutankhamun's father, but its identification as Akhenaten has since been questioned. Akhenaten's rediscovery and Flinders Petrie's early excavations at Amarna sparked great public interest in the pharaoh and his queen Nefertiti. He has been described as "enigmatic", "mysterious", "revolutionary", "the greatest idealist of the world", and "the first individual in history", but also as a "heretic", "fanatic", "possibly insane", and "mad". Public and scholarly fascination with Akhenaten comes from his connection with Tutankhamun, the unique style and high quality of the pictorial arts he patronized, and the religion he attempted to establish, foreshadowing monotheism.

3. Hatshepsut (1507 BC - 1458 BC)

With an HPI of 84.03, Hatshepsut is the 3rd most famous Egyptian Politician. Her biography has been translated into 88 different languages.

Hatshepsut ( haht-SHEPP-sut; c. 1505–1458 BC) was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, ruling first as regent, then as queen regnant from c. 1479 BC until c. 1458 BC (Low Chronology) and the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Thutmose II. She was Egypt's second confirmed woman who ruled in her own right, the first being Sobekneferu/Neferusobek in the Twelfth Dynasty. Hatshepsut was the daughter of Thutmose I and Great Royal Wife, Ahmose. Upon the death of her husband and half-brother Thutmose II, she had initially ruled as regent to her stepson, Thutmose III, who inherited the throne at the age of two. Several years into her regency, Hatshepsut assumed the position of pharaoh and adopted the full royal titulary, making her a co-ruler alongside Thutmose III. In order to establish herself in the Egyptian patriarchy, she took on traditionally male roles and was depicted as a male pharaoh, with physically masculine traits and traditionally male garb. She emphasized both the qualities of men and women to convey the idea that she was both a mother and father to the realm. Hatshepsut's reign was a period of great prosperity and general peace. One of the most prolific builders in Ancient Egypt, she oversaw large-scale construction projects such as the Karnak Temple Complex, the Red Chapel, the Speos Artemidos and most famously, the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. Hatshepsut probably died in Year 22 of the reign of Thutmose III. Towards the end of the reign of Thutmose III and into the reign of his son Amenhotep II, an attempt was made to remove her from official accounts of Egyptian historiography: her statues were destroyed, her monuments were defaced, and many of her achievements were ascribed to other pharaohs.

4. Amenhotep III (1403 BC - 1350 BC)

With an HPI of 83.80, Amenhotep III is the 4th most famous Egyptian Politician. His biography has been translated into 63 different languages.

Amenhotep III (lit. '"Amun is satisfied"'), also known as Amenhotep the Magnificent or Amenhotep the Great and Hellenized as Amenophis III, was the ninth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. According to different authors following the "Low Chronology", he ruled Ancient Egypt from June 1386 to 1349 BC, or from June 1388 BC to December 1351 BC/1350 BC, after his father Thutmose IV died. Amenhotep was Thutmose's son by a minor wife, Mutemwiya. His reign marked a time of exceptional prosperity and grandeur, during which Egypt reached the height of its artistic and international influence, making him one of ancient Egypt's greatest pharaohs. He is also one of the few pharaohs worshipped as a deity during his lifetime. When he died in the 38th or 39th year of his reign, he was succeeded by his son Amenhotep IV, who later changed his name to Akhenaten.

5. Yasser Arafat (1929 - 2004)

With an HPI of 83.78, Yasser Arafat is the 5th most famous Egyptian Politician. His biography has been translated into 119 different languages.

