The Most Famous

BIOLOGISTS from Austria

This page contains a list of the greatest Austrian Biologists. The pantheon dataset contains 1,097 Biologists, 21 of which were born in Austria. This makes Austria the birth place of the 8th most number of Biologists behind Switzerland, and Russia.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Austrian Biologists of all time. This list of famous Austrian Biologists is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Austrian Biologists.

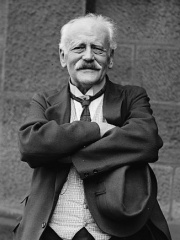

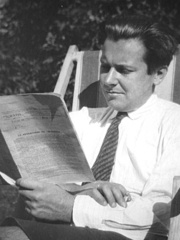

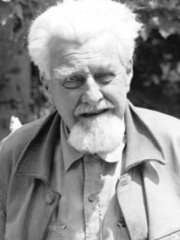

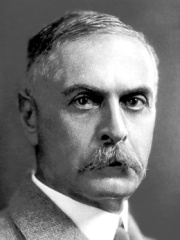

1. Konrad Lorenz (1903 - 1989)

With an HPI of 79.42, Konrad Lorenz is the most famous Austrian Biologist. His biography has been translated into 79 different languages on wikipedia.

Konrad Zacharias Lorenz (Austrian German pronunciation: [ˈkɔnʁaːd tsaxaˈʁiːas ˈloːʁɛnts] ; 7 November 1903 – 27 February 1989) was an Austrian zoologist, ethologist, and ornithologist. He shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Karl von Frisch. He is often regarded as one of the founders of modern ethology, the study of animal behavior. He developed an approach that began with an earlier generation, including his teacher Oskar Heinroth. Lorenz studied instinctive behavior in animals, especially in greylag geese and jackdaws. Working with geese, he investigated the principle of imprinting, the process by which some nidifugous birds (i.e. birds that leave their nest early) bond instinctively with the first moving object that they see within the first hours of hatching. Although Lorenz did not discover the topic, he became widely known for his descriptions of imprinting as an instinctive bond. In 1936, he met Tinbergen, and the two collaborated in developing ethology as a separate sub-discipline of biology. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Lorenz the 65th most cited scholar of the 20th century in the technical psychology journals, introductory psychology textbooks, and survey responses. Lorenz's work was interrupted by the onset of World War II and in 1941 he was recruited into the German Army as a medic. In 1944, he was sent to the Eastern Front where he was captured by the Soviet Red Army and spent four years as a German prisoner of war in Soviet Armenia. After the war, he regretted his membership in the Nazi Party. Lorenz wrote numerous books, some of which, such as King Solomon's Ring, On Aggression, and Man Meets Dog, became popular reading. His last work Here I Am – Where Are You? is a summary of his life's work and focuses on his famous studies of greylag geese.

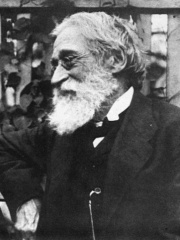

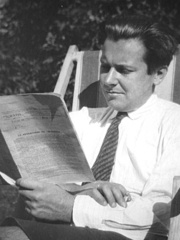

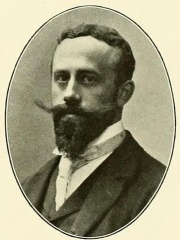

2. Karl Landsteiner (1868 - 1943)

With an HPI of 79.16, Karl Landsteiner is the 2nd most famous Austrian Biologist. His biography has been translated into 86 different languages.

Karl Landsteiner (German: [kaʁl ˈlantˌʃtaɪnɐ]; 14 June 1868 – 26 June 1943) was an Austrian-American biologist, physician, and immunologist. He emigrated with his family to New York in 1923 at the age of 55 for professional opportunities, working for the Rockefeller Institute. He had distinguished the main blood groups in 1901, having developed the modern system of classification of blood groups from his identification of the presence of agglutinins in the blood. In 1937, with Alexander S. Wiener, he identified the Rhesus factor, thus enabling physicians to transfuse blood without endangering the patient's life. With Constantin Levaditi and Erwin Popper, he discovered the polio virus in 1909. He received the Aronson Prize in 1926. In 1930, he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He was posthumously awarded the Lasker Award in 1946, and has been described as the father of transfusion medicine.

