The Most Famous

BIOLOGISTS from United Kingdom

This page contains a list of the greatest British Biologists. The pantheon dataset contains 1,097 Biologists, 190 of which were born in United Kingdom. This makes United Kingdom the birth place of the 3rd most number of Biologists behind United States, and Germany.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary British Biologists of all time. This list of famous British Biologists is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of British Biologists.

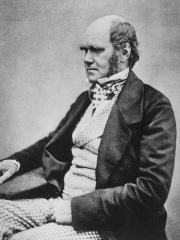

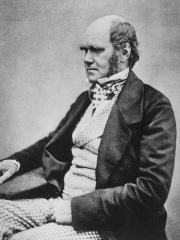

1. Charles Darwin (1809 - 1882)

With an HPI of 91.48, Charles Darwin is the most famous British Biologist. His biography has been translated into 205 different languages on wikipedia.

Charles Robert Darwin ( DAR-win; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended from a common ancestor is now generally accepted and considered a fundamental scientific concept. In a joint presentation with Alfred Russel Wallace, he introduced his scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process he called natural selection, in which the struggle for existence has a similar effect to the artificial selection involved in selective breeding. Darwin has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history and was honoured by burial in Westminster Abbey. Darwin's early interest in nature led him to neglect his medical education at the University of Edinburgh; instead, he helped Robert Edmond Grant to investigate marine invertebrates. His studies at the University of Cambridge's Christ's College from 1828 to 1831 encouraged his passion for natural science. However, it was his five-year voyage on HMS Beagle from 1831 to 1836 that truly established Darwin as an eminent geologist. The observations and theories he developed during his voyage supported Charles Lyell's concept of gradual geological change. Publication of his journal of the voyage made Darwin famous as a popular author. His first scientific work was The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs (1842). Along with his work on barnacles, it won him the Royal Medal in 1853. Puzzled by the geographical distribution of wildlife and fossils he collected on the voyage, Darwin began detailed investigations and, in 1838, devised his theory of natural selection. Although he discussed his ideas with several naturalists, he needed time for extensive research, and his geological work had priority. He was writing up his theory in 1858 when Wallace sent him an essay that described the same idea, prompting the immediate joint submission of both their theories to the Linnean Society of London. Darwin's work established evolutionary descent with modification as the dominant scientific explanation of natural diversification. Darwin published his theory of evolution with compelling evidence in On the Origin of Species (1859). Darwin's work established evolutionary descent with modification as the dominant scientific explanation of natural diversification. He explored coevolution in Fertilisation of Orchids (1862) and human evolution and sexual selection in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) was an early work of psychology, and one of the first books to feature photographs. His final book was The Formation of Vegetable Mould, through the Actions of Worms (1881). By the 1870s, the scientific community and a majority of the educated public had accepted evolution as a fact. However, many initially favoured competing explanations that gave only a minor role to natural selection. It was not until the emergence of the modern evolutionary synthesis from the 1930s to the 1950s that a broad consensus developed in which natural selection was the basic mechanism of evolution. Darwin's discovery is the unifying theory of the life sciences, explaining the unity and diversity of life.

2. Alexander Fleming (1881 - 1955)

With an HPI of 84.76, Alexander Fleming is the 2nd most famous British Biologist. His biography has been translated into 116 different languages.

Sir Alexander Fleming (6 August 1881 – 11 March 1955) was a Scottish physician and microbiologist, best known for discovering the world's first broadly effective antibiotic substance, which he named penicillin. His discovery in 1928 of what was later named benzylpenicillin (or penicillin G) from the mould Penicillium rubens has been described as the "single greatest victory ever achieved over disease". For this discovery, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Howard Florey and Ernst Chain. He also discovered the enzyme lysozyme from his nasal discharge in 1922, and along with it a bacterium he named Micrococcus lysodeikticus, later renamed Micrococcus luteus. Fleming was knighted for his scientific achievements in 1944. In 1999, he was named in Time magazine's list of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th century. In 2002, he was chosen in the BBC's television poll for determining the 100 Greatest Britons, and in 2009, he was also voted third "greatest Scot" in an opinion poll conducted by STV, behind only Robert Burns and William Wallace.

3. Rosalind Franklin (1920 - 1958)

With an HPI of 79.24, Rosalind Franklin is the 3rd most famous British Biologist. Her biography has been translated into 94 different languages.

