The Most Famous

COMPOSERS from Germany

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary German Composers of all time. This list of famous German Composers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of German Composers.

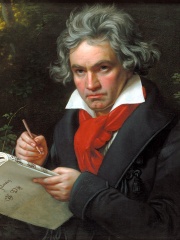

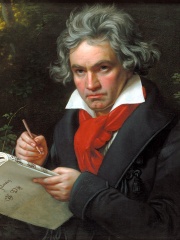

1. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 - 1827)

With an HPI of 96.89, Ludwig van Beethoven is the most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 210 different languages on wikipedia.

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 1770 – 26 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. One of the most revered figures in the history of Western music, his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire and span the transition from the Classical period to the Romantic era. Beethoven's early period, during which he forged his craft, is typically considered to have lasted until 1802. From 1802 to around 1812, his middle period showed an individual development from the styles of Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and is sometimes characterised as heroic. During this time, Beethoven began to grow increasingly deaf. In his late period, from 1812 to 1827, he extended his innovations in musical form and expression. Born in Bonn, Beethoven displayed his musical talent at a young age. He was initially taught intensively by his father, Johann van Beethoven, and later by Christian Gottlob Neefe. Under Neefe's tutelage in 1783, he published his first work, a set of keyboard variations. He found relief from a dysfunctional home life with the family of Helene von Breuning, whose children he loved, befriended, and taught piano. At age 21, he moved to Vienna, which subsequently became his base, and studied composition with Haydn. Beethoven then gained a reputation as a virtuoso pianist, and was soon patronised by Karl Alois, Prince Lichnowsky for compositions, which resulted in his three Opus 1 piano trios (the earliest works to which he accorded an opus number) in 1795. Beethoven's first major orchestral work, the First Symphony, premiered in 1800, and his first set of string quartets was published in 1801. Around 1798, Beethoven began experiencing symptoms of hearing loss; despite his advancing deafness during this period, he continued to conduct, premiering his Third and Fifth Symphonies in 1804 and 1808, respectively. His Violin Concerto appeared in 1806. His last piano concerto (No. 5, Op. 73, known as the Emperor), dedicated to his frequent patron Archduke Rudolf of Austria, premiered in 1811, without the composer as soloist. By 1815, Beethoven was nearly totally deaf and had ceased performing and seldom appeared in public. He described his health problems and his unfulfilled personal life in two letters, his "Heiligenstadt Testament" (1802) to his brothers and his unsent love letter to an unknown "Immortal Beloved" (1812). After 1810, increasingly less socially involved as his hearing loss worsened, Beethoven composed many of his most admired works, including his last three symphonies, mature chamber music and the late piano sonatas. His only opera, Fidelio, first performed in 1805, was extensively revised to its final version in 1814. He composed the Missa solemnis between 1819 and 1823 and his final Symphony, No. 9, the first major example of a choral symphony, between 1822 and 1824. His late string quartets, including the Grosse Fuge, of 1825–1826 are among his final achievements. After several months of illness, which left him bedridden, Beethoven died on 26 March 1827 at the age of 56.

2. Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750)

With an HPI of 92.78, Johann Sebastian Bach is the 2nd most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 217 different languages.

