The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Romania

This page contains a list of the greatest Romanian Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 188 of which were born in Romania. This makes Romania the birth place of the 21st most number of Politicians behind Iran, and Denmark.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Romanian Politicians of all time. This list of famous Romanian Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Romanian Politicians.

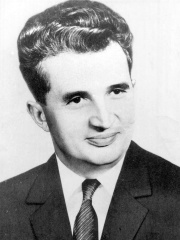

1. Nicolae Ceaușescu (1918 - 1989)

With an HPI of 85.32, Nicolae Ceaușescu is the most famous Romanian Politician. His biography has been translated into 99 different languages on wikipedia.

Nicolae Ceaușescu (Romanian: [ni.koˈla.e t͡ʃe̯a.uˈʃesku] ; 26 January [O.S. 13 January] 1918 – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian communist politician who led the Socialist Republic of Romania. He served as General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989 and as the first president of Romania from 1974 to 1989. Born in Scornicești, Ceaușescu joined the banned Romanian Communist Party in his teens and was repeatedly imprisoned under the pre-war and wartime regimes for his communist activism. After World War II, he rose through the party ranks under Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, the country’s Stalinist leader, whom he succeeded as general secretary. Upon taking power, Ceaușescu eased press censorship and condemned the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in his speech of 21 August 1968, which resulted in a surge in popularity. However, this period of liberalisation was brief, as his regime soon became totalitarian and was widely considered to be one of the most repressive in the Eastern Bloc. His secret police, the Securitate, was responsible for mass surveillance as well as severe repression and human rights abuses within the country, and controlled the media and press. Ceaușescu's attempts to implement policies that would lead to a significant growth of the population led to a growing number of illegal abortions and increased the number of orphans in state institutions. Economic mismanagement due to failed oil ventures during the 1970s led to very significant foreign debts for Romania. In 1982, Ceaușescu directed the government to export much of the country's agricultural and industrial production in an effort to repay these debts. His cult of personality experienced unprecedented elevation, followed by the deterioration of foreign relations, even with the Soviet Union. By the end of 1989, mounting discontent over the state of the nation and Ceaușescu’s totalitarian rule erupted into the Romanian Revolution. Ceaușescu perceived the demonstrations in Timișoara as a threat and ordered military forces to open fire on 17 December, causing many deaths and injuries. The demonstrations reached the capital Bucharest, forcing Ceaușescu and his wife Elena to flee in a helicopter, but they were soon captured after the armed forces turned on them. After being tried and convicted of economic sabotage and genocide, both were sentenced to death, and they were immediately executed by firing squad on 25 December, bringing an end to four decades of communist rule in Romania. The 21st century public polls have shown Romanians to be holding mostly positive view about his rule. A 2018 poll found 64% of people to have a good opinion of him.

2. Leo I the Thracian (401 - 474)

With an HPI of 81.08, Leo I the Thracian is the 2nd most famous Romanian Politician. His biography has been translated into 57 different languages.

Leo I (Ancient Greek: Λέων, romanized: Leōn; c. 401 – 18 January 474), also known as the Thracian (Latin: Thrax; Ancient Greek: ὁ Θρᾷξ), was Eastern Roman emperor from 457 to 474. He was a native of Dacia Aureliana near historic Thrace. He is sometimes surnamed with the epithet the Great (Latin: Magnus; Ancient Greek: ὁ Μέγας), probably to distinguish him from his young grandson and co-augustus Leo II (Ancient Greek: ὁ Μικρός, romanized: ho Mikrós, lit. 'the Small'). During his 17-year rule, he oversaw a number of ambitious political and military plans, aimed mostly at aiding the faltering Western Roman Empire and recovering its former territories. He is notable for being the first Eastern Emperor to legislate in Koine Greek rather than Late Latin. He is commemorated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, with his feast day on 20 January.

3. Michael I of Romania (1921 - 2017)

With an HPI of 79.19, Michael I of Romania is the 3rd most famous Romanian Politician. His biography has been translated into 57 different languages.