Yasser Arafat (c. August 1929 – 11 November 2004), also popularly known by his kunya Abu Ammar, was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004, President of Palestine from 1989 to 2004 and President of the Palestinian Authority (PNA) from 1994 to 2004. Ideologically an Arab nationalist and a socialist, Arafat was a founding member of the Fatah political party, which he led from 1959 until 2004. Arafat was born to Palestinian parents in Cairo, Egypt, where he spent most of his youth. He studied at the University of King Fuad I. While a student, he embraced Arab nationalist and anti-Zionist ideas. Opposed to the 1948 creation of the State of Israel, he fought alongside the Muslim Brotherhood during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Following the defeat of Arab forces, Arafat returned to Cairo and served as president of the General Union of Palestinian Students from 1952 to 1956. In the latter part of the 1950s, Arafat co-founded Fatah, a paramilitary organization which sought Israel's replacement with a Palestinian state. Fatah operated within several Arab countries, from where it launched attacks on Israeli targets. In the latter part of the 1960s Arafat's profile grew; in 1967 he joined the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and in 1969 was elected chair of the Palestinian National Council (PNC). Fatah's growing presence in Jordan resulted in military clashes with King Hussein's Jordanian government and in the early 1970s it relocated to Lebanon. There, Fatah assisted the Lebanese National Movement during the Lebanese Civil War and continued its attacks on Israel, resulting in the organization becoming a major target of Israeli invasions during the 1978 South Lebanon conflict and 1982 Lebanon War. From 1983 to 1993, Arafat based himself in Tunisia, and began to shift his approach from open conflict with the Israelis to negotiation. In 1988, he acknowledged Israel's right to exist and sought a two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. In 1994, he returned to Palestine, settling in Gaza City and promoting self-governance for the Palestinian territories. He engaged in a series of negotiations with the Israeli government to end the conflict between it and the PLO. These included the Madrid Conference of 1991, the 1993 Oslo Accords and the 2000 Camp David Summit. The success of the negotiations in Oslo led to Arafat being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, alongside Israeli prime ministers Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres, in 1994. At the time, Fatah's support among the Palestinians declined with the growth of Hamas and other militant rivals. In late 2004, after effectively being confined within his Ramallah compound for over two years by the Israeli army, Arafat fell into a coma and died. The cause of Arafat's death remains the subject of speculation. Investigations by Russian and French teams determined no foul play was involved, while a Swiss team determined he was radiologically poisoned. Arafat remains a controversial figure. Palestinians generally view him as a martyr who symbolized the national aspirations of his people, while many Israelis regarded him as a terrorist. Palestinian rivals, including Islamists and several PLO radicals, frequently denounced him as corrupt or too submissive in his concessions to the Israeli government.

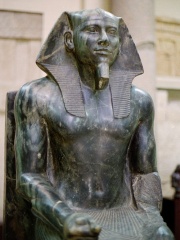

6. Khafra (2550 BC - 2479 BC)

With an HPI of 83.77, Khafra is the 6th most famous Egyptian Politician. His biography has been translated into 62 different languages.

Khafre or Chephren (died c. 2532 BC) was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the fourth king of the Fourth Dynasty, during the earlier half of the Old Kingdom period (c. 2700–2200 BC). He was son of the king Khufu, and succeeded his brother Djedefre to the throne. Khafre's enormous pyramid at Giza, the Pyramid of Khafre, is surpassed only by his father's (the Great Pyramid). The Great Sphinx of Giza was also built for him, according to some egyptologists, although this remains unconfirmed. Little is known about Khafre aside from the reports of Herodotus, a Greek historian who wrote 2,000 years later.

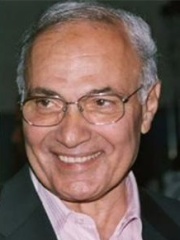

7. Hosni Mubarak (1928 - 2020)

With an HPI of 82.43, Hosni Mubarak is the 7th most famous Egyptian Politician. His biography has been translated into 116 different languages.

Muhammad Hosni El Sayed Mubarak (Arabic: محمد حسني السيد مبارك; 4 May 1928 – 25 February 2020) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the fourth president of Egypt from 1981 to 2011 and the 41st prime minister from 1981 to 1982. He was previously the 18th vice president under President Anwar Sadat from 1975 until his accession to the presidency. Before he entered politics, Mubarak was a career officer in the Egyptian Air Force. He served as its commander from 1972 to 1975 and rose to the rank of air chief marshal in 1973. After Sadat was assassinated in 1981, Mubarak assumed the presidency in a single-candidate referendum, and renewed his term through single-candidate referendums in 1987, 1993, and 1999. Under United States pressure, Mubarak held the country's first multi-party election in 2005, which he won. In 1989, he succeeded in reinstating Egypt's membership in the Arab League, which had been frozen since the Camp David Accords with Israel, and in returning the Arab League's headquarters back to Cairo. He was known for his supportive stance on the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, in addition to his role in the Gulf War. Despite providing stability and reasons for economic growth, his rule was repressive. The state of emergency, which had not been lifted since the 1967 war, stifled political opposition, the security services became known for their brutality, and corruption became widespread. Mubarak stepped down during the 2011 Egyptian revolution after 18 days of demonstrations, transferring power to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. He was later ordered to stand trial on charges of killing peaceful protesters during the revolution. These trials began on 3 August 2011, making him the first Arab leader to be tried in his own country in an ordinary court of law. On 2 June 2012, an Egyptian court sentenced Mubarak to life imprisonment. After sentencing, he was reported to have suffered a series of health crises. On 13 January 2013, Egypt's Court of Cassation (the nation's high court of appeal) overturned Mubarak's sentence and ordered a retrial. On retrial, Mubarak and his sons were convicted on 9 May 2015 of corruption and given prison sentences. Mubarak was detained in a military hospital while his sons were freed on 12 October 2015 by a Cairo court. Mubarak was acquitted on 2 March 2017 by the Court of Cassation and was released on 24 March 2017. Mubarak died in 2020, aged 91. He was honoured with a military funeral and buried at a family plot outside Cairo. Mubarak's presidency lasted almost thirty years, making him Egypt's longest-serving ruler since Muhammad Ali Pasha, who ruled the country for 43 years from 1805 to 1848.