Johann Sebastian Bach (31 March [O.S. 21 March] 1685 – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his prolific output across a variety of instruments and forms, including the orchestral Brandenburg Concertos; solo instrumental works such as the cello suites and sonatas and partitas for solo violin; keyboard works such as the Goldberg Variations and The Well-Tempered Clavier; organ works such as the Schübler Chorales and the Toccata and Fugue in D minor; and choral works such as the St Matthew Passion and the Mass in B minor. Since the 19th-century Bach Revival, he has been widely regarded as one of the greatest composers in the history of Western music. The Bach family had already produced several composers when Johann Sebastian was born as the last child of a city musician, Johann Ambrosius, in Eisenach. After being orphaned at age 10, he lived for five years with his eldest brother, Johann Christoph, then continued his musical education in Lüneburg. In 1703 he returned to Thuringia, working as a musician for Protestant churches in Arnstadt and Mühlhausen. Around that time he also visited for longer periods the courts in Weimar, where he expanded his organ repertory, and the reformed court at Köthen, where he was mostly engaged with chamber music. By 1723 he was hired as Thomaskantor (cantor with related duties at St Thomas School) in Leipzig. There he composed music for the principal Lutheran churches of the city and Leipzig University's student ensemble, Collegium Musicum. In 1726 he began publishing his organ and other keyboard music. In Leipzig, as had happened during some of his earlier positions, he had difficult relations with his employer. This situation was somewhat remedied when his sovereign, Augustus III of Poland, granted him the title of court composer of the Elector of Saxony in 1736. In the last decades of his life, Bach reworked and extended many of his earlier compositions. He died due to complications following eye surgery in 1750 at the age of 65. Four of his twenty children, Wilhelm Friedemann, Carl Philipp Emanuel, Johann Christoph Friedrich, and Johann Christian, became composers. Bach enriched established German styles through his mastery of counterpoint, harmonic and motivic organisation, and his adaptation of rhythms, forms, and textures from abroad, particularly Italy and France. His compositions include hundreds of cantatas, both sacred and secular. He composed Latin church music, Passions, oratorios, and motets. He adopted Lutheran hymns, not only in his larger vocal works but also in such works as his four-part chorales and his sacred songs. Bach wrote extensively for organ and other keyboard instruments. He composed concertos, for instance for violin and for harpsichord, and suites, as chamber music as well as for orchestra. Many of his works use contrapuntal techniques like canon and fugue. Several decades after the end of his life, in the 18th century, Bach was still primarily known as an organist. Several biographies of Bach were published in the 19th century, and by the end of that century all of his known music had been printed. Dissemination of Bach scholarship continued through periodicals (and later also websites) devoted to him, other publications such as the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV, a numbered catalogue of his works), and new critical editions of his compositions. His music was further popularised by a multitude of arrangements, including the "Air on the G String" and "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring", and recordings, among them three different box sets of performances of his complete oeuvre marking the 250th anniversary of his death. By 2013, more than 150 recordings had been made of his Well-Tempered Clavier.

3. George Frideric Handel (1685 - 1759)

With an HPI of 88.95, George Frideric Handel is the 3rd most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 135 different languages.

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel ( HAN-dəl; baptised Georg Fried[e]rich Händel, German: [ˈɡeːɔʁk ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈhɛndl̩] ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well-known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concerti. Born in Halle, Handel spent his early life in Hamburg and Italy before settling in London in 1712, where he spent the bulk of his career and became a naturalised British subject in 1727. He was strongly influenced both by the middle-German polyphonic choral tradition and by composers of the Italian Baroque. In turn, Handel's music forms one of the peaks of the "high baroque" style, bringing Italian opera to its highest development, creating the genres of English oratorio and organ concerto, and introducing a new style into English church music. He is consistently recognised as one of the greatest composers of his age. Handel started three commercial opera companies to supply the English nobility with Italian opera. In 1737 he had a physical breakdown, changed direction creatively, addressed the middle class and made a transition to English choral works. After his success with Messiah (1742), he never composed an Italian opera again. His orchestral Water Music and Music for the Royal Fireworks remain steadfastly popular. One of his four coronation anthems, Zadok the Priest, has been performed at every British coronation since 1727. He died a respected and rich man in 1759, aged 74, and was given a state funeral at Westminster Abbey. Interest in Handel's music has grown since the mid-20th century. The musicologist Winton Dean wrote that "Handel was not only a great composer; he was a dramatic genius of the first order." His music was admired by Classical-era composers, especially Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven.

4. Richard Wagner (1813 - 1883)

With an HPI of 88.15, Richard Wagner is the 4th most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 158 different languages.

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( VAHG-nər; German: [ˈvɪlˌhɛlm ˈʁɪçaʁt ˈvaːɡnɐ] ; 22 May 1813 – 13 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor, best known for his operas—although his mature works are often referred to as music dramas. Unlike most composers, Wagner wrote both the libretti and the music for all of his stage works. He first achieved recognition with works in the Romantic tradition of Carl Maria von Weber and Giacomo Meyerbeer, but revolutionised the genre through his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk ("total work of art"), which sought to unite poetic, musical, visual, and dramatic elements. In this approach, the drama unfolds as a continuously sung narrative, with the music evolving organically from the text rather than alternating between arias and recitatives. Wagner outlined these ideas in a series of essays published between 1849 and 1852, most fully realising them in the first half of his four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung). Wagner's compositions, particularly in his later period, have complex textures, rich harmonies and orchestration, and elaborate leitmotifs—musical phrases associated with individual characters, places, ideas, or plot elements. His advances in musical language, such as extreme chromaticism and quickly shifting tonal centres, greatly influenced the development of classical music; his Tristan und Isolde is regarded as an important precursor to modernist music. Later in life, he softened his ideological stance against traditional operatic forms (e.g., arias, ensembles and choruses), reintroducing them into his last few stage works, including Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg) and Parsifal. To fully realise his artistic vision, Wagner had his own opera house built to his specifications: the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, which featured many innovations designed to immerse the audience in the drama. It hosted the premieres of The Ring and Parsifal, and remains entirely devoted to staging his mature works at the annual Bayreuth Festival. After Wagner’s death, his wife Cosima assumed leadership; it has since remained under the management of their descendants. Wagner's unorthodox operas, provocative essays, and contentious personal conduct engendered considerable controversy during his lifetime, and continue to do so. Declared a "genius" by some and a "disease" by others, his views on religion, politics, and society remain debated—most notably the extent to which his antisemitism finds expression in his stage and prose works. Despite this, his operas and music remain central to the repertoire of major opera houses and concert halls worldwide. His ideas can be traced across many art forms throughout the 20th century; his influence extended beyond composition into conducting, philosophy, literature, the visual arts, and theatre.

