The Most Famous

EXPLORERS from Norway

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Norwegian Explorers of all time. This list of famous Norwegian Explorers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Norwegian Explorers.

1. Roald Amundsen (1872 - 1928)

With an HPI of 84.99, Roald Amundsen is the most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 160 different languages on wikipedia.

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (UK: , US: ; Norwegian: [ˈrùːɑɫ ˈɑ̂mʉnsən] ; 16 July 1872 – c. 18 June 1928) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen began his career as a polar explorer as first mate on Adrien de Gerlache's Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899. From 1903 to 1906, he led the first expedition to successfully traverse the Northwest Passage on the sloop Gjøa. In 1909, Amundsen began planning for a South Pole expedition. He left Norway in June 1910 on the ship Fram and reached Antarctica in January 1911. His party established a camp at the Bay of Whales and a series of supply depots on the Barrier (now known as the Ross Ice Shelf) before setting out for the pole in October. The party of five, led by Amundsen, became the first to reach the South Pole on 14 December 1911. Following a failed attempt in 1918 to reach the North Pole by traversing the Northeast Passage on the ship Maud, Amundsen began planning for an aerial expedition instead. On 12 May 1926, Amundsen and 15 other men in the airship Norge became the first explorers verified to have reached the North Pole. Amundsen disappeared in June 1928 while flying on a rescue mission for the airship Italia in the Arctic. The search for his remains, which have not been found, was called off that September.

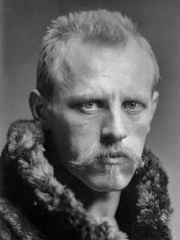

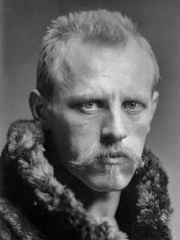

2. Fridtjof Nansen (1861 - 1930)

With an HPI of 80.38, Fridtjof Nansen is the 2nd most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 88 different languages.

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (Norwegian: [ˈfrɪ̂tːjɔf ˈnɑ̀nsn̩]; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, a scientist, a diplomat, a humanitarian, and the co-founder of the Fatherland League. He led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, traversing the island on cross-country skis. He won international fame after reaching a record northern latitude of 86°14′ during his Fram expedition of 1893–1896. Although he retired from exploration after his return to Norway, his techniques of polar travel and his innovations in equipment and clothing influenced a generation of subsequent Arctic and Antarctic expeditions. He was elected an International Member of the American Philosophical Society in 1897. Nansen studied zoology at the Royal Frederick University in Christiania and later worked as a curator at the University Museum of Bergen where his research on the central nervous system of lower marine creatures earned him a doctorate and helped establish neuron doctrine. Later, neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal won the 1906 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his research on the same subject. After 1896 his main scientific interest switched to oceanography; in the course of his research he made many scientific cruises, mainly in the North Atlantic, and contributed to the development of modern oceanographic equipment. As one of his country's leading citizens, in 1905 Nansen spoke out for ending Norway's union with Sweden, and was instrumental in persuading Prince Carl of Denmark to accept the throne of the newly independent Norway. Between 1906 and 1908, he served as the Norwegian representative in London, where he helped negotiate the Integrity Treaty that guaranteed Norway's independent status. In the final decade of his life, Nansen devoted himself primarily to the League of Nations, following his appointment in 1921 as the League's High Commissioner for Refugees. In 1922 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on behalf of the displaced victims of World War I and related conflicts. Among the initiatives he introduced was the "Nansen passport" for stateless persons, a certificate that used to be recognized by more than 50 countries. He worked on behalf of refugees alongside Vidkun Quisling until his sudden death in 1930, after which the League established the Nansen International Office for Refugees to ensure that his work continued. This office received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1938. His name is commemorated in numerous geographical features, particularly in the polar regions.

3. Erik the Red (950 - 1003)

With an HPI of 79.56, Erik the Red is the 3rd most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 63 different languages.

Erik Thorvaldsson (c. 950 – c. 1003), known as Erik the Red (Norwegian: Erik den røde), was a Norse explorer, described in medieval and Icelandic saga sources as having founded the first European settlement in Greenland. He most likely earned the epithet "the Red" due to the color of his hair and beard. According to Icelandic sagas, Erik was born in the Jæren district of Rogaland, Norway, the son of Thorvald Asvaldsson. When Thorvald was banished from Norway, the family sailed west to Iceland. During Erik's life in Iceland, he married Þjódhild Jorundsdottir and had four children, including Icelandic explorer Leif Erikson. Around the year of 982, Erik was exiled from Iceland for three years, during which time he explored Greenland, eventually culminating in his founding of the first successful European settlement on the island. Erik died there around 1003 CE during a winter epidemic.

