The Most Famous

RELIGIOUS FIGURES from Iran

This page contains a list of the greatest Iranian Religious Figures. The pantheon dataset contains 3,187 Religious Figures, 40 of which were born in Iran. This makes Iran the birth place of the 16th most number of Religious Figures behind Russia, and Iraq.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Iranian Religious Figures of all time. This list of famous Iranian Religious Figures is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Iranian Religious Figures.

1. Zoroaster (2000 BC - 2000 BC)

With an HPI of 85.42, Zoroaster is the most famous Iranian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 122 different languages on wikipedia.

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism. In the oldest Zoroastrian scriptures, the Gathas, which he is traditionally believed to have authored, he is described as a preacher and a poet-prophet. Some have claimed, with much scholarly controversy, to find his influence in Heraclitus, Plato, Pythagoras, and, perhaps less controversially, in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, particularly through concepts of cosmic dualism and personal morality. He spoke an Eastern Iranian language, named Avestan by scholars after the corpus of Zoroastrian religious texts written in that language. Based on this, it is tentative to place his homeland somewhere in the eastern regions of Greater Iran (perhaps in modern-day Afghanistan or Tajikistan), but his exact birthplace is uncertain. His life is traditionally dated to sometime around the 7th and 6th centuries BC; though most scholars, using linguistic and socio-cultural evidence, suggest a dating to somewhere in the 2nd millennium BC. Zoroastrianism eventually became Iran's most prominent religion from around the 6th century BC, enjoying official sanction during the time of the Sassanid Empire, until the 7th century AD, when the religion began to decline following the Arab-Muslim conquest of Iran. Zoroaster is credited with authorship of the Gathas as well as the Yasna Haptanghaiti, a series of hymns composed in Old Avestan that cover core Zoroastrian beliefs. Little is known about Zoroaster; most of his life is known only from these scant texts. By modern standards of historiography, no evidence can place him into a fixed period and the historicization surrounding him may be a part of a trend from before the 10th century AD that historicizes legends and myths. His name likely means "he who manages camels," though its etymology has multiple interpretations, and the Greek form "Zoroaster" stems from later transliterations. According to Zoroastrian tradition, Zoroaster was trained as a priest from a young age and, around age 30, experienced a divine revelation which introduced him to Ahura Mazda, the Wise Lord, and the dualism of truth (asha) versus deception (druj). He is said to have gained royal patronage under King Vishtaspa, spread his teachings, and founded a community, marrying three times and having six children. Zoroastrian texts portray his philosophy as emphasizing free will, ethical responsibility, and aligning with asha through good thoughts, words, and deeds.

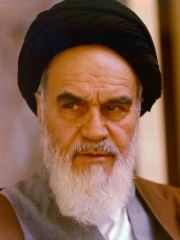

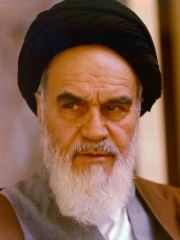

2. Ruhollah Khomeini (1902 - 1989)

With an HPI of 83.10, Ruhollah Khomeini is the 2nd most famous Iranian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 108 different languages.

Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini (17 May 1900 – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian cleric, politician, political theorist, and revolutionary who founded the Islamic Republic of Iran and served as its first supreme leader from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the main leader of the Iranian Revolution, which overthrew Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and transformed Iran into a theocratic Islamic republic. Born in Khomeyn, in what is now Iran's Markazi province, his father was murdered when Khomeini was two years old. He began studying the Quran and Arabic from a young age assisted by his relatives. Khomeini became a high ranking cleric in Twelver Shi'ism, an ayatollah, a marja' ("source of emulation"), a mujtahid or faqīh (an expert in fiqh), and author of more than 40 books. His opposition to the White Revolution resulted in his state-sponsored expulsion to Bursa in 1964. Nearly a year later, he moved to Najaf, where speeches he gave outlining his religiopolitical theory of Guardianship of the Jurist were compiled into Islamic Government. After the success of the Iranian Revolution, Khomeini served as the country's de facto head of state from February 1979 until his appointment as supreme leader in December of that same year. Khomeini was Time magazine's Man of the Year in 1979 for his international influence and in the next decade was described as the "virtual face of Shia Islam in Western popular culture". He was known for his support of the hostage takers during the Iran hostage crisis; his fatwa calling for the murder of British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie for Rushdie's description of Islamic prophet Muhammad in his novel The Satanic Verses, which Khomeini considered blasphemous; pursuing the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in the Iran–Iraq War; and for referring to the United States as the "Great Satan" and Israel as the "Little Satan". The subject of a pervasive cult of personality, Khomeini held the title Ayatollah and is officially known as Imam Khomeini inside Iran and by his supporters internationally. His state funeral was attended by up to 10 million people, one fifth of Iran's population, and is considered the second-largest funeral in history. In Iran, he is legally considered "inviolable"—insulting him is punishable with imprisonment; his gold-domed tomb in Tehran's Behesht-e Zahra cemetery has become a shrine for his adherents. His supporters view him as a champion of Islamic revival, independence, anti-imperialism, and resistance to foreign influence in Iran. Conversely, he has been criticized for anti-Western and antisemitic rhetoric, anti-democratic actions, human rights violations including the 1988 execution of thousands of Iranian political prisoners, and for using child soldiers extensively during the Iran–Iraq War for human wave attacks.

3. Bahá'u'lláh (1817 - 1892)

With an HPI of 81.34, Bahá'u'lláh is the 3rd most famous Iranian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 86 different languages.

Baháʼu'lláh (Persian: [bæhɒːʔolːɒːh], born Ḥusayn-ʻAlí; 12 November 1817 – 29 May 1892) was an Iranian religious leader who founded the Baháʼí Faith. He was born to an aristocratic family in Iran and was exiled due to his adherence to the messianic Bábism. In 1863, in Ottoman Iraq, he first announced his claim to a revelation from God and spent the rest of his life in further imprisonment in the Ottoman Empire. His teachings revolved around the principles of unity and religious renewal, ranging from moral and spiritual progress to world governance. Baháʼu'lláh was raised with no formal education but was well-read and devoutly religious. His family was considerably wealthy, and at the age of 22 he turned down a position in the government, instead managing family properties and donating time and money to charities. At the age of 27 he accepted the claim of the Báb and became one of the most outspoken supporters of the new religious movement which advocated, among other things, abrogation of Islamic law, which attracted heavy opposition. At the age of 33, during a governmental attempt to exterminate the movement, Baháʼu'lláh narrowly escaped death, his properties were confiscated, and he was banished from Iran. Just before leaving, while imprisoned in the Síyáh-Chál dungeon, Baháʼu'lláh claimed to receive revelations from God marking the beginning of his divine mission. After settling in Iraq, Baháʼu'lláh again attracted the ire of Iranian authorities, and they requested that the Ottoman government move him farther away. He spent months in Constantinople where the authorities became hostile to his religious claims and put him under house arrest in Edirne for four years, followed by two years of harsh confinement in the prison-city of Acre. His restrictions were gradually eased until his final years were spent in relative freedom in the area surrounding Acre. Baháʼu'lláh wrote at least 1,500 letters, some book-length, that have been translated into at least 802 languages. Some notable examples include the Hidden Words, the Kitáb-i-Íqán, and the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Some teachings are mystical and address the nature of God and the progress of the soul, while others address the needs of society, religious obligations of his followers, or the structure of Bahá’í institutions that would propagate the religion. He viewed humans as fundamentally spiritual beings and called upon individuals to develop divine virtues and further the material and spiritual advancement of society. Baháʼu'lláh died in 1892 near Acre. His burial place is a destination for pilgrimage by his followers, known as Bahá’ís, who now reside in 236 countries and territories and number between 5 and 8 million. Baháʼís regard Baháʼu'lláh as a Manifestation of God in succession to others like Buddha, Jesus, or Muhammad.