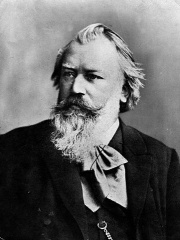

5. Johannes Brahms (1833 - 1897)

With an HPI of 85.79, Johannes Brahms is the 5th most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 129 different languages.

Johannes Brahms (; German: [joˈhanəs ˈbʁaːms] ; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. His music is noted for its rhythmic vitality and freer treatment of dissonance, often set within studied yet expressive contrapuntal textures. He adapted the traditional structures and techniques of a wide historical range of earlier composers. His œuvre includes four symphonies, four concertos, a Requiem, much chamber music, and hundreds of folk-song arrangements and Lieder, among other works for symphony orchestra, piano, organ, and choir. Born to a musical family in Hamburg, Brahms began composing and concertizing locally in his youth. He toured Central Europe as a pianist in his adulthood, premiering many of his own works and meeting Franz Liszt in Weimar. Brahms worked with Ede Reményi and Joseph Joachim, seeking Robert Schumann's approval through the latter. He gained both Robert and Clara Schumann's strong support and guidance. Brahms stayed with Clara in Düsseldorf, becoming devoted to her amid Robert's insanity and institutionalization. The two remained close, lifelong friends after Robert's death. Brahms never married, perhaps in an effort to focus on his work as a musician and scholar. He was a self-conscious, sometimes severely self-critical composer. Though innovative, his music was considered relatively conservative within the polarized context of the War of the Romantics, an affair in which Brahms regretted his public involvement. His compositions were largely successful, attracting a growing circle of supporters, friends, and musicians. Eduard Hanslick celebrated them polemically as absolute music, and Hans von Bülow even cast Brahms as the successor of Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven, an idea Richard Wagner mocked. Settling in Vienna, Brahms conducted the Singakademie and Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, programming the early and often "serious" music of his personal studies. He considered retiring from composition late in life but continued to write chamber music, especially for Richard Mühlfeld. Brahms' contributions and craftsmanship were admired by his contemporaries like Antonín Dvořák, whose music he enthusiastically supported, and a variety of later composers. Max Reger and Alexander Zemlinsky reconciled Brahms's and Wagner's often contrasted styles. So did Arnold Schoenberg, who emphasized Brahms's "progressive" side. He and Anton Webern were inspired by the intricate structural coherence of Brahms's music, including what Schoenberg termed its developing variation. It remains a staple of the concert repertoire, continuing to influence composers into the 21st century.

6. Robert Schumann (1810 - 1856)

With an HPI of 84.50, Robert Schumann is the 6th most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 102 different languages.