Michael I (Romanian: Mihai I Romanian: [miˈhaj ɨnˈtɨj] ; 25 October 1921 – 5 December 2017) was the last king of Romania, reigning from 20 July 1927 to 8 June 1930 and again from 6 September 1940 until his forced abdication on 30 December 1947. Shortly after Michael's birth, his father, Crown Prince Carol, had become involved in a controversial relationship with Magda Lupescu. In 1925, Carol was pressured to renounce his rights (in favour of his son Michael) to the throne and moved to Paris in exile with Lupescu. In July 1927, following the death of his grandfather Ferdinand I, Michael ascended the throne at age five, the youngest crowned head in Europe. As Michael was still a minor, a regency council was instituted, composed of his uncle Prince Nicolas, Patriarch Miron Cristea and Chief Justice Gheorghe Buzdugan. The council proved to be ineffective and, in 1930, Carol returned to Romania and replaced his son as monarch, reigning as Carol II. As a result, Michael returned to being heir apparent to the throne and was given the additional title of Grand Voievod of Alba-Iulia. Carol II was forced to abdicate in 1940, and Michael once again became king. Under the government led by the military dictator Ion Antonescu, Romania became aligned with Nazi Germany. In 1944, Michael participated in a coup against Antonescu, appointed Constantin Sănătescu as his replacement, and subsequently declared an alliance with the Allies. In March 1945, political pressures forced Michael to appoint a pro-Soviet government headed by Petru Groza. From August 1945 to January 1946, Michael went on a "royal strike" and unsuccessfully tried to oppose Groza's communist-controlled government by refusing to sign and endorse its decrees. In November 1947, Michael attended the wedding of his cousins, the future Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom and Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark in London. Shortly thereafter, on the morning of 30 December 1947, Groza met with Michael and compelled him to abdicate, while the monarchy was abolished. Michael was forced into exile, his properties confiscated, and his citizenship stripped. In 1948, he married Princess Anne of Bourbon-Parma, with whom he had five daughters. The couple eventually settled in Switzerland. Nicolae Ceaușescu's communist dictatorship was overthrown in December 1989, and the following year Michael attempted to return to Romania, only to be arrested and forced to leave upon arrival. In 1992, Michael was allowed to visit Romania for Easter, where he was greeted by huge crowds; a speech he gave from his hotel window drew an estimated one million people to Bucharest. Alarmed by Michael's popularity, the post-communist government of Ion Iliescu refused to allow him any further visits. In 1997, after Iliescu's defeat by Emil Constantinescu in the presidential election of the previous year, Michael's citizenship was restored and he was allowed to visit Romania again. Several confiscated properties, such as Peleș Castle and Săvârșin Castle, were eventually returned to his family.

4. Stephen Báthory (1533 - 1586)

With an HPI of 78.70, Stephen Báthory is the 4th most famous Romanian Politician. His biography has been translated into 56 different languages.

Stephen Báthory (Hungarian: Báthory István; Polish: Stefan Batory; Lithuanian: ; 27 September 1533 – 12 December 1586) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania as well as Prince of Transylvania (1576–1586), after previously being Voivode of Transylvania (1571–1576). The son of Stephen VIII Báthory and a member of the Hungarian Báthory noble family, Báthory was a ruler of Transylvania in the 1570s, defeating another challenger for that title, Gáspár Bekes. In 1576, Báthory became the husband of Queen Anna Jagiellon and the third elected king of Poland. He worked closely with chancellor Jan Zamoyski. The first years of his reign were focused on establishing power, defeating a fellow claimant to the throne, Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor, and quelling rebellions, most notably, the Gdańsk rebellion. He reigned only a decade, but is considered one of the most successful kings in Polish and Lithuanian history, particularly in the military realm. His signal achievement was his victorious campaign in Livonia against Russia in the middle part of his reign, in which he repulsed a Russian invasion of Commonwealth borderlands and secured a highly favorable treaty of peace (the Peace of Jam Zapolski).

5. Alaric I (376 - 410)

With an HPI of 78.28, Alaric I is the 5th most famous Romanian Politician. His biography has been translated into 75 different languages.

Alaric I (; Gothic: 𐌰𐌻𐌰𐍂𐌴𐌹𐌺𐍃, Alarīks lit.'ruler of all'; Latin: Alaricus; c. 370 – 411 AD) was the first king of the Visigoths, from 395 to 410. He rose to leadership of the Goths who came to occupy Moesia—territory acquired a couple of decades earlier by a combined force of Goths and Alans after the Battle of Adrianople. Alaric began his career under the Gothic soldier Gainas and later joined the Roman army. Once an ally of Rome under the Roman emperor Theodosius, Alaric helped defeat the Franks and other allies of a would-be Roman usurper. Despite losing many thousands of his men, he received little recognition from Rome and left the Roman army disappointed. After the death of Theodosius and the disintegration of the Roman armies in 395, he is described as king of the Visigoths. As the leader of the only effective field force remaining in the Balkans, he sought Roman legitimacy, never quite achieving a position acceptable to himself or to the Roman authorities. He operated mainly against the successive Western Roman regimes, and marched into Italy, where he died. He is responsible for the sack of Rome in 410; one of several notable events in the Western Roman Empire's eventual decline.

