The Most Famous

COMPOSERS from Italy

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Italian Composers of all time. This list of famous Italian Composers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Italian Composers.

1. Antonio Vivaldi (1678 - 1741)

With an HPI of 91.00, Antonio Vivaldi is the most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 147 different languages on wikipedia.

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian composer, virtuoso violinist and impresario of Baroque music. Regarded as one of the greatest Baroque composers, Vivaldi's influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe, giving origin to many imitators and admirers. He pioneered many developments in orchestration, violin technique and programmatic music. He consolidated the emerging concerto form, especially the solo concerto, into a widely accepted and followed idiom. Vivaldi composed many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other musical instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than fifty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. Many of his compositions were written for the all-female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children in his native Venice. Vivaldi began studying for the Catholic priesthood at the age of 15 and was ordained at 25, but was given dispensation no longer to say public Masses due to a health problem. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for royal support. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died in poverty less than a year later. After almost two centuries of decline, Vivaldi's musical reputation underwent a revival in the early 20th century, with much scholarly research devoted to his work. Many of Vivaldi's compositions, once thought lost, have been rediscovered – some as recently as 2015. His music remains widely popular in the present day and is regularly played all over the world.

2. Giuseppe Verdi (1813 - 1901)

With an HPI of 89.28, Giuseppe Verdi is the 2nd most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 147 different languages.

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi ( VAIR-dee, Italian: [dʒuˈzɛppe ˈverdi]; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto, a small town in the modern province of Parma (at the time a department of the French Empire), to a family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the help of a local patron, Antonio Barezzi. Verdi came to dominate the Italian opera scene after the era of Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, and Gaetano Donizetti, whose works significantly influenced him. He was also strongly influenced by the French Grand opera style particularly by Giacomo Meyerbeer and Gaspare Spontini. In his early operas, Verdi demonstrated sympathy with the Risorgimento movement which sought the unification of Italy. He also served briefly as an elected politician. The chorus "Va, pensiero" from his early opera Nabucco (1842), and similar choruses in later operas, were much in the spirit of the unification movement, and the composer himself became esteemed as a representative of these ideals. An intensely private person, Verdi did not seek to ingratiate himself with popular movements. As he became professionally successful, he was able to reduce his operatic workload and sought to establish himself as a landowner in his native region. He found further fame with the three peaks of his 'middle period': Rigoletto (1851), Il trovatore and La traviata (both 1853). He surprised the musical world by returning, after his success with the opera Aida (1871), with three late masterpieces: his Requiem (1874), and the operas Otello (1887) and Falstaff (1893). Verdi's operas remain among the most popular in the repertoire. In 2013, the bicentenary of his birth was widely celebrated around the world with television and radio broadcasts and live performances.

3. Giacomo Puccini (1858 - 1924)

With an HPI of 85.72, Giacomo Puccini is the 3rd most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 123 different languages.

Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini (22 December 1858 – 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long line of composers, stemming from the late Baroque era. Though his early work was firmly rooted in traditional late-nineteenth-century Romantic Italian opera, it later developed in the realistic verismo style, of which he became one of the leading exponents. His most renowned works are La bohème (1896), Tosca (1900), Madama Butterfly (1904), and the unfinished Turandot (posthumously completed by Franco Alfano), all of which are among the most frequently performed and recorded in the entirety of the operatic repertoire.

4. Gioachino Rossini (1792 - 1868)

With an HPI of 83.90, Gioachino Rossini is the 4th most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 87 different languages.