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 1920 – 16 April 1958) was an English chemist and X-ray crystallographer. Her work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, coal, and graphite. Although her works on coal and viruses were appreciated in her lifetime, Franklin's contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA were largely unrecognised during her life, for which Franklin has been variously referred to as the "wronged heroine", the "dark lady of DNA", the "forgotten heroine", a "feminist icon", and the "Sylvia Plath of molecular biology". Franklin graduated in 1941 with a degree in natural sciences from Newnham College, Cambridge, and then enrolled for a PhD in physical chemistry under Ronald George Wreyford Norrish, the 1920 Chair of Physical Chemistry at the University of Cambridge. Disappointed by Norrish's lack of enthusiasm, she took up a research position under the British Coal Utilisation Research Association (BCURA) in 1942. The research on coal helped Franklin earn a PhD from Cambridge in 1945. Moving to Paris in 1947 as a chercheur (postdoctoral researcher) under Jacques Mering at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l'État, she became an accomplished X-ray crystallographer. After joining King's College London in 1951 as a research associate, Franklin discovered some key properties of DNA, which eventually facilitated the correct description of the double helix structure of DNA. Owing to disagreement with her director, John Randall, and her colleague Maurice Wilkins, Franklin was compelled to move to Birkbeck College in 1953. Franklin is best known for her work on the X-ray diffraction images of DNA while at King's College London, particularly Photo 51, taken by her student Raymond Gosling, which led to the discovery of the DNA double helix for which Francis Crick, James Watson, and Maurice Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. While Gosling actually took the famous Photo 51, Maurice Wilkins showed it to James Watson without Franklin's permission. Watson suggested that Franklin would have ideally been awarded a Nobel Prize in Chemistry, along with Wilkins, but it was not possible because the pre-1974 rule dictated that a Nobel prize could not be awarded posthumously unless the nomination had been made for a then-alive candidate before 1 February of the award year and Franklin died a few years before 1962, when the discovery of the structure of DNA was recognised by the Nobel committee. Working under John Desmond Bernal, Franklin led pioneering work at Birkbeck on the molecular structures of viruses. On the day before she was to unveil the structure of tobacco mosaic virus at an international fair in Brussels, Franklin died of ovarian cancer at age 37 in 1958. Her team member Aaron Klug continued her research, winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982.

4. Robert Edwards (1925 - 2013)

With an HPI of 78.39, Robert Edwards is the 4th most famous British Biologist. His biography has been translated into 71 different languages.

Sir Robert Geoffrey Edwards (27 September 1925 – 10 April 2013) was a British physiologist and pioneer in reproductive medicine, and in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) in particular. Along with obstetrician and gynaecologist Patrick Steptoe and nurse and embryologist Jean Purdy, Edwards successfully pioneered conception through IVF, which led to the birth of Louise Brown on 25 July 1978. They founded the first IVF programme for infertile patients and trained other scientists in their techniques. Edwards was the founding editor-in-chief of Human Reproduction in 1986. In 2010, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for the development of in vitro fertilization".

5. Robert Brown (1773 - 1858)

With an HPI of 78.23, Robert Brown is the 5th most famous British Biologist. His biography has been translated into 60 different languages.

Robert Brown (21 December 1773 – 10 June 1858) was a Scottish botanist and paleobotanist who made important contributions to botany largely through his pioneering use of the microscope. His contributions include one of the earliest detailed descriptions of the cell nucleus and cytoplasmic streaming; the observation of Brownian motion; early work on plant pollination and fertilisation, including being the first to recognise the fundamental difference between gymnosperms and angiosperms; and some of the earliest studies in palynology. He also made numerous contributions to plant taxonomy, notably erecting a number of plant families that are still accepted today; and numerous Australian plant genera and species, the fruit of his exploration of that continent with Matthew Flinders. The standard author abbreviation R.Br. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.

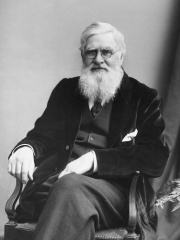

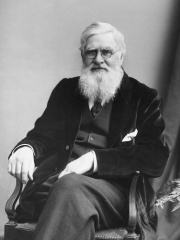

6. Alfred Russel Wallace (1823 - 1913)

With an HPI of 77.41, Alfred Russel Wallace is the 6th most famous British Biologist. His biography has been translated into 86 different languages.

