The Most Famous

WRITERS from Iran

This page contains a list of the greatest Iranian Writers. The pantheon dataset contains 7,302 Writers, 63 of which were born in Iran. This makes Iran the birth place of the 22nd most number of Writers behind Netherlands, and Ireland.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Iranian Writers of all time. This list of famous Iranian Writers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Iranian Writers.

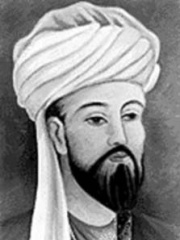

1. Abu Nuwas (762 - 814)

With an HPI of 82.59, Abu Nuwas is the most famous Iranian Writer. His biography has been translated into 142 different languages on wikipedia.

Abu Nuwas (أبو نواس, Abū Nuwās) (756-8 – c. 814) was a classical Arabic poet, and the foremost representative of the modern (muhdath) poetry that developed during the first years of the Abbasid Caliphate. He also entered the folkloric tradition, appearing several times in One Thousand and One Nights. Of mixed Arab and Persian heritage, he studied in Basra and al-Kufah, first under the poet Waliba ibn al-Hubab, and later under Khalaf al-Ahmar. He also studied the Qur'an, Hadith, and grammar. He earned the favour of the Abbasid caliphs Harun ar-Rashid and al-Amin. He is best known for his wine poetry, and Diwan, his collected volume of poetry that explored religion, pleasure, and homoeroticism.

2. Hafez (1325 - 1389)

With an HPI of 80.96, Hafez is the 2nd most famous Iranian Writer. His biography has been translated into 131 different languages.

Hafez Shirazi (1325–1390) was a Persian lyric poet whose collected works are regarded by many Iranians as one of the highest pinnacles of Persian literature. His works are often found in the homes of Persian speakers, who learn his poems by heart and use them as everyday proverbs and sayings. His life and poems have become the subjects of much analysis, commentary, and interpretation, influencing post-14th century Persian writing more than any other Persian author. Hafez is best known for his Divān, a collection of his surviving poems probably compiled after his death. His works can be described as "antinomian" and with the medieval use of the term "theosophical"; the term "theosophy" in the 13th and 14th centuries was used to indicate mystical work by "authors only inspired by the Islamic holy books" (as distinguished from theology). Hafez primarily wrote in the literary genre of lyric poetry or ghazals, which is the ideal style for expressing the ecstasy of divine inspiration in the mystical form of love poems. He was a Sufi. Themes of his ghazals include the beloved, faith and exposing hypocrisy. In his ghazals, he deals with love, wine and taverns, all presenting religious ecstasy and freedom from restraint, whether in actual worldly release or in the voice of the lover. His influence on Persian speakers appears in divination by his poems (Persian: فال حافظ, romanized: fāl-e hāfez, somewhat similar to the Roman tradition of Sortes Vergilianae) and in the frequent use of his poems in Persian traditional music, visual art and Persian calligraphy. His tomb is located in his birthplace of Shiraz. Adaptations, imitations, and translations of his poems exist in all major languages.

3. Ismail I (1487 - 1524)

With an HPI of 80.93, Ismail I is the 3rd most famous Iranian Writer. His biography has been translated into 71 different languages.

Ismail I (Persian: اسماعیل یکم, romanized: Ismāʿīl; 17 July 1487 – 23 May 1524) was the founder and first shah of Safavid Iran, ruling from 1501 until his death in 1524. His reign is one of the most vital in the history of Iran, and the Safavid era is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history. Under Ismail, Iran was unified under native rule for the first time since the Islamic conquest of the country eight-and-a-half centuries earlier. Ismail inherited leadership of the Safavid Sufi order from his brother as a child. His predecessors had transformed the religious order into a military movement supported by the Qizilbash (mainly Turkoman Shiite groups). The Safavids took control of the Azerbaijan region, and in 1501, Ismail was crowned as shah (king). In the following years, Ismail conquered the rest of Iran and other neighbouring territories. His expansion into Eastern Anatolia brought him into conflict with the Ottoman Empire. In 1514, the Ottomans decisively defeated the Safavids at the Battle of Chaldiran, which brought an end to Ismail's conquests. Ismail fell into depression and heavy drinking after this defeat and died in 1524. He was succeeded by his eldest son Tahmasp I. One of Ismail's first actions was the proclamation of the Twelver denomination of Shia Islam as the official religion of the Safavid state, marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam, which had major consequences for the ensuing history of Iran. He caused sectarian tensions in the Middle East when he destroyed the tombs of the Abbasid caliphs, the Sunni Imam Abu Hanifa, and the Sufi Muslim ascetic Abdul Qadir Gilani in 1508. The dynasty founded by Ismail I would rule for over two centuries, being one of the greatest Iranian empires and at its height being amongst the most powerful empires of its time, ruling all of present-day Iran, the Republic of Azerbaijan, Armenia, most of Georgia, the North Caucasus, and Iraq, as well as parts of modern-day Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. It also reasserted Iranian identity in large parts of Greater Iran. The legacy of the Safavid Empire was also the revival of Iran as an economic stronghold between the East and the West, the establishment of a bureaucratic state, its architectural innovations, and patronage for fine arts. Ismail I was also a prolific poet who under the pen name Khaṭāʾī (Arabic: خطائي, lit. 'the wrongful') contributed greatly to the literary development of the Azerbaijani language. He also contributed to Persian literature, though few of his Persian writings survive.

