The Most Famous

PHILOSOPHERS from Austria

This page contains a list of the greatest Austrian Philosophers. The pantheon dataset contains 1,267 Philosophers, 17 of which were born in Austria. This makes Austria the birth place of the 15th most number of Philosophers behind Egypt, and Iran.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Austrian Philosophers of all time. This list of famous Austrian Philosophers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Austrian Philosophers.

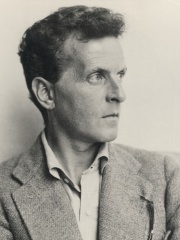

1. Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889 - 1951)

With an HPI of 83.27, Ludwig Wittgenstein is the most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 121 different languages on wikipedia.

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( VIT-gən-s(h)tyne; Austrian German: [ˈluːtvɪç ˈjoːsɛf ˈjoːhan ˈvɪtɡn̩ʃtaɪn]; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austro-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. From 1929 to 1947, Wittgenstein taught at the University of Cambridge. Despite his position, only one book of his philosophy was published during his life: the 75-page Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung (Logical-Philosophical Treatise, 1921), which appeared, together with an English translation, in 1922 under the Latin title Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. His only other published works were an article, "Some Remarks on Logical Form" (1929); a review of The Science of Logic, by P. Coffey; and a children's dictionary. His voluminous manuscripts were edited and published posthumously. The first and best-known of this posthumous series is the 1953 book Philosophical Investigations. A 1999 survey among American university and college teachers ranked the Investigations as the most important book of 20th-century philosophy, standing out as "the one crossover masterpiece in twentieth-century philosophy, appealing across diverse specializations and philosophical orientations". His philosophy is often divided into an early period, exemplified by the Tractatus, and a later period, articulated primarily in the Philosophical Investigations. The "early Wittgenstein" was concerned with the logical relationship between propositions and the world, and he believed that by providing an account of the logic underlying this relationship, he had solved all philosophical problems. The "later Wittgenstein", however, rejected many of the assumptions of the Tractatus, arguing that the meaning of words is best understood as their use within a given language game. More precisely, Wittgenstein wrote, "For a large class of cases of the employment of the word 'meaning'—though not for all—this word can be explained in this way: the meaning of a word is its use in the language." Born in Vienna into one of Europe's richest families, he inherited a fortune from his father in 1913. Before World War I, he "made a very generous financial bequest to a group of poets and artists chosen by Ludwig von Ficker, the editor of Der Brenner, from artists in need. These included [Georg] Trakl as well as Rainer Maria Rilke and the architect Adolf Loos", as well as the painter Oskar Kokoschka. "In autumn 1916, as his sister reported, 'Ludwig made a donation of a million crowns [equivalent to about $3.6 million in 2024] for the construction of a 30 cm mortar.'" Later, in a period of severe personal depression after World War I, he gave away his remaining fortune to his brothers and sisters. Three of his four older brothers died by separate acts of suicide. Wittgenstein left academia several times: serving as an officer on the front line during World War I, where he was decorated a number of times for his courage; teaching in schools in remote Austrian villages, where he encountered controversy for using sometimes violent corporal punishment on both girls and boys (see, for example, the Haidbauer incident), especially during mathematics classes; working during World War II as a hospital porter in London; and working as a hospital laboratory technician at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle upon Tyne.

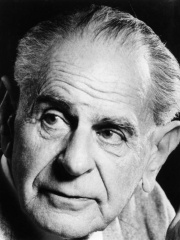

2. Karl Popper (1902 - 1994)

With an HPI of 81.86, Karl Popper is the 2nd most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 92 different languages.

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian–British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the classical inductivist views on the scientific method in favour of empirical falsification made possible by his falsifiability criterion, and for founding the Department of Philosophy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. According to Popper, a theory in the empirical sciences can never be proven, but it can be falsified, meaning that it can (and should) be scrutinised with decisive experiments. Popper was opposed to the classical justificationist account of knowledge, which he replaced with "the first non-justificational philosophy of criticism in the history of philosophy", namely critical rationalism. In political discourse, he is known for his vigorous defence of liberal democracy and the principles of social criticism that he believed made a flourishing open society possible. His political thought resides within the camp of Enlightenment rationalism and humanism. He was a dogged opponent of totalitarianism, communism, nationalism, fascism, and other kinds of (in Popper's view) reactionary and irrational ideas, and identified modern liberal democracies as the best-to-date embodiment of an open society.

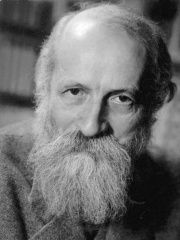

3. Martin Buber (1878 - 1965)

With an HPI of 76.75, Martin Buber is the 3rd most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 65 different languages.