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. He gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces and some sacred music. He set new standards for both comic and serious opera before retiring from large-scale composition while still in his thirties, at the height of his popularity. Born in Pesaro to parents who were both musicians (his father a trumpeter, his mother a singer), Rossini began to compose by the age of twelve and was educated at music school in Bologna. His first opera was performed in Venice in 1810 when he was 18 years old. In 1815 he was engaged to write operas and manage theatres in Naples. In the period 1810–1823, he wrote 34 operas for the Italian stage that were performed in Venice, Milan, Ferrara, Naples and elsewhere; this productivity necessitated an almost formulaic approach for some components (such as overtures) and a certain amount of self-borrowing. During this period he produced his most popular works, including the comic operas L'italiana in Algeri, Il barbiere di Siviglia (known in English as The Barber of Seville) and La Cenerentola, which brought to a peak the opera buffa tradition he inherited from masters such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Domenico Cimarosa and Giovanni Paisiello. He also composed opera seria works such as Tancredi, Otello and Semiramide. All of these attracted admiration for their innovation in melody, harmonic and instrumental colour, and dramatic form. In 1824 he was contracted by the Opéra in Paris, for which he produced an opera to celebrate the coronation of Charles X, Il viaggio a Reims (later cannibalised for his first opera in French, Le comte Ory), revisions of two of his Italian operas, Le siège de Corinthe and Moïse, and in 1829 his last opera, Guillaume Tell. Rossini's withdrawal from opera for the last 40 years of his life has never been fully explained; contributory factors may have been ill-health, the wealth his success had brought him, and the rise of spectacular grand opera under composers such as Giacomo Meyerbeer. From the early 1830s to 1855, when he left Paris and was based in Bologna, Rossini wrote relatively little. On his return to Paris in 1855 he became renowned for his musical salons on Saturdays, regularly attended by musicians and the artistic and fashionable circles of Paris, for which he wrote the entertaining pieces Péchés de vieillesse. Guests included Franz Liszt, Anton Rubinstein, Giuseppe Verdi, Meyerbeer, and Joseph Joachim. Rossini's last major composition was his Petite messe solennelle (1863).

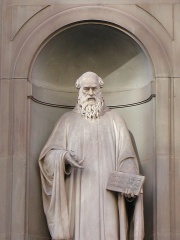

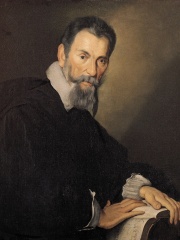

5. Claudio Monteverdi (1567 - 1643)

With an HPI of 83.41, Claudio Monteverdi is the 5th most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 76 different languages.

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both secular and sacred music, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is considered a crucial transitional figure between the Renaissance and Baroque periods of music history. Born in Cremona, where he undertook his first musical studies and compositions, Monteverdi developed his career first at the court of Mantua (c. 1590–1613) and then until his death in the Republic of Venice where he was maestro di cappella at the basilica of San Marco. His surviving letters give insight into the life of a professional musician in Italy of the period, including problems of income, patronage and politics. Much of Monteverdi's output, including many stage works, has been lost. His surviving music includes nine books of madrigals, large-scale religious works, such as his Vespro della Beata Vergine (Vespers for the Blessed Virgin) of 1610, and three complete operas. His opera L'Orfeo (1607) is the earliest of the genre still widely performed; towards the end of his life he wrote works for Venice, including Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria and L'incoronazione di Poppea. While he worked extensively in the tradition of earlier Renaissance polyphony, as evidenced in his madrigals, he undertook great developments in form and melody, and began to employ the basso continuo technique, distinctive of the Baroque. No stranger to controversy, he defended his sometimes novel techniques as elements of a seconda pratica, contrasting with the more orthodox earlier style which he termed the prima pratica. Largely forgotten during the eighteenth and much of the nineteenth centuries, his works enjoyed a rediscovery around the beginning of the twentieth century. He is now established both as a significant influence in European musical history and as a composer whose works are regularly performed and recorded.

6. Ennio Morricone (1928 - 2020)

With an HPI of 81.73, Ennio Morricone is the 6th most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 85 different languages.