Robert Schumann (; German: [ˈʁoːbɛʁt ˈʃuːman]; 8 June 1810 – 29 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the early Romantic era. He composed in all the main musical genres of the time, writing for solo piano, voice and piano, chamber groups, orchestra, choir and the opera. His works typify the spirit of the Romantic era in German music. Schumann was born in Zwickau, Saxony, to an affluent middle-class family with no musical connections, and was initially unsure whether to pursue a career as a lawyer or to make a living as a pianist-composer. He studied law at the universities of Leipzig and Heidelberg but his main interests were music and Romantic literature. From 1829 he was a student of the piano teacher Friedrich Wieck, but his hopes for a career as a virtuoso pianist were frustrated by a worsening problem with his right hand, and he concentrated on composition. His early works were mainly piano pieces, including the large-scale Carnaval, Davidsbündlertänze (Dances of the League of David), Fantasiestücke (Fantasy Pieces), Kreisleriana and Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood) (1834–1838). He was a co-founder of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Musical Journal) in 1834 and edited it for ten years. In his writing for the journal and in his music he distinguished between two contrasting aspects of his personality, dubbing these alter egos "Florestan" for his impetuous self and "Eusebius" for his gentle poetic side. Despite the bitter opposition of Wieck, who did not regard his pupil as a suitable husband for her, Schumann married Wieck's daughter Clara in 1840. In the years immediately following their wedding Schumann composed prolifically, writing, first, songs and song‐cycles including Frauenliebe und Leben ("Woman's Love and Life") and Dichterliebe ("Poet's Love"). He turned his attention to orchestral music in 1841, completing the first of his four symphonies. In the following year he concentrated on chamber music, writing three string quartets, a Piano Quintet and a Piano Quartet. During the rest of the 1840s, between bouts of mental and physical ill health, he composed a variety of piano and other pieces and went with his wife on concert tours in Europe. His only opera, Genoveva (1850), was not a success and has seldom been staged since. Schumann and his family moved to Düsseldorf in 1850 in the hope that his appointment as the city's director of music would provide financial security, but his shyness and mental instability made it difficult for him to work with his orchestra and he had to resign after three years. In 1853 the Schumanns met the twenty-year-old Johannes Brahms, whom Schumann praised in an article in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. The following year Schumann's always-precarious mental health deteriorated gravely. He threw himself into the River Rhine but was rescued and taken to a private sanatorium near Bonn, where he lived for more than two years, dying there at the age of 46. During his lifetime Schumann was recognised for his piano music – often subtly programmatic – and his songs. His other works were less generally admired, and for many years there was a widespread belief that those from his later years lacked the inspiration of his early music. More recently this view has been less prevalent, but it is still his piano works and songs from the 1830s and 1840s on which his reputation is primarily based. He had considerable influence in the nineteenth century and beyond. In the German-speaking world the composers Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Arnold Schoenberg and more recently Wolfgang Rihm have been inspired by his music, as were French composers such as Georges Bizet, Gabriel Fauré, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Schumann was also a major influence on the Russian school of composers, including Anton Rubinstein and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

7. Felix Mendelssohn (1809 - 1847)

With an HPI of 83.51, Felix Mendelssohn is the 7th most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 103 different languages.

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 1809 – 4 November 1847), widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include symphonies, concertos, piano music, organ music and chamber music. His best-known works include the overture and incidental music for A Midsummer Night's Dream (which includes his "Wedding March"), the Italian and Scottish Symphonies, the oratorios St. Paul and Elijah, the Hebrides Overture, the mature Violin Concerto, the String Octet, and the melody used in the Christmas carol "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing". Mendelssohn's Songs Without Words are his most famous solo piano compositions. Mendelssohn's grandfather was the Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, but Felix was initially raised without religion until he was baptised aged seven into the Reformed Christian church. He was recognised early as a musical prodigy, but his parents were cautious and did not seek to capitalise on his talent. His sister Fanny Mendelssohn received a similar musical education and was a talented composer and pianist in her own right; some of her early songs were published under her brother's name and her Easter Sonata was for a time mistakenly attributed to him after being lost and rediscovered in the 1970s. Mendelssohn enjoyed early success in Germany, and revived interest in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, notably with his performance of the St Matthew Passion in 1829. He became well received in his travels throughout Europe as a composer, conductor and soloist; his ten visits to Britain – during which many of his major works were premiered – form an important part of his adult career. His essentially conservative musical tastes set him apart from more adventurous musical contemporaries, such as Franz Liszt, Richard Wagner, Charles-Valentin Alkan and Hector Berlioz. The Leipzig Conservatory, which he founded, became a bastion of this anti-radical outlook. After a long period of relative denigration due to changing musical tastes and antisemitism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his creative originality has been re-evaluated. He is now among the most popular composers of the Romantic era.

8. Jacques Offenbach (1819 - 1880)

With an HPI of 82.37, Jacques Offenbach is the 8th most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 92 different languages.