Martin Buber (pronounced [ˈmaʁtiːn̩ ˈbuːbɐ] ; Hebrew: מרטין בובר, Yiddish: מארטין בובער; 8 February 1878 – 13 June 1965) was an Austrian-Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism centered on the distinction between the I–Thou relationship and the I–It relationship. Born in Vienna, Buber came from a family of observant Jews, but broke with Jewish custom to pursue secular studies in philosophy. He produced writings about Zionism and worked with various bodies within the Zionist movement extensively over a nearly 50-year period spanning his time in Europe and the Near East. In 1923, Buber wrote his famous essay on existence, Ich und Du (later translated into English as I and Thou), and in 1925 he began translating the Hebrew Bible into the German language. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature ten times, and the Nobel Peace Prize seven times.

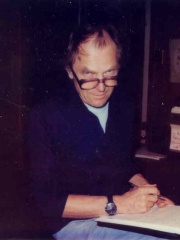

4. Paul Feyerabend (1924 - 1994)

With an HPI of 72.75, Paul Feyerabend is the 4th most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 45 different languages.

Paul Karl Feyerabend (; FY-ur-ah-bent; German: [ˈfaɪɐˌʔaːbm̩t]; January 13, 1924 – February 11, 1994) was an Austrian philosopher best known for his work in the philosophy of science. He started his academic career as lecturer in the philosophy of science at the University of Bristol (1955–1958); afterward, he moved to the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught for three decades (1958–1989). At various points in his life, he held joint appointments at the University College London (1967–1970), the London School of Economics (1967), the FU Berlin (1968), Yale University (1969), the University of Auckland (1972, 1975), the University of Sussex (1974), and the ETH Zurich (1980–1990). He gave lectures and lecture series at the University of Minnesota (1958–1962), Stanford University (1967), the University of Kassel (1977), and the University of Trento (1992). Feyerabend's most famous work is Against Method (1975), wherein he argues that there are no universally valid methodological rules for scientific inquiry. He also wrote on topics related to the politics of science in several essays and in his book Science in a Free Society (1978). Feyerabend's later works include Wissenschaft als Kunst (Science as Art) (1984), Farewell to Reason (1987), Three Dialogues on Knowledge (1991), and Conquest of Abundance (released posthumously in 1999), which collect essays from the 1970s until Feyerabend's death. The uncompleted draft of an earlier work was released posthumously in 2009 as Naturphilosophie and translated to English in 2016 as Philosophy of Nature. This work contains Feyerabend's reconstruction of the history of natural philosophy from the Homeric period until the mid-20th century. In these works and others, Feyerabend wrote about numerous issues at the interface between history and philosophy of science and ethics, ancient philosophy, philosophy of art, political philosophy, medicine, and physics. His final work was an autobiography, Killing Time, which he completed on his deathbed. Feyerabend's extensive correspondence and other materials from his Nachlass continue to be published. Feyerabend is recognized as one of the most important 20th-century philosophers of science. In a 2010 poll, he was ranked as the 8th-most significant philosopher of science. He is often mentioned alongside Thomas Kuhn, Imre Lakatos, and N. R. Hanson as a crucial figure in the historical turn in philosophy of science, and his work on scientific pluralism has been markedly influential on the Stanford School and on much contemporary philosophy of science. Feyerabend was also a significant figure in the sociology of scientific knowledge. His lectures were extremely well-attended, attracting international attention. His multifaceted personality is eloquently summarized in his obituary by Ian Hacking: "Humanists, in my old-fashioned sense, need to be part of both arts and sciences. Paul Feyerabend was a humanist. He was also fun." In line with this humanistic interpretation and the concerns apparent in his later work, the Paul K. Feyerabend Foundation was founded in 2006 in his honor. The Foundation "promotes the empowerment and wellbeing of disadvantaged human communities. By strengthening intra and inter-community solidarity, it strives to improve local capacities, promote the respect of human rights, and sustain cultural and biological diversity." In 1970, the Loyola University of Chicago awarded Feyerabend a Doctor of Humane Letters Degree honoris causa. Asteroid (22356) Feyerabend is named after him.

5. Josef Breuer (1842 - 1925)

With an HPI of 72.48, Josef Breuer is the 5th most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 31 different languages.

Josef Breuer ( BROY-ur; Austrian German: [ˈbrɔʏɐ]; 15 January 1842 – 20 June 1925) was an Austrian physician who made discoveries in neurophysiology, and whose work during the 1880s with his patient Bertha Pappenheim, known as Anna O., led to the development of the "cathartic method" (also referred to as the "talking cure") for psychiatric disorders. The method was a major initiatory factor for psychoanalysis, as developed by Breuer's friend and collaborator Sigmund Freud.

