The Most Famous

RELIGIOUS FIGURES from Turkey

This page contains a list of the greatest Turkish Religious Figures. The pantheon dataset contains 3,187 Religious Figures, 17 of which were born in Turkey. This makes Turkey the birth place of the 33rd most number of Religious Figures behind Croatia, and Brazil.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Turkish Religious Figures of all time. This list of famous Turkish Religious Figures is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography’s online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Turkish Religious Figures.

1. Ulfilas (311 - 383)

With an HPI of 74.84, Ulfilas is the most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 54 different languages on wikipedia.

Ulfilas (Greek: Οὐλφίλας; c. 311 – 383), known also as Wulfila(s) or Urphilas, was a 4th-century Gothic preacher of Cappadocian Greek descent. He was the apostle to the Gothic people. Ulfila served as a bishop and missionary, participated in the Arian controversy, and is credited with converting the Goths to Christianity as well as overseeing translation of the Bible into the Gothic language. For the purpose of the translation he developed the Gothic alphabet, largely based on the Greek alphabet, as well as Latin and Runic characters. Although the translation of the text into Gothic has traditionally been ascribed to Ulfila, analysis of the text of the Gothic Bible indicates the involvement of a team of translators, possibly under his supervision.

2. Clement of Ohrid (840 - 916)

With an HPI of 73.33, Clement of Ohrid is the 2nd most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 38 different languages.

Saint Clement (or Kliment) of Ohrid (Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbian: Климент Охридски, Kliment Ohridski; Ancient Greek: Κλήμης τῆς Ἀχρίδας, Klḗmēs tē̂s Akhrídas; Slovak: Kliment Ochridský; c. 830 – 916) was one of the first medieval Bulgarian saints, scholar, writer, and apostle to the Slavs. He was one of the most prominent disciples of Cyril and Methodius and is often associated with the creation of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts, especially their popularisation among Christianised Slavs. He was the founder of the Ohrid Literary School and is regarded as a patron of education and language by some Slavic people. He is considered to be the first bishop of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, one of the Seven Apostles of Bulgarian Orthodox Church since the 10th century, and one of the premier saints of modern Bulgaria. The mission of Clement was the crucial factor which transformed the Slavs in then Kutmichevitsa (present-day Macedonia) into Bulgarians. Clement is also the patron saint of North Macedonia, the city of Ohrid and the Macedonian Orthodox Church.

3. Dionysius Exiguus (475 - 544)

With an HPI of 73.30, Dionysius Exiguus is the 3rd most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 41 different languages.

Dionysius Exiguus (Latin for "Dionysius the Humble"; Greek: Διονύσιος; c. 470 – c. 544) was a 6th-century Eastern Roman monk born in Scythia Minor. He was a member of a community of Scythian monks concentrated in Tomis (present-day Constanța, Romania), the major city of Scythia Minor. Dionysius is best known as the inventor of Anno Domini (AD) dating, which is used to number the years of both the Gregorian calendar and the (Christianised) Julian calendar. Almost all churches adopted his computus for the dates of Easter. From around the year 500 until his death, Dionysius lived in Rome. He translated 401 Church canons from Greek into Latin, including the Apostolic Canons and the decrees of the First Council of Nicaea, First Council of Constantinople, Council of Chalcedon, and Council of Sardica, and a collection of the decretals of the popes from Siricius to Anastasius II. These Collectiones canonum Dionysianae had great authority in the West, and they continue to guide church administrations. Dionysius also wrote a treatise on elementary mathematics. The author of a continuation of Dionysius's Computus, writing in 616, described Dionysius as a "most learned abbot of the city of Rome", and the Venerable Bede accorded him the honorific abbas (which could be applied to any monk, especially a senior and respected monk, and does not necessarily imply that Dionysius ever headed a monastery; indeed, Dionysius's friend Cassiodorus stated in Institutiones that he was still an ordinary monk late in life).

4. Pope Vitalian (600 - 672)

With an HPI of 73.11, Pope Vitalian is the 4th most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 68 different languages.

Pope Vitalian (Latin: Vitalianus; died 27 January 672) was the bishop of Rome from 30 July 657 to his death in 672. His pontificate was marked by the dispute between the papacy and the imperial government in Constantinople over Monothelitism, which Rome condemned. Vitalian tried to resolve the dispute and had a conciliatory relationship with Emperor Constans II, who visited him in Rome and gave him gifts. Vitalian's pontificate also saw the secession of the Archbishopric of Ravenna from the papal authority.

5. Pope Sabinian (530 - 606)

With an HPI of 72.93, Pope Sabinian is the 5th most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 67 different languages.

Pope Sabinian (Latin: Sabinianus) was the bishop of Rome from 13 September 604 to his death on 22 February 606. His pontificate occurred during the Eastern Roman domination of the papacy. He was the fourth former apocrisiarius to Constantinople to be elected pope.