6. John Hunyadi (1407 - 1456)

With an HPI of 77.72, John Hunyadi is the 6th most famous Romanian Politician. His biography has been translated into 44 different languages.

John Hunyadi (Hungarian: Hunyadi János; Romanian: Ioan de Hunedoara; Croatian: Janko Hunjadi; Serbian: Сибињанин Јанко, romanized: Sibinjanin Janko; Ottoman Turkish: حونیادی یانوش, romanized: Hünyadi Yanoş; c. 1406 – 11 August 1456) was a leading Hungarian military and political figure during the 15th century, who served as regent of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1446 to 1453, under the minor Ladislaus V. According to most contemporary sources, he was the member of a noble family of Wallachian ancestry. Through his struggles against the Ottoman Empire, he earned for himself the nickname "Turk-buster" from his contemporaries. Due to his merits, he quickly received substantial land grants. By the time of his death, he was the owner of immense land areas, totaling approximately four million cadastral acres, which had no precedent before or after in the Kingdom of Hungary. His enormous wealth and his military and political weight were primarily directed towards the purposes of the Ottoman wars. Hunyadi mastered his military skills on the southern borderlands of the Kingdom of Hungary that were exposed to Ottoman attacks. Appointed Ban of Szörény in 1439, appointed Voivode of Transylvania, Counts of the Székelys and Chief Captain of Nándorfehérvár (now Belgrade) in 1441 and head of several southern counties of the Kingdom of Hungary, he assumed responsibility for the defense of the frontiers. He adopted the Hussite method of using wagons for military purposes. He employed professional soldiers, but also mobilized local peasantry against invaders. These innovations contributed to his earliest successes against the Ottoman troops who were plundering the southern marches in the early 1440s. In 1442, Hunyadi won four victories against the Ottomans, two of which were decisive. In March 1442, Hunyadi defeated Mezid Bey and the raiding Ottoman army at the Battle of Szeben in the south part of the Kingdom of Hungary in Transylvania. In September 1442, Hunyadi defeated a large Ottoman army of Beylerbey Şehabeddin, the Provincial Governor of Rumelia. This was the first time that a European army defeated such a large Ottoman force, composed not only of raiders, but of the provincial cavalry led by their own sanjak beys (governors) and accompanied by the formidable janissaries. Although defeated in the battle of Varna in 1444 and in the second battle of Kosovo in 1448, his successful "Long Campaign" across the Balkan Mountains in 1443–44 and defence of Belgrade (Nándorfehérvár) in 1456, against troops led personally by the sultan, established his reputation as a great general. The pope ordered that European churches ring their bells at noon to gather the faithful in prayer for those who were fighting. The bells of Christian churches are rung at noon to commemorate the Belgrade victory. John Hunyadi was also an eminent statesman. He actively took part in the civil war between the partisans of Wladislas I and the minor Ladislaus V, two claimants to the throne of Hungary in the early 1440s, on behalf of the former. He was popular among the lesser nobility, and in 1445 the Diet of Hungary appointed him one of the seven "Captains in Chief" responsible for the administration of state affairs until Ladislaus V (by that time unanimously accepted as king) came of age. The next Diet went even further, electing Hunyadi as sole regent with the title of governor. When he resigned from this office in 1452, the sovereign awarded him with the first hereditary title in the Kingdom of Hungary, (perpetual count of Beszterce/Bistrița). He had by this time become one of the wealthiest landowners in the kingdom, and preserved his influence in the Diet up until his death. This Athleta Christi (Christ's Champion), as Pope Pius II referred to him, died some three weeks after his triumph at Belgrade, falling to an epidemic that had broken out in the crusader camp. However, his victories over the Turks prevented them from invading the Kingdom of Hungary for more than 60 years. His fame was a decisive factor in the election of his son, Matthias Corvinus, as king by the Diet of 1457. Hunyadi is a popular historical figure among Hungarians, Romanians, Serbs, Bulgarians, Croats, and other nations of the region.

7. Ion Antonescu (1882 - 1946)

With an HPI of 77.28, Ion Antonescu is the 7th most famous Romanian Politician. His biography has been translated into 58 different languages.