4. Esther (600 BC - 500 BC)

With an HPI of 81.25, Esther is the 4th most famous Iranian Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 60 different languages.

Esther (; Hebrew: אֶסְתֵּר, romanized: ʾEstēr), originally Hadassah (; Hebrew: הֲדַסָּה, romanized: haˈdasa), is the eponymous heroine of the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. According to the biblical narrative, which is set in the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian king Ahasuerus falls in love with Esther and marries her. His grand vizier Haman is offended by Esther's cousin and guardian Mordecai because of his refusal to bow before him; bowing in front of another person was a prominent gesture of respect in Persian society, but deemed unacceptable by Mordecai, who believes that a Jew should only express submissiveness to God. Consequently, Haman plots to have all of Persia's Jews killed, and eventually convinces Ahasuerus to permit him to do so. However, Esther foils the plan by revealing and decrying Haman's plans to Ahasuerus, who then has Haman executed and grants permission to the Jews to take up arms against their enemies; Esther is hailed for her courage and for working to save the Jews of Persia from eradication. The Book of Esther's story provides the traditional explanation for Purim, a celebratory Jewish holiday that is observed on the Hebrew date on which Haman's order was to go into effect, which is the day that the Jews killed their enemies after Esther exposed Haman's intentions to her husband; scholars have taken a mixed view as to the Book of Esther's historicity, with debates over its genre and the origins of Purim. Two related forms of the Book of Esther exist: a shorter Biblical Hebrew-sourced version found in Jewish and Protestant Bibles, and a longer Koine Greek-sourced version found in Catholic and Orthodox Bibles.

5. Abdul Qadir Gilani (1078 - 1166)

With an HPI of 79.64, Abdul Qadir Gilani is the 5th most famous Iranian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 52 different languages.

Abdul Qadir Gilani (c. 1077 or 1078 – c. 1166) was a Hanbali scholar, preacher, and Sufi mystic leader who was the eponym of the Qadiriyya, one of the oldest Sufi orders. He was born in c. 1077 or 1078 in the town of Na'if, Rezvanshahr in Gilan, Persia, and died in 1166 in Baghdad. His epithet, Gilani refers to his place of birth, Gilan, while the epithet, Baghdadi, referring to his residence and burial in Baghdad.

6. Hassan-i Sabbah (1050 - 1124)

With an HPI of 79.08, Hassan-i Sabbah is the 6th most famous Iranian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 45 different languages.

Hasan-i Sabbah also known as Hasan I of Alamut, was a religious and military leader, founder of the Nizari Ismai'li sect, Order of Assassins, as well as the Nizari Ismaili state, ruling from 1090 to 1124 AD. Alongside his role as a leader, Sabbah was a scholar of mathematics, most notably in geometry, as well as astronomy and philosophy, especially in epistemology. It is narrated that Hasan and the Persian polymath Omar Khayyam were close friends since their student years. He and each of the later Order of Assassins' leaders came to be known in the West as the "Old Man of the Mountain", a name given by Marco Polo that referenced the sect's possession of the commanding mountain fortress of Alamut Castle.

7. Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj (817 - 875)

With an HPI of 76.60, Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj is the 7th most famous Iranian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 59 different languages.

Abū al-Ḥusayn Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj ibn Muslim ibn Ward al-Qushayrī an-Naysābūrī (Arabic: أبو الحسين مسلم بن الحجاج بن مسلم بن وَرْد القشيري النيسابوري; after 815 – May 875 CE / 206 – 261 AH), commonly known as Imam Muslim, was an Islamic scholar from the city of Nishapur, particularly known as a muhaddith (scholar of hadith). His hadith collection, known as Sahih Muslim, is one of the six major hadith collections in Sunni Islam and is regarded as one of the two most authentic (sahih) collections, alongside Sahih al-Bukhari.

8. Báb (1819 - 1850)

With an HPI of 73.80, Báb is the 8th most famous Iranian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 75 different languages.

