The Most Famous

RACING DRIVERS from United Kingdom

This page contains a list of the greatest British Racing Drivers. The pantheon dataset contains 1,080 Racing Drivers, 205 of which were born in United Kingdom. This makes United Kingdom the birth place of the most number of Racing Drivers.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary British Racing Drivers of all time. This list of famous British Racing Drivers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of British Racing Drivers.

1. James Hunt (1947 - 1993)

With an HPI of 76.33, James Hunt is the most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 51 different languages on wikipedia.

James Simon Wallis Hunt (29 August 1947 – 15 June 1993) was a British racing driver and broadcaster who competed in Formula One from 1973 to 1979. Nicknamed "the Shunt", Hunt won the Formula One World Drivers' Championship in 1976 with McLaren, and won 10 Grands Prix across seven seasons. Born and raised in Surrey, Hunt began his racing career in touring cars before progressing to Formula Three in 1969, where he attracted the attention of Lord Hesketh, founder of Hesketh Racing. Hunt earned notoriety throughout his early career for his reckless and action-packed exploits on track, amongst his playboy lifestyle off it. He signed for Hesketh in 1973—driving a March 731 chassis designed by Harvey Postlethwaite—making his Formula One debut at the Monaco Grand Prix; he took podiums in his rookie season at the Dutch and United States Grands Prix. Hesketh entered their own 308 chassis in 1974, in which Hunt achieved several further podiums and won the non-championship BRDC International Trophy. Retaining his seat the following season, Hunt took his maiden victory with Hesketh at the Dutch Grand Prix, widely regarded as one of the greatest underdog victories in Formula One history. The team was left without sponsorship at the end of the season, leading Hunt to join McLaren for his 1976 campaign. Amidst a fierce title battle with Niki Lauda, Hunt won the World Drivers' Championship by a single point in his debut season with McLaren. He won several further races in 1977, dropping to fifth in the standings amidst reliability issues. After a winless 1978 season for McLaren, Hunt moved to Wolf in 1979 and retired after the Monaco Grand Prix, having achieved 10 race wins, 14 pole positions, eight fastest laps, and 23 podiums in Formula One. Upon retiring from motor racing, Hunt established a career as a commentator and pundit for the BBC, as well as a columnist for The Independent. Through Marlboro, he also mentored two-time World Drivers' Champion Mika Häkkinen. He died from a heart attack at his home in Wimbledon, aged 45.

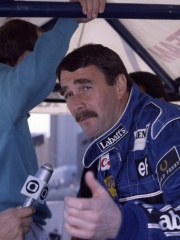

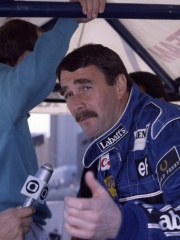

2. Nigel Mansell (b. 1953)

With an HPI of 72.62, Nigel Mansell is the 2nd most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 52 different languages.

Nigel Ernest James Mansell (; born 8 August 1953) is a British former racing driver who competed in Formula One from 1980 to 1995. Mansell won the Formula One World Drivers' Championship in 1992 with Williams, and won 31 Grands Prix across 15 seasons. In American open-wheel racing, Mansell won the IndyCar World Series in 1993 with Newman/Haas Racing, and remains the only driver to have simultaneously held both the World Drivers' Championship and the American open-wheel National Championship. Mansell's career in Formula One spanned 15 seasons, with his final two full seasons of top-level racing being spent in the CART series. Mansell was the reigning F1 champion when he moved to CART, becoming the first person to win the CART title in his debut season, and making him the only person to hold both the World Drivers' Championship and the American open-wheel National Championship simultaneously. Mansell is the second most successful British Formula One driver of all time in terms of race wins with 31 victories, behind Lewis Hamilton with 105 wins, and is eighth overall on the Formula One race winners list. He held the record for the most pole positions set in a single season, which was broken in 2011 by Sebastian Vettel. He also remains the last Formula One driver to win a Grand Prix over the age of 40, which was the 1994 Australian Grand Prix. Mansell raced in the Grand Prix Masters series in 2005, and won the championship title. He later signed a one-off race deal for the Scuderia Ecosse GT race team to drive their number 63 Ferrari F430 GT2 car at Silverstone on 6 May 2007. He has since competed in additional sports car races with his sons Leo and Greg, including the 2010 24 Hours of Le Mans, and was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 2005.

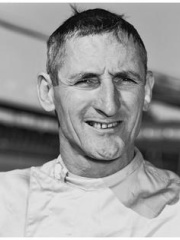

3. Ken Miles (1918 - 1966)

With an HPI of 72.47, Ken Miles is the 3rd most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 26 different languages.