6. Ivan Illich (1926 - 2002)

With an HPI of 71.51, Ivan Illich is the 6th most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 41 different languages.

Ivan Dominic Illich ( iv-AHN IL-itch; German: [ˈiːvan ˈɪlɪtʃ]; 4 September 1926 – 2 December 2002) was an Austrian Catholic priest, theologian, philosopher, and social critic. His 1971 book Deschooling Society criticises modern society's institutional approach to education, an approach that demotivates and alienates individuals from the process of learning. His 1975 book Medical Nemesis, importing to the sociology of medicine the concept of medical harm, argues that industrialised society widely impairs quality of life by overmedicalising life, pathologizing normal conditions, creating false dependency, and limiting other more healthful solutions. Illich called himself "an errant pilgrim."

7. Otto Weininger (1880 - 1903)

With an HPI of 70.72, Otto Weininger is the 7th most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 38 different languages.

Otto Weininger (German: [ˈvaɪnɪŋɐ]; 3 April 1880 – 4 October 1903) was an Austrian philosopher who in 1903 published the book Geschlecht und Charakter (Sex and Character), which gained popularity after his suicide at the age of 23. Weininger had a strong influence on Ludwig Wittgenstein, August Strindberg, and, via his lesser-known work Über die letzten Dinge, on James Joyce.

8. Alfred Schütz (1899 - 1959)

With an HPI of 70.35, Alfred Schütz is the 8th most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 36 different languages.

Alfred Schutz (; born Alfred Schütz, German: [ʃʏts]; 1899–1959) was an Austrian philosopher and social phenomenologist whose work bridged sociological and phenomenological traditions. Schutz is gradually being recognized as one of the 20th century's leading philosophers of social science. He related Edmund Husserl's work to the social sciences, using it to develop the philosophical foundations of Max Weber's sociology, in his major work Phenomenology of the Social World. However, much of his influence arose from the publication of his Collected Papers in the 1960s.

9. Otto Neurath (1882 - 1945)

With an HPI of 69.31, Otto Neurath is the 9th most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 40 different languages.

Otto Karl Wilhelm Neurath (; Austrian German: [ˈɔtoː ˈnɔʏraːt]; 10 December 1882 – 22 December 1945) was an Austrian-born philosopher of science, sociologist, and political economist. He was also the inventor of the ISOTYPE method of pictorial statistics and an innovator in museum practice. Before he fled his native country in 1934, Neurath was one of the leading figures of the Vienna Circle.

10. Jean Améry (1912 - 1978)

With an HPI of 65.87, Jean Améry is the 10th most famous Austrian Philosopher. His biography has been translated into 24 different languages.

Jean Améry (31 October 1912 – 17 October 1978), born Hans Chaim Maier, was an Austrian-born essayist whose work was often informed by his experiences during World War II. His most celebrated work, At the Mind's Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities (1966), suggests that torture was "the essence" of the Third Reich. Other notable works included On Aging (1968) and On Suicide: A Discourse on Voluntary Death (1976). He adopted the pseudonym Jean Améry after 1945. Améry died by suicide in 1978. Formerly a philosophy and literature student in Vienna, Améry's participation in organized resistance against the Nazi occupation of Belgium resulted in his detainment and torture by the German Gestapo at Fort Breendonk, and several years of imprisonment in concentration camps. Améry survived internments in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, and was finally liberated at Bergen-Belsen in 1945. After the war he settled in Belgium.

People

Pantheon has 17 people classified as Austrian philosophers born between 1757 and 1926. Of these 17, none of them are still alive today. The most famous deceased Austrian philosophers include Ludwig Wittgenstein, Karl Popper, and Martin Buber.

Deceased Austrian Philosophers

Go to all RankingsLudwig Wittgenstein

1889 - 1951

HPI: 83.27

Karl Popper

1902 - 1994

HPI: 81.86

Martin Buber

1878 - 1965

HPI: 76.75

Paul Feyerabend

1924 - 1994

HPI: 72.75

Josef Breuer

1842 - 1925

HPI: 72.48

Ivan Illich

1926 - 2002

HPI: 71.51

Otto Weininger

1880 - 1903

HPI: 70.72

Alfred Schütz

1899 - 1959

HPI: 70.35

Otto Neurath

1882 - 1945

HPI: 69.31

Jean Améry

1912 - 1978

HPI: 65.87

Karl Leonhard Reinhold

1757 - 1823

HPI: 65.45

André Gorz

1923 - 2007

HPI: 64.16

Overlapping Lives

Which Philosophers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 16 most globally memorable Philosophers since 1700.