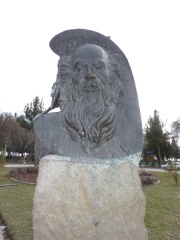

4. Ferdowsi (940 - 1020)

With an HPI of 77.11, Ferdowsi is the 4th most famous Iranian Writer. His biography has been translated into 101 different languages.

Ferdowsi (940-1025) was a Persian poet and the author of Shahnameh ("Book of Kings"), which is one of the world's longest epic poems created by a single poet, and the greatest epic of Persian-speaking countries. Ferdowsi is celebrated as one of the most influential figures of Persian literature and one of the greatest in the history of literature.

5. Mansur Al-Hallaj (858 - 922)

With an HPI of 76.84, Mansur Al-Hallaj is the 5th most famous Iranian Writer. His biography has been translated into 51 different languages.

Mansour al-Hallaj (Arabic: ابو المغيث الحسين بن منصور الحلاج, romanized: Abū 'l-Muġīth al-Ḥusayn ibn Manṣūr al-Ḥallāj) or Mansour Hallaj (Persian: منصور حلاج, romanized: Mansūr-e Hallāj) (c. 858 – 26 March 922) (Hijri c. 244 AH – 309 AH) was a mystic, poet, and teacher of Sufism. He was best known for his saying, "I am the Truth" ("Ana'l-Ḥaqq"), which many saw as a claim to divinity, while others interpreted it as an instance of annihilation of the ego, which allowed God to speak through him. Al-Hallaj gained a wide following as a preacher before he became implicated in power struggles of the Abbasid court and was executed after a long period of confinement on religious and political charges. Although most of his Sufi contemporaries disapproved of his actions, Hallaj later became a major figure in the Sufi tradition.

6. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201 - 1274)

With an HPI of 76.41, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi is the 6th most famous Iranian Writer. His biography has been translated into 63 different languages.

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Ṭūsī (1201 – 1274), also known as Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (Arabic: نصیر الدین الطوسی; Persian: نصیر الدین طوسی) or simply as (al-)Tusi, was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was a well published author, writing on subjects of math, engineering, prose, and mysticism. Additionally, al-Tusi made several scientific advancements. In astronomy, al-Tusi created very accurate tables of planetary motion, an updated planetary model, and critiques of Ptolemaic astronomy. He also made strides in logic, mathematics but especially trigonometry, biology, and chemistry. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi left behind a great legacy as well. Tusi is widely regarded as one of the greatest scientists of medieval Islam, since he is often considered the creator of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right. The Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) considered Tusi to be the greatest of the later Persian scholars. There is also reason to believe that he may have influenced Copernican heliocentrism.

7. Jami (1414 - 1492)

With an HPI of 76.34, Jami is the 7th most famous Iranian Writer. His biography has been translated into 65 different languages.

Nūr ad-Dīn 'Abd ar-Rahmān Jāmī (Persian: نورالدین عبدالرحمن جامی; 7 November 1414 – 9 November 1492), also known as Mawlanā Nūr al-Dīn 'Abd al-Rahmān or Abd-Al-Rahmān Nur-Al-Din Muhammad Dashti, or simply as Jami or Djāmī and in Turkey as Molla Cami, was a Persian Sunni poet who is known for his achievements as a prolific scholar and writer of mystical Sufi literature. He was primarily a prominent poet-theologian of the school of Ibn Arabi and a Khwājagānī Sũfī, recognized for his eloquence and for his analysis of the metaphysics of mercy. His most famous poetic works are Haft Awrang, Tuhfat al-Ahrar, Layla wa Majnun, Fatihat al-Shabab, Lawa'ih, Al-Durrah al-Fakhirah. Jami belonged to the Naqshbandi Sufi order.

8. Shams Tabrizi (1185 - 1248)

With an HPI of 75.75, Shams Tabrizi is the 8th most famous Iranian Writer. His biography has been translated into 37 different languages.