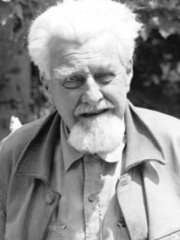

3. Karl von Frisch (1886 - 1982)

With an HPI of 74.03, Karl von Frisch is the 3rd most famous Austrian Biologist. His biography has been translated into 60 different languages.

Karl Ritter von Frisch, (20 November 1886 – 12 June 1982) was a German-Austrian ethologist who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973, along with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Konrad Lorenz. His work centered on investigations of the sensory perceptions of the honey bee and he was one of the first to translate the meaning of the waggle dance. His theory, described in his 1927 book Aus dem Leben der Bienen (translated into English as The Dancing Bees), was disputed by other scientists and greeted with skepticism at the time. Only much later was it shown to be an accurate theoretical analysis.

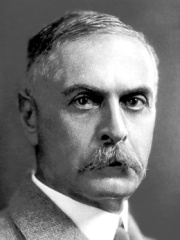

4. Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901 - 1972)

With an HPI of 67.43, Ludwig von Bertalanffy is the 4th most famous Austrian Biologist. His biography has been translated into 29 different languages.

Karl Ludwig von Bertalanffy (19 September 1901 – 12 June 1972) was an Austrian biologist known as one of the founders of general systems theory (GST). This is an interdisciplinary practice that describes systems with interacting components, applicable to biology, cybernetics and other fields. Bertalanffy proposed that the classical laws of thermodynamics might be applied to closed systems, but not necessarily to "open systems" such as living things. His mathematical model of an organism's growth over time, published in 1934, is still in use today. Bertalanffy grew up in Austria and subsequently worked in Vienna, London, Canada, and the United States.

5. Othenio Abel (1875 - 1946)

With an HPI of 65.79, Othenio Abel is the 5th most famous Austrian Biologist. His biography has been translated into 35 different languages.

Othenio Lothar Franz Anton Louis Abel (20 June 1875 – 4 July 1946) was an Austrian paleontologist and evolutionary biologist. Together with Louis Dollo, he was the founder of "paleobiology" and studied the life and environment of fossilized organisms.

6. Joy Adamson (1910 - 1980)

With an HPI of 64.98, Joy Adamson is the 6th most famous Austrian Biologist. Her biography has been translated into 31 different languages.

Friederike Victoria "Joy" Adamson (née Gessner; 20 January 1910 – 3 January 1980) was a naturalist, artist and author. Her book, Born Free, describes her experiences raising a lion cub named Elsa. Born Free was printed in several languages and made into an Academy Award–winning movie of the same name. In 1977, she was awarded the Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art.

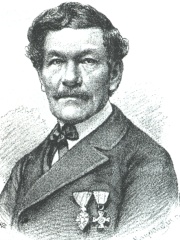

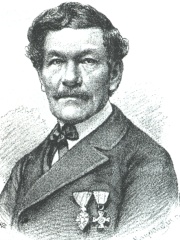

7. Leopold Fitzinger (1802 - 1884)

With an HPI of 64.45, Leopold Fitzinger is the 7th most famous Austrian Biologist. His biography has been translated into 31 different languages.

Leopold Joseph Franz Johann Fitzinger (13 April 1802 – 20 September 1884) was an Austrian zoologist. Fitzinger was born in Vienna and studied botany at the University of Vienna under Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin. He worked at the Vienna Naturhistorisches Museum between 1817, when he joined as a volunteer assistant, and 1821, when he left to become secretary to the provincial legislature of Lower Austria; after a hiatus, he was appointed assistant curator in 1844 and remained at the Naturhistorisches Museum until 1861. Later, he became director of the zoos of Munich and Budapest. In 1826, he published Neue Classification der Reptilien, based partly on the work of his friends Friedrich Wilhelm Hemprich and Heinrich Boie. In 1843, he published Systema Reptilium, covering geckos, chameleons and iguanas. Fitzinger is commemorated in the scientific names of five reptiles: Algyroides fitzingeri, Leptotyphlops fitzingeri, Liolaemus fitzingerii, Micrurus tener fitzingeri, and Oxyrhopus fitzingeri. Works

8. Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti (1735 - 1805)

With an HPI of 64.15, Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti is the 8th most famous Austrian Biologist. His biography has been translated into 27 different languages.

Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti (4 December 1735, Vienna – 17 February 1805, Vienna) was an Austrian naturalist and zoologist of Italian origin. Laurenti is considered the auctor of the class Reptilia (reptiles) through his authorship of Specimen Medicum, Exhibens Synopsin Reptilium Emendatam cum Experimentis circa Venena (1768) on the poisonous function of reptiles and amphibians. This was an important book in herpetology, defining thirty genera of reptiles; Carl Linnaeus's 10th edition of Systema Naturae in 1758 defined only ten genera. Specimen Medicum contains a description of the blind salamander (amphibian): Proteus anguinus, purportedly collected from cave waters in Slovenia (or possibly western Croatia); this description represented one of the first published accounts of a cave animal in the western world, although Proteus anguinus was not recognized as a cave animal at the time. In the past, Laurenti's authorship of his work has been doubted several times and attributed to the Hungarian scientist Jacob Joseph Winterl, but without substantive evidence.

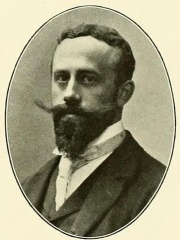

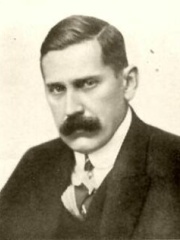

9. Erich von Tschermak (1871 - 1962)

With an HPI of 63.31, Erich von Tschermak is the 9th most famous Austrian Biologist. His biography has been translated into 26 different languages.

Erich Tschermak, Edler von Seysenegg (15 November 1871 – 11 October 1962) was an Austrian agronomist who developed several new disease-resistant crops, including wheat-rye and oat hybrids. He was a son of the Moravia-born mineralogist Gustav Tschermak von Seysenegg. His maternal grandfather was the botanist, Eduard Fenzl, who taught Gregor Mendel botany during his student days in Vienna. He received his doctorate from the University of Halle, Germany, in 1896. Tschermak accepted a teaching position at the University of Agricultural Sciences Vienna in 1901, and became professor there five years later, in 1900. Von Tschermak is one of four men—see also Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns and William Jasper Spillman—who independently rediscovered Gregor Mendel's work on genetics. Von Tschermak published his findings in June, 1900. His works in genetics were largely influenced by his brother Armin von Tschermak-Seysenegg.

10. Clemens von Pirquet (1874 - 1929)

With an HPI of 61.08, Clemens von Pirquet is the 10th most famous Austrian Biologist. His biography has been translated into 22 different languages.

Clemens Peter Freiherr von Pirquet (12 May 1874 – 28 February 1929) was an Austrian scientist and pediatrician best known for his contributions to the fields of bacteriology and immunology.

People

Pantheon has 21 people classified as Austrian biologists born between 1727 and 1967. Of these 21, none of them are still alive today. The most famous deceased Austrian biologists include Konrad Lorenz, Karl Landsteiner, and Karl von Frisch.

Deceased Austrian Biologists

Go to all RankingsKonrad Lorenz

1903 - 1989

HPI: 79.42

Karl Landsteiner

1868 - 1943

HPI: 79.16

Karl von Frisch

1886 - 1982

HPI: 74.03

Ludwig von Bertalanffy

1901 - 1972

HPI: 67.43

Othenio Abel

1875 - 1946

HPI: 65.79

Joy Adamson

1910 - 1980

HPI: 64.98

Leopold Fitzinger

1802 - 1884

HPI: 64.45

Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti

1735 - 1805

HPI: 64.15

Erich von Tschermak

1871 - 1962

HPI: 63.31

Clemens von Pirquet

1874 - 1929

HPI: 61.08

Otto Stapf

1857 - 1933

HPI: 58.90

Franz Steindachner

1834 - 1919

HPI: 58.80

Overlapping Lives

Which Biologists were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 20 most globally memorable Biologists since 1700.