Ennio Morricone ( EN-yoh MORR-ih-KOH-nee, -nay, Italian: [ˈɛnnjo morriˈkoːne]; 10 November 1928 – 6 July 2020) was an Italian composer, orchestrator, conductor, trumpeter, and pianist who wrote music in a wide range of styles. With more than 400 scores for cinema and television, as well as more than 100 classical works, Morricone is widely considered one of the most prolific and greatest film composers of all time. He received numerous accolades including two Academy Awards, three Grammy Awards, three Golden Globes, six BAFTAs, ten David di Donatello, eleven Nastro d'Argento, two European Film Awards, the Golden Lion Honorary Award, and the Polar Music Prize in 2010. His filmography includes more than 70 award-winning films, all of Sergio Leone's films since A Fistful of Dollars, all of Giuseppe Tornatore's films since Cinema Paradiso, Dario Argento's Animal Trilogy, as well as The Battle of Algiers (1966), 1900 (1976), La Cage aux Folles (1978), Le Professionnel (1981), The Thing (1982), The Key (1983) by Tinto Brass and Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1989). He received the Academy Award for Best Original Score nominations for Days of Heaven (1978), The Mission (1986), The Untouchables (1987), Bugsy (1991), Malèna (2000) and The Hateful Eight (2015), winning for the last. He won the Academy Honorary Award in 2007. His score to The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) is regarded as one of the most recognizable soundtracks in history. It was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2008. After playing the trumpet in jazz bands in the 1940s, Morricone became a studio arranger for RCA Victor and in 1955 started ghost writing for film and theatre. Throughout his career, he composed music for artists such as Paul Anka, Mina, Milva, Zucchero, and Andrea Bocelli. From 1960 to 1975, he gained international fame for composing music for Westerns and—with an estimated 10 million copies sold—Once Upon a Time in the West is one of the best-selling scores worldwide. From 1966 to 1980, he was a main member of Il Gruppo, one of the first experimental composers collectives. In 1969, he co-founded Forum Music Village, a prestigious recording studio. He continued to compose music for European productions, such as Marco Polo, La piovra, Nostromo, Fateless, Karol, and En mai, fais ce qu'il te plait. Morricone composed for Hollywood directors such as Don Siegel, Mike Nichols, Brian De Palma, Barry Levinson, William Friedkin, Oliver Stone, Warren Beatty, John Carpenter, and Quentin Tarantino. He has also worked with directors such as Bernardo Bertolucci, Mauro Bolognini, Tinto Brass, Giuliano Montaldo, Roland Joffé, Wolfgang Petersen, Roman Polanski, Henri Verneuil, Mario Bava, Lucio Fulci, Umberto Lenzi, Gillo Pontecorvo, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. His best-known compositions include "The Ecstasy of Gold", "Se telefonando", "Man with a Harmonica", "Here's to You", "Chi Mai", "Gabriel's Oboe", and "E Più Ti Penso". He has influenced many artists including Hans Zimmer, Danger Mouse, Dire Straits, Muse, Metallica, Fields of the Nephilim, and Radiohead.

7. Domenico Scarlatti (1685 - 1757)

With an HPI of 80.67, Domenico Scarlatti is the 7th most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 65 different languages.

Giuseppe Domenico Scarlatti (26 October 1685 – 23 July 1757) was an Italian composer. He is classified primarily as a Baroque composer chronologically, although his music was influential in the development of the Classical style. Like his renowned father Alessandro Scarlatti, he composed in a variety of musical forms, although today he is known mainly for his 555 keyboard sonatas. He spent much of his life in the service of the Portuguese and Spanish royal families.

8. Antonio Salieri (1750 - 1825)

With an HPI of 80.23, Antonio Salieri is the 8th most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 66 different languages.

Antonio Salieri (18 August 1750 – 7 May 1825) was an Italian composer and teacher of the classical period. He was born in Legnago, south of Verona, in the Republic of Venice, and spent his adult life and career as a subject of the Habsburg monarchy. Salieri was a pivotal figure in the development of late 18th-century opera. As a student of Florian Leopold Gassmann, and a protégé of Christoph Willibald Gluck, Salieri was a cosmopolitan composer who wrote operas in three languages. Salieri helped to develop and shape many of the features of operatic compositional vocabulary, and his music was a powerful influence on contemporary composers. Appointed the director of the Italian opera by the Habsburg court, a post he held from 1774 until 1792, Salieri dominated Italian-language opera in Vienna. During his career, he also spent time writing works for opera houses in Paris, Rome, and Venice, and his dramatic works were widely performed throughout Europe during his lifetime. As the Austrian imperial Kapellmeister from 1788 to 1824, he was responsible for music at the court chapel and attached school. Even as his works dropped from performance, and he wrote no new operas after 1804, he still remained one of the most important and sought-after teachers of his generation, and his influence was felt in every aspect of Vienna's musical life. Franz Liszt, Franz Schubert, Ludwig van Beethoven, Anton Eberl, Johann Nepomuk Hummel and Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart were among the most famous of his pupils. Salieri's music slowly disappeared from the repertoire between 1800 and 1868 and was rarely heard after that period until the revival of his fame in the late 20th century. This revival was partially due to the fictionalized depiction of Salieri in Peter Shaffer's play Amadeus (1979) and its 1984 film version. The death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1791 at the age of 35 was followed by rumors that he and Salieri had been bitter rivals, and that Salieri had poisoned the younger composer; however, this has been disproved because the symptoms displayed by Mozart's illness did not indicate poisoning and it is likely that they were, at least, mutually respectful peers. Salieri was greatly affected by the widespread public belief that he had contributed to Mozart's death, which he vehemently denied and contributed to his nervous breakdowns in later life.

9. Gaetano Donizetti (1797 - 1848)

With an HPI of 80.22, Gaetano Donizetti is the 9th most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 67 different languages.