The Báb (born ʻAlí-Muḥammad; ; Persian: علیمحمد; 20 October 1819 – 9 July 1850) was an Iranian religious leader who founded Bábism, and is also one of the central figures of the Baháʼí Faith. The Báb gradually and progressively revealed his claim in his extensive writings to be a Manifestation of God, of a status as great as Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad, receiving revelations as profound as the Torah, Gospel, and Quran. This new revelation, he claimed, would release the creative energies and capacities necessary for the establishment of global unity and peace. He referred to himself by the traditional Muslim title "Báb" (meaning the gate) although it was apparent from the context that he intended by this term a spiritual claim very different from any which had previously been associated with it. He proclaimed that the central purpose of his mission was to prepare for the coming of a spiritual luminary greater than himself — the promised one of the world's great religions; he referred to this promised deliverer as "he whom God will make manifest". The Báb was the "gateway" to this messianic figure, whose message would be carried throughout the world. The Báb was born in Shiraz on 20 October 1819, to a family of sayyids of Husaynid lineage, most of whom were engaged in mercantile activities in Shiraz and Bushehr, He was a merchant from Shiraz in Qajar Iran who, in 1844 at the age of 25, began the Bábi Faith. In the next six years, the Báb composed numerous letters and books in which he abrogated Islamic laws and traditions, establishing a new religion and introducing a new social order focused on unity, love, and service to others. He encouraged the learning of arts and sciences, modernizing education, and improving the status of women. He introduced the concept of progressive revelation, highlighting the continuity and renewal of religion. He also emphasized ethics, independent investigation of truth, and human nobility. Additionally, he provided prescriptions to regulate marriage, divorce, and inheritance, and set forth rules for a future Bábí society, although these were never implemented. Throughout, the Báb always discussed his own revelation and laws in the context of the aforementioned promised figure. Unlike previous religions, which sporadically alluded to promised figures, the primary focus of the Bayán, the foundational text of the Bábí faith, was to prepare for the arrival of the promised one. The Báb was popular among the lower classes, the poor and the urban merchants, artisans, and some villagers. However, he faced opposition from the orthodox clergy and the government, which eventually executed him and thousands of his followers, who were known as Bábís. When the Báb was executed for apostasy, he was tied up in a public square in Tabriz and faced a firing squad of 750 rifles. Following the first volley, the Báb was discovered to be missing and later found and returned to the square. He was eventually killed by the second volley. Accounts differ on the details, but all agree that the first volley failed to kill him. This widely documented event increased interest in his message. His remains were secretly stored and transported until they were interred in 1909 into the shrine built for them by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá on the slopes of Mount Carmel. To Baháʼís, the Báb fills a similar role as Elijah in Judaism or John the Baptist in Christianity: a forerunner or founder of their own religion. Adherence to the Báb as a divine messenger has survived into modern times in the form of the 8-million-member Baháʼí Faith, whose founder, Baháʼu'lláh, claimed in 1863 to be the fulfillment of the Báb's prophecy. The majority of Bábí adherents converted and became Baháʼís by the end of the 19th century. The Baháʼís consider him a Manifestation of God, like Adam, Abraham, Moses, Zoroaster, Krishna, the Buddha, Jesus, Muhammad and Baháʼu'lláh.

9. Ibn Majah (824 - 886)

With an HPI of 72.73, Ibn Majah is the 9th most famous Iranian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 34 different languages.

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Yazīd Ibn Mājah al-Rabʿī al-Qazwīnī (Arabic: ابو عبد الله محمد بن يزيد بن ماجه الربعي القزويني; (b. 209/824, d. 273/887) commonly known as Ibn Mājah, was a medieval scholar of hadith of Persian origin. He compiled the last of Sunni Islam's six canonical hadith collections, Sunan Ibn Mājah.