Kenneth Henry Jarvis Miles (1 November 1918 – 17 August 1966) was an English sports car racing engineer and driver best known for his motorsport career in the U.S. and with American teams on the international scene. He is an inductee to the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America. As an automotive engineer, he is known for developing, along with driver and designer Carroll Shelby, the Ford GT40, the car that won the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1966, 1967, 1968, and 1969. Miles and Shelby's efforts at Le Mans were dramatized in the 2019 Oscar-winning film Ford v Ferrari.

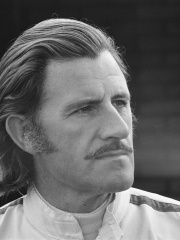

4. Jackie Stewart (b. 1939)

With an HPI of 72.02, Jackie Stewart is the 4th most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 60 different languages.

Sir John Young Stewart (born 11 June 1939) is a British former racing driver, broadcaster and motorsport executive from Scotland who competed in Formula One from 1965 to 1973. Nicknamed "the Flying Scot", Stewart won three Formula One World Drivers' Championship titles with Tyrrell, and—at the time of his retirement—held the records for most wins (27) and podium finishes (43). In addition to his three titles, Stewart finished as runner-up twice during his nine seasons in Formula One. He was the only British driver with three championships until Lewis Hamilton equalled him in 2015. Outside of Formula One, he narrowly missed out on a win at his first attempt at the Indianapolis 500 in 1966 and competed in the Can-Am series in 1970 and 1971. Between 1997 and 1999, in partnership with his son, Paul, he was team principal of the Stewart Grand Prix F1 racing team. After retiring from racing, Stewart was an ABC network television sports commentator for both auto racing, covering the Indianapolis 500 for over a decade, and for several summer Olympics covering many events, being a distinctive presence with his pronounced Scottish accent. Stewart also served as a television commercial spokesman for both the Ford Motor Company and Heineken beer. Stewart was instrumental in improving the safety of motor racing, campaigning for better medical facilities and track improvements at motor racing circuits. After John Surtees's death in 2017, he is the last surviving Formula One World Champion from the 1960s. He is also the oldest living Grand Prix winner.

5. Jim Clark (1936 - 1968)

With an HPI of 71.32, Jim Clark is the 5th most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 52 different languages.

James Clark (4 March 1936 – 7 April 1968) was a British racing driver from Scotland who competed in Formula One from 1960 to 1968. Clark won two Formula One World Drivers' Championship titles, in 1963 and 1965 with Lotus, and—at the time of his death—held the records for most wins (25), pole positions (33), and fastest laps (28), among others. In American open-wheel racing, Clark won the Indianapolis 500 in 1965 with Lotus, becoming the first non-American winner of the race in 49 years. Born in Fife and raised in the Scottish Borders, Clark started his racing career in road rallying and hillclimbing. By 1958, Clark had graduated to sports car racing in national competition with Border Reivers, racing the Jaguar D-Type and Porsche 356, where he attracted the attention of Lotus founder Colin Chapman. Driving a Lotus Elite, Clark finished second-in-class at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1959. Clark made his formula racing debut the following year in Formula Junior, winning the championship ahead of reigning seven-time Grand Prix motorcycle racing World Champion John Surtees. After immediately impressing in Formula Two, Clark was promoted to Formula One with Lotus for the remainder of the 1960 season alongside Surtees and Innes Ireland, making his debut at the Dutch Grand Prix and scoring his maiden podium four races later in Portugal; Clark finished third overall at Le Mans that year. Following multiple further podiums in 1961, Lotus fielded the highly-successful 25 chassis from 1962 onwards. Clark took his maiden win at the 1962 Belgian Grand Prix, achieving further wins at his home Grand Prix in Great Britain and in the United States, as he finished runner-up to career rival Graham Hill. After winning a then-record seven Grands Prix during his 1963 campaign, Clark won his maiden title, earning widespread acclaim for his performances. Despite winning the most races the following season, reliability issues with the Lotus 33 saw him fall to third in the standings. However, the same chassis would see Clark win again in 1965, as he took six victories in that season. Lotus then struggled to adapt to the 3-litre engine era, with Clark only able to win the United States Grand Prix during his second title defence. 1967 was more successful for Lotus under Cosworth power, with Clark taking four wins throughout the season. While leading the 1968 World Drivers' Championship, Clark died as a result of an accident during a Formula Two race at the Hockenheimring. Clark held the Formula One records for the most race wins until 1973, pole positions until 1989, and fastest laps also until 1989. He still holds several records in 2025, including the most grand slams (8). A versatile driver, Clark found success outside of formula racing in sports cars, touring cars, and American open-wheel racing. Clark was a champion in the British Saloon Car Championship, winning every race he entered in 1964, as well as in French and British Formula Two. He was a three-time champion of the Tasman Series, winning in 1965, 1967 and 1968, with a record 15 wins in 32 starts. In rallying, he entered the Rally of Great Britain in 1966. His successes in 1965—winning championships in Formula One, the Tasman Series, French Formula Two, and British Formula Two—make him the only driver in history to have won multiple championships in a single season alongside a World Drivers' Championship. Clark was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 1990.