Shams Tabrīzī (1185–1248) was a Persian dervish and poet, He is referenced with great reverence and grief in Rumi's poetic collection, in particular Divan-i Shams-i Tabrīzī. Tradition holds that Shams taught Rumi in seclusion in Konya for a period of forty days, before fleeing for Damascus. The tomb of Shams-i Tabrīzī was recently nominated to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

9. Doris Lessing (1919 - 2013)

With an HPI of 75.37, Doris Lessing is the 9th most famous Iranian Writer. Her biography has been translated into 107 different languages.

Doris May Lessing (née Tayler; 22 October 1919 – 17 November 2013) was a British novelist – sometimes identified as Rhodesian early in her career – and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2007. Lessing was born to British parents in Persia, where she lived until she was 6 in 1925. Her family then moved to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), where she remained until moving to London, England, in 1949. Her novels include The Grass Is Singing (1950), the sequence of five novels collectively called Children of Violence (1952–1969), The Golden Notebook (1962), The Good Terrorist (1985), and five novels collectively known as Canopus in Argos: Archives (1979–1983). Lessing was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature. In awarding the prize, the Swedish Academy described her as "that epicist of the female experience, who with scepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilisation to scrutiny". Lessing was the oldest person ever to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, at age 87. In 2001 Lessing was awarded the David Cohen Prize for a lifetime's achievement in British literature. In 2008 The Times ranked her fifth on a list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".

10. Saadi Shirazi (1210 - 1291)

With an HPI of 75.10, Saadi Shirazi is the 10th most famous Iranian Writer. His biography has been translated into 80 different languages.

Saadi Shirazi (1210-1291) was an Iranian poet and prose writer of the late Islamic Golden Age and early Ilkhanate. He is recognized for the quality of his writings and for the depth of his social and moral thoughts. Saadi is widely recognized as one of the greatest poets of the classical literary tradition, earning him the nickname "The Master of Speech" or "The Wordsmith" (استاد سخن ostâd-e soxan) or simply "Master" (استاد ostâd) among Persian scholars. He has been quoted in the Western traditions as well. His book, Bustan has been ranked as one of the 100 greatest books of all time by The Guardian.

People

Pantheon has 63 people classified as Iranian writers born between 724 and 1983. Of these 63, 11 (17.46%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Iranian writers include Azar Nafisi, Kader Abdolah, and Cassandra Clare. The most famous deceased Iranian writers include Abu Nuwas, Hafez, and Ismail I. As of April 2024, 2 new Iranian writers have been added to Pantheon including Reza Aslan, and Armin Navabi.

Living Iranian Writers

Go to all RankingsAzar Nafisi

1955 - Present

HPI: 63.48

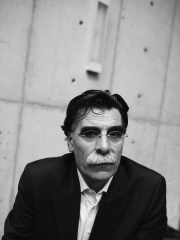

Kader Abdolah

1954 - Present

HPI: 60.74

Cassandra Clare

1973 - Present

HPI: 57.39

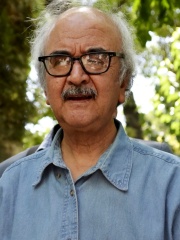

Mahmoud Dowlatabadi

1940 - Present

HPI: 54.95

Shahrnush Parsipur

1946 - Present

HPI: 54.39

Mohammad-Reza Shafiei Kadkani

1939 - Present

HPI: 53.47

Masih Alinejad

1976 - Present

HPI: 51.42

Marina Nemat

1965 - Present

HPI: 49.90

Roya Hakakian

1966 - Present

HPI: 46.60

Reza Aslan

1972 - Present

HPI: 43.21

Armin Navabi

1983 - Present

HPI: 35.88

Deceased Iranian Writers

Go to all RankingsAbu Nuwas

762 - 814

HPI: 82.59

Hafez

1325 - 1389

HPI: 80.96

Ismail I

1487 - 1524

HPI: 80.93

Ferdowsi

940 - 1020

HPI: 77.11

Mansur Al-Hallaj

858 - 922

HPI: 76.84

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

1201 - 1274

HPI: 76.41

Jami

1414 - 1492

HPI: 76.34

Shams Tabrizi

1185 - 1248

HPI: 75.75

Doris Lessing

1919 - 2013

HPI: 75.37

Saadi Shirazi

1210 - 1291

HPI: 75.10

Attar of Nishapur

1145 - 1220

HPI: 73.64

Magtymguly Pyragy

1733 - 1807

HPI: 70.86

Newly Added Iranian Writers (2025)

Go to all RankingsOverlapping Lives

Which Writers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Writers since 1700.