The Most Famous

Explorers from Spain

Top 10 Explorers

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Spanish Explorers of all time. This list of famous Spanish Explorers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Spanish Explorers.

- #1

Hernán Cortés

1485 - 1547

HPI 85.59145 langsHernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador who conquered the Aztec Empire in Mexico in the 16th century.

- #2

Francisco Pizarro

1478 - 1541

HPI 82.0587 langsFrancisco Pizarro was most famous for being the conquistador who conquered the Inca Empire.

- #3

Juan Sebastián Elcano

1476 - 1526

HPI 77.9161 langsJuan Sebastián Elcano is most famous for being the first person to circumnavigate the world.

- #4

Vasco Núñez de Balboa

1475 - 1519

HPI 75.0258 langsVasco Núñez de Balboa was a Spanish explorer who discovered the Pacific Ocean.

- #5

Francisco de Orellana

1511 - 1546

HPI 73.9350 langsFrancisco de Orellana is most famous for being the first European to explore the Amazon River.

- #6

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado

1510 - 1554

HPI 73.7241 langsFrancisco Vázquez de Coronado was a Spanish explorer who was most famous for leading an expedition to the American Southwest in search of...Read moreShow less

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado was a Spanish explorer who was most famous for leading an expedition to the American Southwest in search of the Seven Cities of Gold.

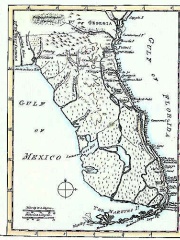

- #7

Juan Ponce de León

1460 - 1521

HPI 73.6461 langsJuan Ponce de León is most famous for being the first European to reach Florida. He was also the first governor of Puerto Rico.

- #8

Diego de Almagro

1475 - 1538

HPI 72.5146 langsDiego de Almagro is most famous for being the first European to explore Chile and Peru. He was also a Spanish conquistador who participated...Read moreShow less

Diego de Almagro is most famous for being the first European to explore Chile and Peru. He was also a Spanish conquistador who participated in the conquest of Peru, Chile, and Bolivia.

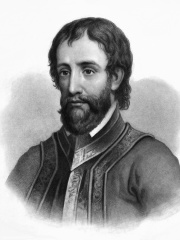

- #9

Hernando de Soto

1500 - 1542

HPI 71.1367 langsHernando de Soto was a Spanish explorer who is most famous for exploring the Mississippi River.

- #10

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar

1465 - 1524

HPI 70.3740 langsDiego Velázquez de Cuéllar was a Spanish conquistador and explorer. He was most famous for his exploration of the Yucatán Peninsula.

People by Birth Decade

Browse notable Spanish Explorers grouped by birth decade. Each decade shows the top 10 by HPI; expand to see everyone.