Ion Antonescu (; Romanian: [iˈon antoˈnesku] ; 14 June [O.S. 2 June] 1882 – 1 June 1946) was a Romanian military officer and marshal who presided over two successive wartime dictatorships as Prime Minister and Conducător during most of World War II. Having been responsible for facilitating the Holocaust in Romania, he was overthrown in 1944, before being tried for war crimes and executed two years later in 1946. A Romanian Army career officer who made his name during the 1907 peasants' revolt and the World War I Romanian campaign, the antisemitic Antonescu sympathized with far-right and fascist politics. He was a military attaché to France and later Chief of the General Staff, briefly serving as Defence Minister in the National Christian cabinet of Octavian Goga as well as the subsequent First Cristea cabinet, in which he also served as Air and Marine Minister. During the late 1930s, his political stance brought him into conflict with King Carol II and led to his detainment. Antonescu rose to political prominence during the political crisis of 1940, and established the National Legionary State, an uneasy partnership with Horia Sima of the Iron Guard. After entering Romania into an alliance with Nazi Germany, he eliminated the Guard during the Legionary Rebellion of 1941. In addition to being Prime Minister, he served as his own Foreign Minister and Defence Minister. Soon after Romania joined the Axis in Operation Barbarossa, recovering Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, Antonescu also became Marshal of Romania. An atypical figure among Holocaust perpetrators, Antonescu enforced policies independently responsible for the deaths of as many as 400,000 people, most of them Bessarabian, Ukrainian and Romanian Jews, as well as Romanian Romani. The regime's complicity in the Holocaust combined pogroms and mass murders such as the Odessa massacre with ethnic cleansing, and systematic deportations to occupied Transnistria. The system in place was nevertheless characterized by singular inconsistencies, prioritizing plunder over killing, showing leniency toward most Jews in the Old Kingdom, and ultimately refusing to adopt the Final Solution. This was made possible by the fact that Romania, as a junior ally of Nazi Germany, was not occupied by the Wehrmacht and preserved a degree of political autonomy. Aerial attacks on Romania by the Allies in 1944 and heavy casualties on the Eastern Front prompted Antonescu to open peace negotiations with the Allies, which were inconclusive. On 23 August 1944, King Michael I led a coup d'état against Antonescu, who was arrested; after the war he was convicted of war crimes, and executed in June 1946. His involvement in the Holocaust was officially reasserted and condemned following the 2003 Wiesel Commission report.

8. Béla IV of Hungary (1206 - 1270)

With an HPI of 77.28, Béla IV of Hungary is the 8th most famous Romanian Politician. His biography has been translated into 50 different languages.

Béla IV (1206 – 3 May 1270) was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1235 and 1270, and Duke of Styria from 1254 to 1258. As the oldest son of King Andrew II, he was crowned upon the initiative of a group of influential noblemen in his father's lifetime in 1214. His father, who strongly opposed Béla's coronation, refused to give him a province to rule until 1220. In this year, Béla was appointed Duke of Slavonia, also with jurisdiction in Croatia and Dalmatia. Around the same time, Béla married Maria, a daughter of Theodore I Laskaris, Emperor of Nicaea. From 1226, he governed Transylvania as duke. He supported Christian missions among the pagan Cumans who dwelled in the plains to the east of his province. Some Cuman chieftains acknowledged his suzerainty and he adopted the title of King of Cumania in 1233. King Andrew died on 21 September 1235 and Béla succeeded him. He attempted to restore royal authority, which had diminished under his father. For this purpose, he revised his predecessors' land grants and reclaimed former royal estates, causing discontent among the noblemen and the prelates. The Mongols invaded Hungary and annihilated Béla's army in the Battle of Mohi on 11 April 1241. He escaped from the battlefield, but a Mongol detachment chased him from town to town as far as Trogir on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Although he survived the invasion, the Mongols devastated the country before their unexpected withdrawal in March 1242. Béla introduced radical reforms in order to prepare his kingdom for a second Mongol invasion. He allowed the barons and the prelates to erect stone fortresses and to set up their private armed forces. He promoted the development of fortified towns. During his reign, thousands of colonists arrived from the Holy Roman Empire, Poland and other neighboring regions to settle in the depopulated lands. Béla's efforts to rebuild his devastated country won him the epithet of "second founder of the state" (Hungarian: második honalapító). He set up a defensive alliance against the Mongols, which included Daniil Romanovich, Prince of Halych, Boleslaw the Chaste, Duke of Cracow and other Ruthenian and Polish princes. His allies supported him in occupying the Duchy of Styria in 1254, but it was lost to King Ottokar II of Bohemia six years later. During Béla's reign, a wide buffer zone—which included Bosnia, Barancs (Braničevo, Serbia) and other newly conquered regions—was established along the southern frontier of Hungary in the 1250s. Béla's relationship with his oldest son and heir, Stephen, became tense in the early 1260s, because the elderly king favored his daughter Anna and his youngest child, Béla, Duke of Slavonia. He was forced to cede the territories of the Kingdom of Hungary east of the river Danube to Stephen, which caused a civil war lasting until 1266. Nevertheless, Béla's family was famed for his piety: he died as a Franciscan tertiary, and the veneration of his three saintly daughters—Kunigunda, Yolanda, and Margaret—was confirmed by the Holy See.