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his over 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the bel canto opera style during the first half of the nineteenth century and a probable influence on other composers such as Giuseppe Verdi. Donizetti was born in Bergamo in Lombardy. At an early age he was taken up by Simon Mayr who enrolled him with a full scholarship in a school which he had set up. There he received detailed musical training. Mayr was instrumental in obtaining a place for Donizetti at the Bologna Academy, where, at the age of 19, he wrote his first one-act opera, the comedy Il Pigmalione, which may never have been performed during his lifetime. An offer in 1822 from Domenico Barbaja, the impresario of the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, which followed the composer's ninth opera, led to his move to Naples and his residency there until production of Caterina Cornaro in January 1844. In all, 51 of Donizetti's operas were presented in Naples. Before 1830, success came primarily with his comic operas, the serious ones failing to attract significant audiences. His first notable success came with an opera seria, Zoraida di Granata, which was presented in 1822 in Rome. In 1830, when Anna Bolena was first performed, Donizetti made a major impact on the Italian and international opera scene shifting the balance of success away from primarily comedic operas, although even after that date, his best-known works included comedies such as L'elisir d'amore (1832) and Don Pasquale (1843). Significant historical dramas did succeed; they included Lucia di Lammermoor (the first to have a libretto written by Salvadore Cammarano) given in Naples in 1835, and one of the most successful Neapolitan operas, Roberto Devereux in 1837. Up to that point, all of his operas had been set to Italian libretti. Donizetti found himself increasingly chafing against the censorship limitations in Italy (and especially in Naples). From about 1836, he became interested in working in Paris, where he saw greater freedom to choose subject matter, in addition to receiving larger fees and greater prestige. From 1838, beginning with an offer from the Paris Opéra for two new works, he spent much of the following 10 years in that city, and set several operas to French texts as well as overseeing staging of his Italian works. The first opera was a French version of the then-unperformed Poliuto which, in April 1840, was revised to become Les martyrs. Two new operas were also given in Paris at that time. Throughout the 1840s Donizetti moved between Naples, Rome, Paris, and Vienna, continuing to compose and stage his own operas as well as those of other composers. From around 1843, severe illness began to limit his activities. By early 1846 he was obliged to be confined to an institution for the mentally ill and, by late 1847, friends had him moved back to Bergamo, where he died in April 1848 in a state of mental derangement due to neurosyphilis.

10. Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632 - 1687)

With an HPI of 80.15, Jean-Baptiste Lully is the 10th most famous Italian Composer. His biography has been translated into 65 different languages.

Jean-Baptiste Lully born Giovanni Battista Lulli (28 or 29 November [O.S. 18 or 19 November] 1632 – 22 March 1687) was an Italian-French composer, dancer and instrumentalist, who is considered a master of the French Baroque music style. Best known for his operas, he spent most of his life working in the court of Louis XIV and became a French subject in 1661. He was a close friend of the playwright Molière, with whom he collaborated on numerous comédie-ballets, including L'Amour médecin, George Dandin ou le Mari confondu, Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, Psyché and his best known work, Le Bourgeois gentilhomme.

People

Pantheon has 176 people classified as Italian composers born between 991 and 1971. Of these 176, 3 (1.70%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Italian composers include Salvatore Sciarrino, Nicola Piovani, and Dario Marianelli. The most famous deceased Italian composers include Antonio Vivaldi, Giuseppe Verdi, and Giacomo Puccini.

Living Italian Composers

Go to all RankingsSalvatore Sciarrino

1947 - Present

HPI: 59.97

Nicola Piovani

1946 - Present

HPI: 58.39

Dario Marianelli

1963 - Present

HPI: 55.88

Deceased Italian Composers

Go to all RankingsAntonio Vivaldi

1678 - 1741

HPI: 91.00

Giuseppe Verdi

1813 - 1901

HPI: 89.28

Giacomo Puccini

1858 - 1924

HPI: 85.72

Gioachino Rossini

1792 - 1868

HPI: 83.90

Claudio Monteverdi

1567 - 1643

HPI: 83.41

Ennio Morricone

1928 - 2020

HPI: 81.73

Domenico Scarlatti

1685 - 1757

HPI: 80.67

Antonio Salieri

1750 - 1825

HPI: 80.23

Gaetano Donizetti

1797 - 1848

HPI: 80.22

Jean-Baptiste Lully

1632 - 1687

HPI: 80.15

Tomaso Albinoni

1671 - 1751

HPI: 79.90

Guido of Arezzo

991 - 1050

HPI: 79.78

Overlapping Lives

Which Composers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Composers since 1700.