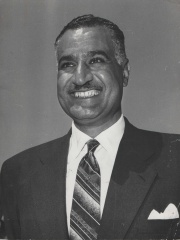

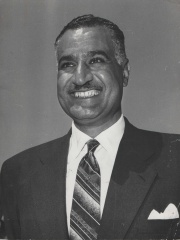

8. Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918 - 1970)

With an HPI of 82.33, Gamal Abdel Nasser is the 8th most famous Egyptian Politician. His biography has been translated into 110 different languages.

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-reaching land reforms the following year. Following a 1954 assassination attempt by a Muslim Brotherhood member, he cracked down on the organization, put President Mohamed Naguib under house arrest and assumed executive office. He was formally elected president in June 1956. Nasser's popularity in Egypt and the Arab world skyrocketed after his nationalization of the Suez Canal and his political victory in the subsequent Suez Crisis, known in Egypt as the Tripartite Aggression. Calls for pan-Arab unity under his leadership increased, culminating with the formation of the United Arab Republic with Syria from 1958 to 1961. In 1962, Nasser began a series of major socialist measures and modernization reforms in Egypt. Despite setbacks to his pan-Arabist cause, by 1963 Nasser's supporters gained power in several Arab countries, but he became embroiled in the North Yemen Civil War, and eventually the much larger Arab Cold War. He began his second presidential term in March 1965 after his political opponents were banned from running. Following Egypt's defeat by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967, Nasser resigned, but he returned to office after popular demonstrations called for his reinstatement. By 1968, Nasser had appointed himself prime minister, launched the War of Attrition to regain the Israeli-occupied Sinai Peninsula, begun a process of depoliticizing the military, and issued a set of political liberalization reforms. After the conclusion of the 1970 Arab League summit, Nasser suffered a heart attack and died. His funeral in Cairo drew five to six million mourners, and prompted an outpouring of grief across the Arab world. Nasser remains an iconic figure in the Arab world, particularly for his strides towards social justice and Arab unity, his modernization policies, and his anti-imperialist efforts. His presidency also encouraged and coincided with an Egyptian cultural boom, and the launching of large industrial projects, including the Aswan Dam, and Helwan city. Nasser's detractors criticize his authoritarianism, his human rights violations, his antisemitism, and the dominance of the military over civil institutions that characterised his tenure, establishing a pattern of military and dictatorial rule in Egypt which has persisted, nearly uninterrupted, to the present day.

9. Ay (1380 BC - 1400 BC)

With an HPI of 82.19, Ay is the 9th most famous Egyptian Politician. His biography has been translated into 52 different languages.

Ay was the penultimate pharaoh of ancient Egypt's 18th Dynasty. He held the throne of Egypt for a brief four-year period in the late 14th century BC. Prior to his rule, he was a close advisor to two, and perhaps three, other pharaohs of the dynasty. It is speculated that he was the power behind the throne during child ruler Tutankhamun's reign, although there is no evidence for this aside from Tutankhamun's youthfulness. His prenomen Kheperkheperure means "Everlasting are the Manifestations of Ra", while his nomen Ay it-netjer reads as "Ay, Father of the God". Records and monuments that can be clearly attributed to Ay are rare, both because his reign was short and because his successor, Horemheb, instigated a campaign of damnatio memoriae against him and the other pharaohs associated with the unpopular Amarna Period.

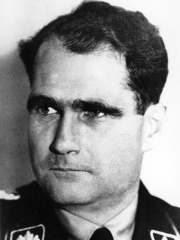

10. Rudolf Hess (1894 - 1987)

With an HPI of 81.45, Rudolf Hess is the 10th most famous Egyptian Politician. His biography has been translated into 68 different languages.