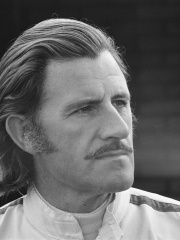

6. Graham Hill (1929 - 1975)

With an HPI of 70.66, Graham Hill is the 6th most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 51 different languages.

Norman Graham Hill (15 February 1929 – 29 November 1975) was a British racing driver, rower and motorsport executive, who competed in Formula One from 1958 to 1975. Nicknamed "Mr. Monaco", Hill won two Formula One World Drivers' Championship titles and—at the time of his retirement—held the record for most podium finishes (36); he won 14 Grands Prix across 18 seasons. In American open-wheel racing, Hill won the Indianapolis 500 in 1966 with Mecom. Upon winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1972 with Matra, Hill became the first—and to this date, only—driver to complete the Triple Crown of Motorsport. Born and raised in London, Hill studied engineering before completing national service in the Royal Navy. He was a member of London Rowing Club from 1952 to 1954, contesting twenty finals and stroking the London crew in the Grand Challenge Cup. He made his racing debut in Formula Three aged 25. He initially joined Lotus in Formula One as a mechanic, before earning a driving debut with the team at the 1958 Monaco Grand Prix and securing a full-time contract. After non-classified championship finishes in 1958 and 1959 with Lotus, Hill moved to BRM in 1960, scoring his maiden podium at the Dutch Grand Prix. BRM fielded the competitive P57 in 1962, with Hill taking his maiden victory at the season-opening Dutch Grand Prix and winning three further Grands Prix as he secured his maiden title, beating career rival Jim Clark and Bruce McLaren. He finished runner-up to Clark the following season, before losing the 1964 title by one point to John Surtees. Hill took multiple wins in 1965 as he finished runner-up to Clark once more in the standings. After a winless 1966 campaign, Hill returned to Lotus to partner Clark. Helping develop the Lotus 49 for the new Cosworth DFV engines, Hill struggled with reliability throughout 1967, with podiums in Monaco and the United States. Clark was killed after their 1–2 finish at the season opener in 1968, leaving Hill in a close title battle with Jackie Stewart, which Hill won at the final race of the season. In 1969, Hill became a five-time winner of the Monaco Grand Prix, a record he held for 24 years. During the United States Grand Prix, Hill was seriously injured in a crash, breaking both of his legs and ending his season prematurely. After recovering from his injuries, he returned as a privateer in 1970 before competing with Brabham for two further seasons, where he won the non-championship BRDC International Trophy in 1971. Hill founded and competed for Embassy Hill from 1973 to 1975, retiring from motor racing after the Monaco Grand Prix to focus on team ownership and supporting his protégé Tony Brise. In addition to his two championships, Hill achieved 14 race wins, 13 pole positions, ten fastest laps and 36 podiums in Formula One. Outside Formula One, Hill entered the 24 Hours of Le Mans ten times between 1958 and 1972, winning the latter alongside Henri Pescarolo in the Matra-Simca MS670. He also entered the Indianapolis 500 three times from 1966 to 1968, winning the Borg-Warner Trophy at his first attempt. Throughout his early years, Hill also competed in the British Saloon Car Championship, topping his class in 1963, and entered six seasons of the Tasman Series, finishing runner-up to Stewart in 1966. In November 1975, Hill and five other Embassy Hill executives, including Brise, were killed when the Piper PA-23 Aztec aircraft Hill was piloting crashed in low-visibility conditions in north London whilst returning from a test session for the Hill GH2 at the Circuit Paul Ricard. Embassy Hill subsequently shut down ahead of the 1976 season. Hill's son Damon went on to win the World Drivers' Championship in 1996, becoming the first father-and-son World Drivers' Champions. Hill was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 1990.

7. Alfonso de Portago (1928 - 1957)

With an HPI of 69.71, Alfonso de Portago is the 7th most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 27 different languages.