Jacques Offenbach (; 20 June 1819 – 5 October 1880) was a German-born French composer, cellist and impresario. He is remembered for his nearly 100 operettas of the 1850s to the 1870s, and his uncompleted opera The Tales of Hoffmann. He was a powerful influence on later composers of the operetta genre, particularly Franz von Suppé, Johann Strauss II and Arthur Sullivan. His best-known works were continually revived during the 20th century, and many of his operettas continue to be staged in the 21st. The Tales of Hoffmann remains part of the standard opera repertory. Born in Cologne, Kingdom of Prussia, the son of a synagogue cantor, Offenbach showed early musical talent. At the age of 14, he was accepted as a student at the Paris Conservatoire; he found academic study unfulfilling and left after a year, but remained in Paris. From 1835 to 1855 he earned his living as a cellist, achieving international fame, and as a conductor. His ambition, however, was to compose comic pieces for the musical theatre. Finding the management of Paris's Opéra-Comique company uninterested in staging his works, in 1855 he leased a small theatre in the Champs-Élysées. There, during the next three years, he presented a series of more than two dozen of his own small-scale pieces, many of which became popular. In 1858 Offenbach produced his first full-length operetta, Orphée aux enfers ("Orpheus in the Underworld"), with its celebrated can-can; the work was exceptionally well received and has remained his most played. During the 1860s, he produced at least eighteen full-length operettas, as well as more one-act pieces. His works from this period include La belle Hélène (1864), La Vie parisienne (1866), La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867) and La Périchole (1868). The risqué humour (often about sexual intrigue) and mostly gentle satiric barbs in these pieces, together with Offenbach's facility for melody, made them internationally known, and translated versions were successful in Vienna, London, elsewhere in Europe and in the US. Offenbach became associated with the Second French Empire of Napoleon III: the emperor and his court were genially satirised in many of Offenbach's operettas, and Napoleon personally granted him French citizenship and the Légion d'honneur. With the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, and the fall of the empire, Offenbach found himself out of favour in Paris because of his imperial connections and his German birth. He remained successful in Vienna, London and New York. He re-established himself in Paris during the 1870s, with revivals of some of his earlier favourites and a series of new works, and undertook a popular US tour. In his last years he strove to finish The Tales of Hoffmann, but died before the premiere of the opera, which has entered the standard repertory in versions completed or edited by other musicians.

9. Richard Strauss (1864 - 1949)

With an HPI of 80.88, Richard Strauss is the 9th most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 78 different languages.

Richard Georg Strauss (; German: [ˈʁɪçaʁt ˈʃtʁaʊs] ; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer and conductor known for his tone poems and operas. A leading figure of the late Romantic and early Modern era, and a successor to Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt, he combined, along with his friend Gustav Mahler, subtleties of orchestration with an advanced harmonic style. His compositional output began in 1870 when he was just six years old and lasted until his death nearly eighty years later. His first tone poem to achieve wide acclaim was Don Juan, and this was followed by other lauded works of this kind, including Death and Transfiguration, Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, Also sprach Zarathustra, Don Quixote, Ein Heldenleben, Symphonia Domestica, and An Alpine Symphony. His first opera to achieve international fame was Salome, which used a libretto by Hedwig Lachmann that was a German translation of the French play Salomé by Oscar Wilde. This was followed by several critically acclaimed operas with librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Elektra, Der Rosenkavalier, Ariadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten, Die ägyptische Helena, and Arabella. His last operas, Daphne, Friedenstag, Die Liebe der Danae and Capriccio used libretti written by Joseph Gregor, the Viennese theatre historian. Other well-known works by Strauss include two symphonies, lieder (especially the Four Last Songs), the Violin Concerto in D minor, the Horn Concerto No. 1, Horn Concerto No. 2, his Oboe Concerto and other instrumental works such as Metamorphosen. A prominent conductor in Western Europe and the Americas, Strauss enjoyed quasi-celebrity status as his compositions became standards of orchestral and operatic repertoire. He was chiefly admired for his interpretations of the works of Liszt, Mozart, and Wagner in addition to his own works. A conducting disciple of Hans von Bülow, Strauss began his conducting career as Bülow's assistant with the Meiningen Court Orchestra in 1883. After Bülow resigned in 1885, Strauss served as that orchestra's primary conductor for five months before being appointed to the conducting staff of the Bavarian State Opera where he worked as third conductor from 1886 to 1889. He then served as principal conductor of the Deutsches Nationaltheater und Staatskapelle Weimar from 1889 to 1894. In 1894 he made his conducting debut at the Bayreuth Festival, conducting Wagner's Tannhäuser with his wife, soprano Pauline de Ahna, singing Elisabeth. He then returned to the Bavarian State Opera, this time as principal conductor, from 1894 to 1898, after which he was principal conductor of the Berlin State Opera from 1898 to 1913. From 1919 to 1924 he was principal conductor of the Vienna State Opera, and in 1920 he co-founded the Salzburg Festival. In addition to these posts, Strauss was a frequent guest conductor in opera houses and with orchestras internationally. In 1933 Strauss was appointed to two important positions in the musical life of Nazi Germany: head of the Reichsmusikkammer and principal conductor of the Bayreuth Festival. The latter role he accepted after conductor Arturo Toscanini had resigned from the position in protest against the Nazi Party. These positions have led some to criticize Strauss for his seeming collaboration with the Nazis. However, Strauss's daughter-in-law, Alice Grab Strauss (née von Hermannswörth), was Jewish, and much of his apparent acquiescence to the Nazi Party was done to save her life and the lives of her children (his Jewish grandchildren). He was also apolitical, and took the Reichsmusikkammer post to advance copyright protections for composers, attempting as well to preserve performances of works by banned composers such as Mahler and Felix Mendelssohn. Further, Strauss insisted on using a Jewish librettist, Stefan Zweig, for his opera Die schweigsame Frau which ultimately led to his firing from the Reichsmusikkammer and Bayreuth. His opera Friedenstag, which premiered just before the outbreak of World War II, was a thinly veiled criticism of the Nazi Party that attempted to persuade Germans to abandon violence for peace. Thanks to his influence, his daughter-in-law was placed under protected house arrest during the war, but despite extensive efforts he was unable to save dozens of his in-laws from being killed in Nazi concentration camps. In 1948, a year before his death, he was cleared of any wrongdoing by a denazification tribunal in Munich.

10. Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714 - 1787)

With an HPI of 80.81, Christoph Willibald Gluck is the 10th most famous German Composer. His biography has been translated into 68 different languages.

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; German: [ˈkʁɪstɔf ˈvɪlɪbalt ˈɡlʊk]; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a German composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the Holy Roman Empire at the time, he gained prominence at the Habsburg court in Vienna. There he brought about the practical reform of opera's dramaturgical practices for which many intellectuals had been campaigning. With a series of radical new works in the 1760s, among them Orfeo ed Euridice and Alceste, he broke the stranglehold that Metastasian opera seria had enjoyed for much of the century. Gluck introduced more drama by using orchestral recitative and cutting the usually long da capo aria. His later operas have half the length of a typical baroque opera. The strong influence of French opera encouraged Gluck to move to Paris in November 1773. Fusing the traditions of Italian opera and the French (with rich chorus) into a unique synthesis, Gluck wrote eight operas for the Parisian stage. Iphigénie en Tauride (1779) was a great success and is often considered to be his finest work. Though he was extremely popular and widely credited with bringing about a revolution in French opera, Gluck's mastery of the Parisian operatic scene was never absolute. After the poor reception of his Echo et Narcisse (1779), he left Paris in disgust and returned to Vienna to live out the remainder of his life.

People

Pantheon has 180 people classified as German composers born between 1496 and 1974. Of these 180, 9 (5.00%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living German composers include Hans Zimmer, Max Richter, and Helmut Lachenmann. The most famous deceased German composers include Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Sebastian Bach, and George Frideric Handel.

Living German Composers

Go to all RankingsHans Zimmer

1957 - Present

HPI: 76.78

Max Richter

1966 - Present

HPI: 63.05

Helmut Lachenmann

1935 - Present

HPI: 62.60

Ramin Djawadi

1974 - Present

HPI: 59.04

Hauschka

1966 - Present

HPI: 56.34

Klaus Badelt

1967 - Present

HPI: 55.69

Samuel Adler

1928 - Present

HPI: 50.87

Ludger Stühlmeyer

1961 - Present

HPI: 48.52

Masashi Hamauzu

1971 - Present

HPI: 47.51

Deceased German Composers

Go to all RankingsLudwig van Beethoven

1770 - 1827

HPI: 96.89

Johann Sebastian Bach

1685 - 1750

HPI: 92.78

George Frideric Handel

1685 - 1759

HPI: 88.95

Richard Wagner

1813 - 1883

HPI: 88.15

Johannes Brahms

1833 - 1897

HPI: 85.79

Robert Schumann

1810 - 1856

HPI: 84.50

Felix Mendelssohn

1809 - 1847

HPI: 83.51

Jacques Offenbach

1819 - 1880

HPI: 82.37

Richard Strauss

1864 - 1949

HPI: 80.88

Christoph Willibald Gluck

1714 - 1787

HPI: 80.81

Georg Philipp Telemann

1681 - 1767

HPI: 79.39

Carl Maria von Weber

1786 - 1826

HPI: 79.23

Overlapping Lives

Which Composers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Composers since 1700.