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 paper on the subject was published that year alongside extracts from Charles Darwin's writings on the topic. It spurred Darwin to set aside the "big species book" he was drafting and to quickly write an abstract of it, which was published in 1859 as On the Origin of Species. Wallace did extensive fieldwork, starting in the Amazon River basin. He then did fieldwork in the Malay Archipelago, where he identified the faunal divide now termed the Wallace Line, which separates the Indonesian archipelago into two distinct parts: a western portion in which the animals are largely of Asian origin, and an eastern portion where the fauna reflect Australasia. He was considered the 19th century's leading expert on the geographical distribution of animal species, and is sometimes called the "father of biogeography", or more specifically of zoogeography. Wallace was one of the leading evolutionary thinkers of the 19th century, working on warning coloration in animals and reinforcement (sometimes known as the Wallace effect), a way that natural selection could contribute to speciation by encouraging the development of barriers against hybridisation. Wallace's 1904 book Man's Place in the Universe was the first serious attempt by a biologist to evaluate the likelihood of life on other planets. He was one of the first scientists to write a serious exploration of whether there was life on Mars. Aside from scientific work, he was a social activist, critical of what he considered to be an unjust social and economic system in 19th-century Britain. His advocacy of spiritualism and his belief in a non-material origin for the higher mental faculties of humans strained his relationship with other scientists. He was one of the first prominent scientists to raise concerns over the environmental impact of human activity. He wrote prolifically on both scientific and social issues; his account of his adventures and observations during his explorations in Southeast Asia, The Malay Archipelago, was first published in 1869. It continues to be both popular and highly regarded.

7. John Boyd Orr (1880 - 1971)

With an HPI of 76.14, John Boyd Orr is the 7th most famous British Biologist. His biography has been translated into 49 different languages.

John Boyd Orr, 1st Baron Boyd-Orr, (23 September 1880 – 25 June 1971), styled Sir John Boyd Orr from 1935 to 1949, was a Scottish teacher, medical doctor, biologist, nutritional physiologist, politician, businessman and farmer who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his scientific research into nutrition and his work as the first Director-General of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). He was the co-founder and the first President (1960–1971) of the World Academy of Art and Science (WAAS). In 1945, he was elected President of the National Peace Council and was President of the World Union of Peace Organisations and the World Movement for World Federal Government.

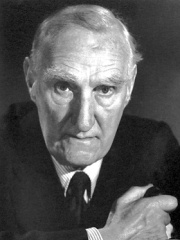

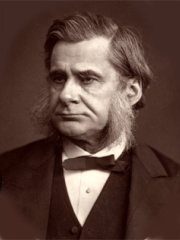

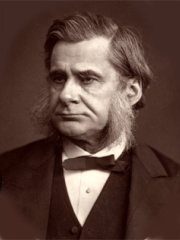

8. Thomas Henry Huxley (1825 - 1895)

With an HPI of 75.76, Thomas Henry Huxley is the 8th most famous British Biologist. His biography has been translated into 73 different languages.

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialised in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. The stories regarding Huxley's famous 1860 Oxford evolution debate with Samuel Wilberforce were a key moment in the wider acceptance of evolution and in his own career, although some historians think that aspects of the surviving story of the debate are a later fabrication. Huxley had been planning to leave Oxford on the previous day, but, after an encounter with Robert Chambers, the author of Vestiges, he changed his mind and decided to join the debate. Wilberforce was coached by Richard Owen, against whom Huxley also debated about whether humans were closely related to apes. Huxley was slow to accept some of Darwin's ideas, such as gradualism, and was undecided about natural selection, but despite this, he was wholehearted in his public support of Darwin. Instrumental in developing scientific education in Britain, he fought against the more extreme versions of religious tradition. Huxley coined the term "agnosticism" in 1869 and elaborated on it in 1889 to frame the nature of claims in terms of what is knowable and what is not. Huxley had little formal schooling and was virtually self-taught. According to Edward Poulton, he became perhaps the finest comparative anatomist of the later 19th century. He worked on invertebrates, clarifying relationships between groups previously little understood. Later, he worked on vertebrates, especially on the relationship between apes and humans. After comparing Archaeopteryx with Compsognathus, he concluded that birds evolved from small carnivorous dinosaurs, a view now held by modern biologists. The tendency has been for this fine anatomical work to be overshadowed by his energetic and controversial activity in favour of evolution, and by his extensive public work on scientific education, both of which had significant effects on society in Britain and elsewhere. Huxley's 1893 Romanes Lecture, "Evolution and Ethics", is exceedingly influential in China; the Chinese translation of Huxley's lecture even transformed the Chinese translation of Darwin's Origin of Species.