Alfonso Antonio Vicente Eduardo Ángel Blas Francisco de Borja Cabeza de Vaca y Leighton, 11th Marquess of Portago, GE (11 October 1928 – 12 May 1957), best known as Alfonso de Portago, was a Spanish aristocrat, racing and bobsleigh driver, jockey and pilot. Born in London to a prominent family in the peerage of Spain, de Portago was named after his godfather, King Alfonso XIII. His grandfather, the 9th Marquess of Portago, had been Minister of Public Instruction & Fine Arts and Mayor of Madrid, while his father, who was President of Puerta de Hierro and a prolific golfer, died of a heart attack while showering after a polo match. His mother, Olga Leighton, was an Irish nurse. At age 17, de Portago began displaying his flamboyant lifestyle by winning a $500 bet after flying a borrowed plane under London Tower Bridge. He twice rode the Grand National as "gentleman rider" and formed the first Spanish bobsleigh team with his cousins, finishing 4th in the 1956 Winter Olympics, missing the bronze medal by 0.14 seconds. In 1953, de Portago was introduced into the Scuderia Ferrari team, competing at the Carrera Panamericana, 1000 km Buenos Aires and several Grand Prix, including a win and second place at the 1956 Tour de France Automobile and 1956 British Grand Prix respectively. De Portago's promising career was cut short in May 1957 after his renowned Ferrari 335 S crashed near the village of Guidizzolo when a tyre burst while driving along a dead straight road at 150 mph (240 km/h) in the 1957 running of the Mille Miglia, killing Portago, his navigator, and nine spectators. The young age of the marquess, who was 28 at the time of his death, combined with his status as a sex symbol, caused a shock amongst many. Several tributes and landmarks were named after him, most notably the "Portago curve" at Jarama racetrack. The Marquess of Portago was seen by many as a true playboy of his time; "a tall, handsome and wealthy Spanish aristocrat who captured everybody's imagination". Gregor Grant famously said of him: "a man like Portago appears only once in a generation, and it would probably be more accurate to say only once in a lifetime. The fellow does everything fabulously well. Never mind the driving, the steeplechasing, the bobsledding, the athletic side of things, never mind being fluent in 4 languages. (...) He could be the best bridge player in the world if he cared to try, he could certainly be a great soldier, and I suspect he could be a fine writer".

8. John Surtees (1934 - 2017)

With an HPI of 69.11, John Surtees is the 8th most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 47 different languages.

John Norman Surtees (11 February 1934 – 10 March 2017) was a British racing driver and motorcycle road racer who competed in Grand Prix motorcycle racing from 1952 to 1960, and Formula One from 1960 to 1972. Surtees was a seven-time Grand Prix motorcycle World Champion, with four titles in the premier 500cc class with MV Agusta. Surtees won the Formula One World Drivers' Championship in 1964 with Ferrari, and remains the only driver to win World Championships on both two- and four-wheels; he won 38 motorcycle Grands Prix and six Formula One Grands Prix. On his way to become a seven-time Grand Prix motorcycle World Champion, Surtees won his first title in 1956, and followed with three consecutive doubles between 1958 and 1960, winning six World Championships in both the 500 and 350cc classes. Surtees then made the move to the pinnacle of four-wheeled motorsport, the Formula One World Championship, and in 1964 made motor racing history by becoming the Formula One World Champion. He founded the Surtees Racing Organisation team that competed as a constructor in Formula One, Formula 2 and Formula 5000 from 1970 to 1978. He was also the ambassador of the Racing Steps Foundation.

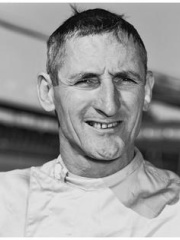

9. Mike Hawthorn (1929 - 1959)

With an HPI of 68.57, Mike Hawthorn is the 9th most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 48 different languages.

John Michael Hawthorn (10 April 1929 – 22 January 1959) was a British racing driver who competed in Formula One from 1952 to 1958. Hawthorn won the Formula One World Drivers' Championship in 1958 with Ferrari, and won three Grands Prix across seven seasons. In endurance racing, Hawthorn won both the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1955 with Jaguar. In 1958, Hawthorn became the first of 11 British Formula One World Champions, beating Stirling Moss to the title by one point. He announced his retirement upon his triumph, having been profoundly affected by the death of his teammate and friend Peter Collins two months earlier during the German Grand Prix. Three months after retiring, Hawthorn died in a road accident in Guildford, driving his Jaguar 3.4 Litre. The Hawthorn Memorial Trophy was established in his honour by the RAC in 1959, being awarded to the most successful British, or Commonwealth, driver in Formula One each year.