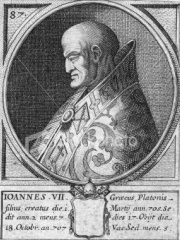

6. Pope John VII (650 - 707)

With an HPI of 71.11, Pope John VII is the 6th most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 71 different languages.

Pope John VII (Latin: Ioannes VII; c. 650 – 18 October 707) was the bishop of Rome from 1 March 705 to his death. He was an ethnic Greek, one of the Byzantine popes, but had better relations with the Lombards, who ruled much of Italy, than with Emperor Justinian II, who ruled the rest.

7. Philemon (100 - 68)

With an HPI of 68.73, Philemon is the 7th most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 26 different languages.

Philemon (; Ancient Greek: Φιλήμων, Philḗmōn) was an early Christian in Asia Minor who was the recipient of a private letter from Paul of Tarsus which forms part of the Christian New Testament. This letter is known as Epistle to Philemon, although it is addressed "to Philemon, our dear friend and fellow worker, also to Apphia our sister and Archippus our fellow soldier, and to the church that meets in your home". Paul asks Philemon to "take back" Onesimus, who may previously have been his slave. Philemon is known as a saint by several Christian churches along with Apphia (or Appia), seen as his wife. Philemon was a wealthy Christian and a minister (possibly a bishop). The Menaia of 22 November speak of Philemon as a holy apostle who, in company with Apphia, Archippus, and Onesimus, had been martyred at Colossae during the first general persecution in the reign of Nero. In the list of the Seventy Apostles, attributed to Dorotheus of Tyre, Philemon is described as bishop of Gaza.

8. Theophilus of Antioch (140 - 183)

With an HPI of 68.08, Theophilus of Antioch is the 8th most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 35 different languages.

There is also a Theophilus of Alexandria (c. 412) Theophilus of Antioch (Greek: Θεόφιλος ὁ Ἀντιοχεύς) was Patriarch of Antioch from 169 until 183. He succeeded Eros of Antioch c. 169, and was succeeded by Maximus I c. 183, according to Henry Fynes Clinton, but these dates are only approximations. His death probably occurred between 183 and 185. His writings (the only remaining being his apology to Autolycus) indicate that he was born a pagan, not far from the Tigris and Euphrates, and was led to embrace Christianity by studying the Holy Scriptures, especially the prophetical books. He makes no reference to his office in his existing writings, nor is any other fact in his life recorded. Eusebius, however, speaks of the zeal which he and the other chief shepherds displayed in driving away the heretics who were attacking Christ's flock, with special mention of his work against Marcion. He made contributions to the departments of Christian literature, polemics, exegetics, and apologetics. William Sanday describes him as "one of the precursors of that group of writers who, from Irenaeus to Cyprian, not only break the obscurity which rests on the earliest history of the Church, but alike in the East and in the West carry it to the front in literary eminence, and distance all their heathen contemporaries".

9. Expeditus (300 - 303)

With an HPI of 67.60, Expeditus is the 9th most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 21 different languages.

Expeditus (died 303), also known as Expedite, was said to have been a Roman centurion in Armenia who was martyred around April 303 in what is now Turkey, for converting to Christianity. Considered the patron saint of urgent causes, he is also known as the saint of time; he was commemorated by the Catholic Church on 19 April.

10. Papias of Hierapolis (70 - 100)

With an HPI of 67.30, Papias of Hierapolis is the 10th most famous Turkish Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 39 different languages.

Papias (Greek: Παπίας) was a Greek Apostolic Father, Bishop of Hierapolis (modern Pamukkale, Turkey), and author who lived c. 60 – c. 130 AD He wrote the Exposition of the Sayings of the Lord (Greek: Λογίων Κυριακῶν Ἐξήγησις) in five books. This work, which is lost apart from brief excerpts in the works of Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 180) and Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 320), is an important early source on Christian oral tradition and especially on the origins of the canonical Gospels.

People

Pantheon has 17 people classified as Turkish religious figures born between 20 and 900. Of these 17, none of them are still alive today. The most famous deceased Turkish religious figures include Ulfilas, Clement of Ohrid, and Dionysius Exiguus.

Deceased Turkish Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsUlfilas

311 - 383

HPI: 74.84

Clement of Ohrid

840 - 916

HPI: 73.33

Dionysius Exiguus

475 - 544

HPI: 73.30

Pope Vitalian

600 - 672

HPI: 73.11

Pope Sabinian

530 - 606

HPI: 72.93

Pope John VII

650 - 707

HPI: 71.11

Philemon

100 - 68

HPI: 68.73

Theophilus of Antioch

140 - 183

HPI: 68.08

Expeditus

300 - 303

HPI: 67.60

Papias of Hierapolis

70 - 100

HPI: 67.30

Flavian of Constantinople

380 - 449

HPI: 66.81

Melito of Sardis

140 - 180

HPI: 65.34