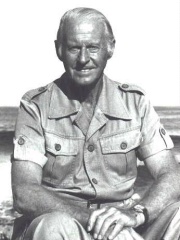

4. Thor Heyerdahl (1914 - 2002)

With an HPI of 77.14, Thor Heyerdahl is the 4th most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 77 different languages.

Thor Heyerdahl KStJ (Norwegian pronunciation: [tuːr ˈhæ̀ɪəɖɑːɫ]; 6 October 1914 – 18 April 2002) was a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer with a background in biology with specialization in zoology, botany and geography. Heyerdahl is notable for his Kon-Tiki expedition in 1947, in which he drifted 8,000 km (5,000 mi) across the Pacific Ocean in a primitive hand-built raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands. The expedition was supposed to demonstrate that the legendary sun-worshiping red-haired, bearded, and white-skinned "Tiki people" from South America drifted and colonized Polynesia first, before actual Polynesian peoples. His hyperdiffusionist ideas on ancient cultures had been widely rejected by the scientific community, even before the expedition. Heyerdahl made other voyages to demonstrate the possibility of contact between widely separated ancient peoples, notably the Ra II expedition of 1970, when he sailed from the west coast of Africa to Barbados in a papyrus reed boat. He was appointed a government scholar in 1984. He died on 18 April 2002 in Colla Micheri, Italy, while visiting close family members. The Norwegian government gave him a state funeral in Oslo Cathedral on 26 April 2002. In May 2011, the Thor Heyerdahl Archives were added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register. At the time, this list included 238 collections from all over the world. The Heyerdahl Archives span the years 1937 to 2002 and include his photographic collection, diaries, private letters, expedition plans, articles, newspaper clippings, and original book and article manuscripts. The Heyerdahl Archives are administered by the Kon-Tiki Museum and the National Library of Norway in Oslo.

5. Ingólfr Arnarson (850 - 910)

With an HPI of 73.03, Ingólfr Arnarson is the 5th most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 49 different languages.

Ingolfr Arnarson, in some sources named Bjǫrnolfsson, (c. 849 – c. 910) is commonly recognized as the first permanent Norse settler of Iceland, together with his wife Hallveig Fróðadóttir and foster brother Hjǫrleifr Hróðmarsson. According to tradition, they settled in Reykjavík in 874.

6. Otto Sverdrup (1854 - 1930)

With an HPI of 64.39, Otto Sverdrup is the 6th most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 30 different languages.

Otto Neumann Knoph Sverdrup (31 October 1854 – 26 November 1930) was a Norwegian sailor and Arctic explorer.

7. Carsten Borchgrevink (1864 - 1934)

With an HPI of 63.80, Carsten Borchgrevink is the 7th most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 28 different languages.

Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink (1 December 1864 – 21 April 1934) was a Norwegian polar explorer and a pioneer of Antarctic travel. He inspired Sir Robert Falcon Scott, Sir Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen, and others associated with the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Borchgrevink was born and raised in Christiania (now Oslo) as the son of a Norwegian lawyer and an English-born immigrant mother. He began his exploring career in 1894 by joining a Norwegian whaling expedition, during which he became one of the first people to set foot on the Antarctic mainland. This achievement helped him to obtain backing for his Southern Cross expedition, which became the first to overwinter on the Antarctic mainland, and the first to visit the Great Ice Barrier since the expedition of Sir James Clark Ross nearly sixty years earlier. The expedition's successes were received with only moderate interest by the public – and by the British geographical establishment, whose attention was by then focused on Scott's upcoming Discovery expedition. Some of Borchgrevink's colleagues were critical of his leadership, and his own accounts of the expedition were regarded as journalistic and unreliable. From 1898 to 1900, Borchgrevink led the British-financed Southern Cross expedition. He was one of three scientists in 1902 to report on the aftermath of the Mount Pelée eruption on Martinique. Thereafter he returned to Kristiania, leading a life mainly away from public attention. His pioneering work was subsequently recognised and honoured by several countries, and in 1912 he received a tribute from Roald Amundsen, leader of the first expedition to reach the South Pole. In 1930, the Royal Geographical Society acknowledged Borchgrevink's contribution to polar exploration and awarded him its Patron's Medal. The Society acknowledged in its citation that justice had not previously been done to the work of the Southern Cross expedition.