9. John Sulston (1942 - 2018)

With an HPI of 75.52, John Sulston is the 9th most famous British Biologist. His biography has been translated into 53 different languages.

Sir John Edward Sulston (27 March 1942 – 6 March 2018) was a British biologist and academic who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the cell lineage and genome of the worm Caenorhabditis elegans in 2002 with his colleagues Sydney Brenner and Robert Horvitz at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology. He was a leader in human genome research and Chair of the Institute for Science, Ethics and Innovation at the University of Manchester. Sulston was in favour of science in the public interest, such as free public access of scientific information and against the patenting of genes and the privatisation of genetic technologies.

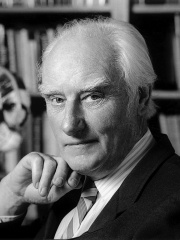

10. Francis Crick (1916 - 2004)

With an HPI of 74.94, Francis Crick is the 10th most famous British Biologist. His biography has been translated into 90 different languages.

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical structure of the DNA molecule. Crick and Watson's paper in Nature in 1953 laid the groundwork for understanding DNA structure and functions. Together with Maurice Wilkins, they were jointly awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material". Crick was an important theoretical molecular biologist and played a crucial role in research related to revealing the helical structure of DNA. He is widely known for the use of the term "central dogma" to summarise the idea that once information is transferred from nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) to proteins, it cannot flow back to nucleic acids. In other words, the final step in the flow of information from nucleic acids to proteins is irreversible. During the remainder of his career, Crick held the post of J.W. Kieckhefer Distinguished Research Professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California. His later research centred on theoretical neurobiology and attempts to advance the scientific study of human consciousness. Crick remained in this post until his death in 2004; "he was editing a manuscript on his death bed, a scientist until the bitter end" according to Christof Koch.

People

Pantheon has 190 people classified as British biologists born between 1545 and 1962. Of these 190, 17 (8.95%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living British biologists include Richard Henderson, Gregory Winter, and Michael Houghton. The most famous deceased British biologists include Charles Darwin, Alexander Fleming, and Rosalind Franklin.

Living British Biologists

Go to all RankingsRichard Henderson

1945 - Present

HPI: 73.98

Gregory Winter

1951 - Present

HPI: 72.70

Michael Houghton

1949 - Present

HPI: 72.03

Martin Evans

1941 - Present

HPI: 69.06

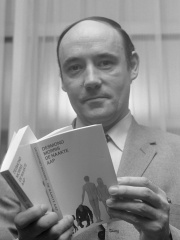

Desmond Morris

1928 - Present

HPI: 64.55

Jack W. Szostak

1952 - Present

HPI: 64.48

Matt Ridley

1958 - Present

HPI: 62.33

Alec Jeffreys

1950 - Present

HPI: 60.20

Susan Greenfield, Baroness Greenfield

1950 - Present

HPI: 60.16

Rupert Sheldrake

1942 - Present

HPI: 59.80

Sarah Gilbert

1962 - Present

HPI: 59.53

Paul Nurse

1949 - Present

HPI: 58.22

Deceased British Biologists

Go to all RankingsCharles Darwin

1809 - 1882

HPI: 91.48

Alexander Fleming

1881 - 1955

HPI: 84.76

Rosalind Franklin

1920 - 1958

HPI: 79.24

Robert Edwards

1925 - 2013

HPI: 78.39

Robert Brown

1773 - 1858

HPI: 78.23

Alfred Russel Wallace

1823 - 1913

HPI: 77.41

John Boyd Orr

1880 - 1971

HPI: 76.14

Thomas Henry Huxley

1825 - 1895

HPI: 75.76

John Sulston

1942 - 2018

HPI: 75.52

Francis Crick

1916 - 2004

HPI: 74.94

John Edward Gray

1800 - 1875

HPI: 74.46

Christian de Duve

1917 - 2013

HPI: 74.14

Overlapping Lives

Which Biologists were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Biologists since 1700.