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician, convicted war criminal and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer (Stellvertreter des Führers) to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position until 1941, when he flew solo to Scotland in an attempt to negotiate the United Kingdom's exit from the Second World War. He was taken prisoner and eventually convicted of crimes against peace. He was still serving his life sentence at the time of his suicide in 1987. Hess enlisted as an infantryman in the Imperial German Army at the outbreak of World War I. He was wounded several times during the war and was awarded the Iron Cross, 2nd Class, in 1915. Shortly before the war ended, he enrolled to train as an aviator, but he saw no action in that role. He left the armed forces in December 1918 with the rank of Leutnant der Reserve. In 1919, he enrolled in the University of Munich, where he studied geopolitics under Karl Haushofer, a proponent of the concept of Lebensraum ('living space'), which became one of the pillars of Nazi ideology. He joined the Nazi Party on 1 July 1920 and was at Hitler's side on 8 November 1923 for the Beer Hall Putsch, a failed Nazi attempt to seize control of the government of Bavaria. While serving a prison sentence for this attempted coup, he assisted Hitler with Mein Kampf, which became a foundation of the political platform of the Nazi Party. After Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933, Hess was appointed Deputy Führer of the Nazi Party in April. He was elected to the Reichstag in the March elections, was made a Reichsleiter of the Nazi Party in June, and in December 1933, he became Minister without Portfolio in Hitler's cabinet. He was also appointed in 1938 to the Cabinet Council and to the Council of Ministers for Defence of the Reich in August 1939. Hitler decreed on the outbreak of war on 1 September 1939 that Hermann Göring was his official successor, and named Hess as next in line. In addition to appearing on Hitler's behalf at speaking engagements and rallies, Hess signed into law much of the government's legislation, including the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which stripped the Jews of Germany of their rights in the lead-up to the Holocaust. By the start of the war, Hess was sidelined from most important decisions, and many in Hitler's inner circle thought him to be mad. On 10 May 1941, Hess made a solo flight to Scotland, where he hoped to arrange peace talks with the Duke of Hamilton, whom he believed to be a prominent opponent of the British government's war policy. The British authorities arrested Hess immediately on his arrival and held him in custody until the end of the war, when he was returned to Germany to stand trial at the 1946 Nuremberg trials of major war criminals. During much of his trial, he claimed to be suffering from amnesia, but he later admitted to the tribunal that this had been a ruse. The tribunal convicted him of crimes against peace and of conspiracy with other German leaders to commit crimes. He served a life sentence in Spandau Prison; the Soviet Union blocked repeated attempts by family members and prominent politicians to procure his early release. While still in custody as the only prisoner in Spandau, he hanged himself in 1987 at the age of 93. After his death, the prison was demolished to prevent it from becoming a neo-Nazi shrine. His grave, bearing the inscription Ich hab's gewagt ("I dared it"), became a site of regular pilgrimage and demonstrations by neo-Nazis. In 2011, authorities refused to renew the lease on the gravesite, and his remains were exhumed and cremated and the gravestone was destroyed.

People

Pantheon has 218 people classified as Egyptian politicians born between 3500 BC and 1973. Of these 218, 15 (6.88%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Egyptian politicians include Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Fuad II of Egypt, and Mohammed Badie. The most famous deceased Egyptian politicians include Cleopatra, Akhenaten, and Hatshepsut. As of April 2024, 1 new Egyptian politicians have been added to Pantheon including Dina Powell.

Living Egyptian Politicians

Go to all RankingsAbdel Fattah el-Sisi

1954 - Present

HPI: 77.90

Fuad II of Egypt

1952 - Present

HPI: 69.01

Mohammed Badie

1943 - Present

HPI: 67.21

Ahmed Shafik

1941 - Present

HPI: 65.31

Ahmed Aboul Gheit

1942 - Present

HPI: 62.69

Moustafa Madbouly

1966 - Present

HPI: 61.39

Hazem El Beblawi

1936 - Present

HPI: 60.97

Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu

1943 - Present

HPI: 60.54

Ibrahim Mahlab

1949 - Present

HPI: 60.01

Gamal Mubarak

1963 - Present

HPI: 55.17

Ahmed al-Senussi

1933 - Present

HPI: 53.18

Amr Khaled

1967 - Present

HPI: 48.70

Deceased Egyptian Politicians

Go to all RankingsCleopatra

69 BC - 30 BC

HPI: 98.34

Akhenaten

1400 BC - 1336 BC

HPI: 85.92

Hatshepsut

1507 BC - 1458 BC

HPI: 84.03

Amenhotep III

1403 BC - 1350 BC

HPI: 83.80

Yasser Arafat

1929 - 2004

HPI: 83.78

Khafra

2550 BC - 2479 BC

HPI: 83.77

Hosni Mubarak

1928 - 2020

HPI: 82.43

Gamal Abdel Nasser

1918 - 1970

HPI: 82.33

Ay

1380 BC - 1400 BC

HPI: 82.19

Rudolf Hess

1894 - 1987

HPI: 81.45

Anwar Sadat

1918 - 1981

HPI: 81.32

Caesarion

47 BC - 30 BC

HPI: 79.18

Newly Added Egyptian Politicians (2025)

Go to all RankingsOverlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.