8. Ohthere of Hålogaland (900 - 901)

With an HPI of 62.25, Ohthere of Hålogaland is the 8th most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 22 different languages.

Ohthere of Hålogaland (Norwegian: Ottar fra Hålogaland) was a Viking Age Norwegian seafarer known only from an account of his travels that he gave to King Alfred (r. 871–99) of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex in about 890 AD. His account was incorporated into an Old English adaptation of a Latin historical book written early in the fifth century by Paulus Orosius, called Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII, or Seven Books of History Against the Pagans. The Old English version of this book is believed to have been written in Wessex in King Alfred's lifetime or soon after his death, and the earliest surviving copy is attributed to the same place and time. In his account, Ohthere said that his home was in "Halgoland", or Hålogaland, where he lived "north-most of all Norwegians … [since] no-one [lived] to the north of him". Ohthere spoke of his travels north to the White Sea, and south to Denmark, describing both journeys in some detail. He also spoke of Sweoland (central Sweden), the Sami people (Finnas), and of two peoples called the Cwenas, living in Cwena land to the north of the Swedes, and the Beormas, whom he found living by the White Sea. Ohthere reported that the Beormas spoke a language related to that of the Sami. Ohthere's story is the earliest known written source for the term "Denmark" (dena mearc), and perhaps also for "Norway" (norðweg). Ohthere's home may have been in the vicinity of Tromsø, in southern Troms county, northern Norway. Ohthere was involved in the fur trade.

9. Naddodd (b. 900)

With an HPI of 61.92, Naddodd is the 9th most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 22 different languages.

Naddodd (Old Norse: Naddoðr [ˈnɑdːoðr] or Naddaðr [ˈnɑdːɑðr]; Icelandic: Naddoður [ˈnatːɔːðʏr̥]; Faroese: Naddoddur; fl. c. 9th century) was a Norse Viking who is credited with the discovery of Iceland.

10. Carl Anton Larsen (1860 - 1924)

With an HPI of 61.86, Carl Anton Larsen is the 10th most famous Norwegian Explorer. His biography has been translated into 26 different languages.

Carl Anton Larsen (7 August 1860 – 8 December 1924) was a Norwegian-born whaler and Antarctic explorer who made important contributions to the exploration of Antarctica, the most significant being the first discovery of fossils for which he received the Back Grant from the Royal Geographical Society. In December 1893 he became the first person to ski in Antarctica on the Larsen Ice Shelf which was subsequently named after him. In 1904, Larsen re-founded a whaling settlement at Grytviken on the island of South Georgia. In 1910, after some years' residence on South Georgia, he renounced his Norwegian citizenship and took British citizenship. The Norwegian whale factory ship C.A. Larsen was named after him.

People

Pantheon has 26 people classified as Norwegian explorers born between 801 and 1963. Of these 26, 1 (3.85%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Norwegian explorers include Erling Kagge. The most famous deceased Norwegian explorers include Roald Amundsen, Fridtjof Nansen, and Erik the Red.

Living Norwegian Explorers

Go to all RankingsDeceased Norwegian Explorers

Go to all RankingsRoald Amundsen

1872 - 1928

HPI: 84.99

Fridtjof Nansen

1861 - 1930

HPI: 80.38

Erik the Red

950 - 1003

HPI: 79.56

Thor Heyerdahl

1914 - 2002

HPI: 77.14

Ingólfr Arnarson

850 - 910

HPI: 73.03

Otto Sverdrup

1854 - 1930

HPI: 64.39

Carsten Borchgrevink

1864 - 1934

HPI: 63.80

Ohthere of Hålogaland

900 - 901

HPI: 62.25

Naddodd

900 - Present

HPI: 61.92

Carl Anton Larsen

1860 - 1924

HPI: 61.86

Helge Ingstad

1899 - 2001

HPI: 61.81

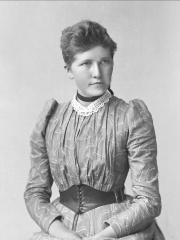

Thekla Resvoll

1871 - 1948

HPI: 61.06

Overlapping Lives

Which Explorers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 15 most globally memorable Explorers since 1700.