9. Elena Ceaușescu (1916 - 1989)

With an HPI of 76.06, Elena Ceaușescu is the 9th most famous Romanian Politician. Her biography has been translated into 47 different languages.

Elena Ceaușescu (Romanian pronunciation: [eˈlena tʃe̯a.uˈʃesku]; born Lenuța Petrescu; (7 January 1916 [O.S. 25 December 1915] – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian communist politician who was the wife of Nicolae Ceaușescu, General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party and leader of the Socialist Republic of Romania. She was also the Deputy Prime Minister of Romania. Following the Romanian Revolution in 1989, she was executed alongside her husband on 25 December.

10. Radu cel Frumos (1438 - 1475)

With an HPI of 76.00, Radu cel Frumos is the 10th most famous Romanian Politician. His biography has been translated into 24 different languages.

Radu III of Wallachia, commonly called Radu the Handsome, Radu the Fair, or Radu the Beautiful (Romanian: Radu cel Frumos; Turkish: Radu Bey; c. 1438 – January 1475), was the younger brother of Vlad III (a.k.a. Vlad the Impaler) and prince of the principality of Wallachia. They were both sons of Vlad II Dracul and his wife, Princess Cneajna of Moldavia. In addition to Vlad III, Radu also had two older siblings, Mircea II and Vlad Călugărul, both of whom would also briefly rule Wallachia. In 1462, he defeated his brother, Vlad III, alongside Ottoman Empire sultan Mehmed II.

People

Pantheon has 188 people classified as Romanian politicians born between 220 and 1996. Of these 188, 60 (31.91%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Romanian politicians include Klaus Iohannis, Traian Băsescu, and László Tőkés. The most famous deceased Romanian politicians include Nicolae Ceaușescu, Leo I the Thracian, and Michael I of Romania. As of April 2024, 14 new Romanian politicians have been added to Pantheon including Călin Georgescu, Ilie Bolojan, and George Simion.

Living Romanian Politicians

Go to all RankingsKlaus Iohannis

1959 - Present

HPI: 72.08

Traian Băsescu

1951 - Present

HPI: 70.60

László Tőkés

1952 - Present

HPI: 65.73

Petre Roman

1946 - Present

HPI: 65.27

Călin Georgescu

1962 - Present

HPI: 64.81

Ilie Bolojan

1969 - Present

HPI: 62.80

Marcel Ciolacu

1967 - Present

HPI: 62.73

Crin Antonescu

1959 - Present

HPI: 62.25

Patriarch Daniel of Romania

1951 - Present

HPI: 61.21

Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu

1952 - Present

HPI: 61.00

Nicolae Ciucă

1967 - Present

HPI: 59.23

Theodor Stolojan

1943 - Present

HPI: 59.20

Deceased Romanian Politicians

Go to all RankingsNicolae Ceaușescu

1918 - 1989

HPI: 85.32

Leo I the Thracian

401 - 474

HPI: 81.08

Michael I of Romania

1921 - 2017

HPI: 79.19

Stephen Báthory

1533 - 1586

HPI: 78.70

Alaric I

376 - 410

HPI: 78.28

John Hunyadi

1407 - 1456

HPI: 77.72

Ion Antonescu

1882 - 1946

HPI: 77.28

Béla IV of Hungary

1206 - 1270

HPI: 77.28

Elena Ceaușescu

1916 - 1989

HPI: 76.06

Radu cel Frumos

1438 - 1475

HPI: 76.00

Vlad II Dracul

1395 - 1447

HPI: 75.27

Theodoric I

393 - 451

HPI: 75.26

Newly Added Romanian Politicians (2025)

Go to all RankingsCălin Georgescu

1962 - Present

HPI: 64.81

Ilie Bolojan

1969 - Present

HPI: 62.80

George Simion

1986 - Present

HPI: 58.24

Elena Lasconi

1972 - Present

HPI: 54.84

Gabriel Oprea

1961 - Present

HPI: 46.40

Roxana Mînzatu

1980 - Present

HPI: 46.37

Mihai Fifor

1970 - Present

HPI: 43.73

Roxana Maracineanu

1975 - Present

HPI: 39.96

Monica Iagăr

1973 - Present

HPI: 39.76

Andreea Chițu

1988 - Present

HPI: 37.55

Iuliana Popa

1996 - Present

HPI: 35.60

Alina Vuc

1993 - Present

HPI: 35.60

Overlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.