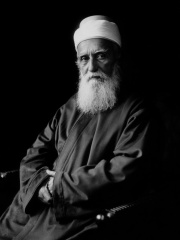

10. `Abdu'l-Bahá (1844 - 1921)

With an HPI of 71.89, `Abdu'l-Bahá is the 10th most famous Iranian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 44 different languages.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (; Persian: عبد البهاء, IPA: [ʔæbdolbæhɒːʔ];, 23 May 1844 – 28 November 1921), born ʻAbbás (Persian: عباس, IPA: [ʔæbːɒːs]), was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Bahá’í Faith, who designated him to be his successor and head of the Baháʼí Faith from 1892 until 1921. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was later cited as the last of three "central figures" of the religion, along with Baháʼu'lláh and the Báb, and his writings and authenticated talks are regarded as sources of Baháʼí sacred literature. He was born in Tehran to an aristocratic family. At the age of eight, his father was imprisoned during a government crackdown on the Bábí Faith and the family's possessions were looted, leaving them in virtual poverty. His father was exiled from their native Iran, and the family established their residence in Baghdad in Iraq, where they stayed for ten years. They were later called by the Ottoman state to Istanbul before entering another period of confinement in Edirne and finally the prison-city of ʻAkká (Acre). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá remained a prisoner there until the Young Turk Revolution freed him in 1908 at the age of 64. He then made several journeys to the West to spread the Baháʼí message beyond its middle-eastern roots, but the onset of World War I left him largely confined to Haifa from 1914 to 1918. Following the war, the openly hostile Ottoman authorities were replaced by the British Mandate over Palestine, during which time he was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his help in averting famine following the war. In 1892, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was appointed in his father's will to be his successor and head of the Baháʼí Faith. His Tablets of the Divine Plan galvanized Baháʼís in North America to spread the Baháʼí teachings to new territories, and his Will and Testament laid the foundation for the current Baháʼí administrative order. Many of his writings, prayers and letters are extant, and his discourses with the Western Baháʼís emphasize the growth of the religion by the late 1890s. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's given name was ʻAbbás. Depending on context, he would have gone by either Mírzá ʻAbbás (Persian) or ʻAbbás Effendi (Turkish), both of which are equivalent to the English Sir ʻAbbás. During most of his time as head of the Bahá'í Faith, he used and preferred the title of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá ("servant of Bahá", a reference to his father). He is commonly referred to in Baháʼí texts as "The Master".

People

Pantheon has 40 people classified as Iranian religious figures born between 2000 BC and 1960. Of these 40, 4 (10.00%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Iranian religious figures include Mordecai, Reza Hosseini Nassab, and Hossein Wahid Khorasani. The most famous deceased Iranian religious figures include Zoroaster, Ruhollah Khomeini, and Bahá'u'lláh. As of April 2024, 1 new Iranian religious figures have been added to Pantheon including Mostafa Pourmohammadi.

Living Iranian Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsMordecai

HPI: 70.14

Reza Hosseini Nassab

1960 - Present

HPI: 60.05

Hossein Wahid Khorasani

1921 - Present

HPI: 58.07

Mostafa Pourmohammadi

1960 - Present

HPI: 50.68

Deceased Iranian Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsZoroaster

2000 BC - 2000 BC

HPI: 85.42

Ruhollah Khomeini

1902 - 1989

HPI: 83.10

Bahá'u'lláh

1817 - 1892

HPI: 81.34

Esther

600 BC - 500 BC

HPI: 81.25

Abdul Qadir Gilani

1078 - 1166

HPI: 79.64

Hassan-i Sabbah

1050 - 1124

HPI: 79.08

Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj

817 - 875

HPI: 76.60

Báb

1819 - 1850

HPI: 73.80

Ibn Majah

824 - 886

HPI: 72.73

`Abdu'l-Bahá

1844 - 1921

HPI: 71.89

Sasan

200 - 300

HPI: 67.65

Anastasius of Persia

550 - 628

HPI: 67.53

Newly Added Iranian Religious Figures (2025)

Go to all RankingsOverlapping Lives

Which Religious Figures were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 12 most globally memorable Religious Figures since 1700.