10. Damon Hill (b. 1960)

With an HPI of 67.97, Damon Hill is the 10th most famous British Racing Driver. His biography has been translated into 56 different languages.

Damon Graham Devereux Hill (born 17 September 1960) is a British former racing driver and broadcaster, who competed in Formula One from 1992 to 1999. Hill won the Formula One World Drivers' Championship in 1996 with Williams, and won 22 Grands Prix across eight seasons. Born and raised in London, Hill is the son of two-time Formula One World Champion Graham Hill, and, along with Nico Rosberg, one of two sons of a Formula One World Champion to also win the title. He started racing on motorbikes in 1981, and after minor success moved on to single-seater racing cars. Hill became a test driver for the Formula One title-winning Williams team in 1992. He was promoted to the Williams race team the following year after Riccardo Patrese's departure and took the first of his 22 victories at the 1993 Hungarian Grand Prix. During the mid-1990s, Hill was Michael Schumacher's main rival for the Formula One Drivers' Championship, which saw the two clash several times on and off the track. Their collision at the 1994 Australian Grand Prix gave Schumacher his first title by a single point. Hill became champion in 1996 with eight wins, but was dropped by Williams for the following season. He went on to drive for the less competitive Arrows and Jordan teams, and in 1998 gave Jordan their first win. Hill retired from racing after being dropped by Jordan following the 1999 season. In 2006, he became president of the British Racing Drivers' Club, succeeding Jackie Stewart. Hill stepped down from the position in 2011 and was succeeded by Derek Warwick. He presided over the securing of a 17-year contract for Silverstone to hold Formula One races, which enabled the circuit to see extensive renovation work. Hill formerly worked as part of the Sky Sports F1 broadcasting support team providing expert analysis during free practice sessions.

People

Pantheon has 205 people classified as British racing drivers born between 1900 and 2005. Of these 205, 92 (44.88%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living British racing drivers include Nigel Mansell, Jackie Stewart, and Damon Hill. The most famous deceased British racing drivers include James Hunt, Ken Miles, and Jim Clark. As of April 2024, 10 new British racing drivers have been added to Pantheon including Jann Mardenborough, Jonathan Rea, and Alister McRae.

Living British Racing Drivers

Go to all RankingsNigel Mansell

1953 - Present

HPI: 72.62

Jackie Stewart

1939 - Present

HPI: 72.02

Damon Hill

1960 - Present

HPI: 67.97

Lewis Hamilton

1985 - Present

HPI: 67.37

John Watson

1946 - Present

HPI: 61.73

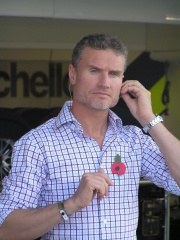

David Coulthard

1971 - Present

HPI: 61.55

Johnny Herbert

1964 - Present

HPI: 61.14

Guy Edwards

1942 - Present

HPI: 60.59

Derek Warwick

1954 - Present

HPI: 60.56

Martin Brundle

1959 - Present

HPI: 60.50

Divina Galica

1944 - Present

HPI: 60.33

Eddie Irvine

1965 - Present

HPI: 60.32

Deceased British Racing Drivers

Go to all RankingsJames Hunt

1947 - 1993

HPI: 76.33

Ken Miles

1918 - 1966

HPI: 72.47

Jim Clark

1936 - 1968

HPI: 71.32

Graham Hill

1929 - 1975

HPI: 70.66

Alfonso de Portago

1928 - 1957

HPI: 69.71

John Surtees

1934 - 2017

HPI: 69.11

Mike Hawthorn

1929 - 1959

HPI: 68.57

Stirling Moss

1929 - 2020

HPI: 67.96

Tony Brooks

1932 - 2022

HPI: 67.35

Tom Pryce

1949 - 1977

HPI: 64.32

Mike Hailwood

1940 - 1981

HPI: 63.85

Colin McRae

1968 - 2007

HPI: 63.06

Newly Added British Racing Drivers (2025)

Go to all RankingsJann Mardenborough

1991 - Present

HPI: 48.82

Jonathan Rea

1987 - Present

HPI: 47.16

Alister McRae

1970 - Present

HPI: 44.73

Ben Collins

1975 - Present

HPI: 43.49

Phil Mills

1963 - Present

HPI: 40.60

Jamie Green

1982 - Present

HPI: 38.07

Robert Huff

1979 - Present

HPI: 35.42

Phil Hanson

1999 - Present

HPI: 34.93

Katherine Legge

1980 - Present

HPI: 34.31

Alice Powell

1993 - Present

HPI: 26.94

Overlapping Lives

Which Racing Drivers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Racing Drivers since 1700.