The Most Famous

COMPOSERS from Russia

This page contains a list of the greatest Russian Composers. The pantheon dataset contains 1,451 Composers, 68 of which were born in Russia. This makes Russia the birth place of the 6th most number of Composers behind United States, and United Kingdom.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Russian Composers of all time. This list of famous Russian Composers is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Russian Composers.

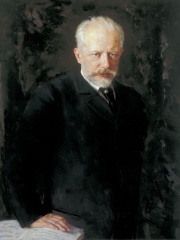

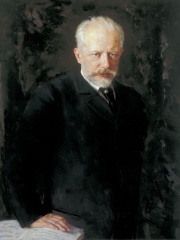

1. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 - 1893)

With an HPI of 89.39, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky is the most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 155 different languages on wikipedia.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ( chy-KOF-skee; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally. Tchaikovsky wrote some of the most popular concert and theatrical music in the classical repertoire, including the ballets Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, the 1812 Overture, his First Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, the Romeo and Juliet Overture-Fantasy, several symphonies, and the opera Eugene Onegin. Although musically precocious, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil servant as there was little opportunity for a musical career in Russia at the time and no public music education system. When an opportunity for such an education arose, he entered the nascent Saint Petersburg Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1865. The formal Western-oriented teaching Tchaikovsky received there set him apart from composers of the contemporary nationalist movement embodied by the Russian composers of The Five, with whom his professional relationship was mixed. Tchaikovsky's training set him on a path to reconcile what he had learned with the native musical practices to which he had been exposed from childhood. From that reconciliation, he forged a personal but unmistakably Russian style. The principles that governed melody, harmony, and other fundamentals of Russian music diverged from those that governed Western European music. There seemed to be little potential for using Russian music in large-scale Western composition or for forming a composite style, and this caused personal antipathies that dented Tchaikovsky's self-confidence. Russian culture exhibited a split personality, with its native and adopted elements having drifted apart increasingly since the time of Peter the Great. That resulted in uncertainty among the intelligentsia about the country's national identity, an ambiguity mirrored in Tchaikovsky's career. Despite his many popular successes, Tchaikovsky's life was punctuated by personal crises and depression. Contributory factors included his early separation from his mother for boarding school followed by her early death, the death of his close friend and colleague Nikolai Rubinstein, his failed marriage to Antonina Miliukova, and the collapse of his 13-year association with the wealthy patroness Nadezhda von Meck. Tchaikovsky's homosexuality, which he kept private, has traditionally also been considered a major factor, though some scholars have downplayed its importance. His dedication of his Sixth symphony to his nephew Vladimir Davydov and the feelings he expressed about Davydov in letters to others have been cited as evidence for romantic love between the two. Tchaikovsky's sudden death at the age of 53 is generally ascribed to cholera, but there is an ongoing debate as to whether cholera was indeed the cause and whether the death was intentional. While his music has remained popular among audiences, critical opinions were initially mixed. Some Russians did not feel it sufficiently represented native musical values and expressed suspicion that Europeans accepted the music for its Western elements. In an apparent reinforcement of that claim, some Europeans lauded Tchaikovsky for offering music more substantive than exoticism, and said he transcended the stereotypes of Russian classical music. Others dismissed Tchaikovsky's music as deficient because it did not stringently follow Western principles.

2. Igor Stravinsky (1882 - 1971)

With an HPI of 87.34, Igor Stravinsky is the 2nd most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 133 different languages.

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (17 June [O.S. 5 June] 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer and conductor with French citizenship (from 1934) and American citizenship (from 1945). He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century and a pivotal figure in modernist music. Born to a musical family in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Stravinsky grew up taking piano and music theory lessons. While studying law at the University of Saint Petersburg, he met Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and studied music under him until the latter's death in 1908. Stravinsky met the impresario Sergei Diaghilev soon after, who commissioned the composer to write three ballets for the Ballets Russes's Paris seasons: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911), and The Rite of Spring (1913), the last of which caused a near-riot at the premiere due to its avant-garde nature and later changed the way composers understood rhythmic structure. Stravinsky's compositional career is often divided into three main periods: his Russian period (1913–1920), his neoclassical period (1920–1951), and his serial period (1954–1968). During his Russian period, Stravinsky was heavily influenced by Russian styles and folklore. Works such as Renard (1916) and Les noces (1923) drew upon Russian folk poetry, while compositions like L'Histoire du soldat (1918) integrated these folk elements with popular musical forms, including the tango, waltz, ragtime, and chorale. His neoclassical period exhibited themes and techniques from the classical period, like the use of the sonata form in his Octet (1923) and use of Greek mythological themes in works including Apollon musagète (1927), Oedipus rex (1927), and Persephone (1935). In his serial period, Stravinsky turned towards compositional techniques from the Second Viennese School like Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique. In Memoriam Dylan Thomas (1954) was the first of his compositions to be fully based on the technique, and Canticum Sacrum (1956) was his first to be based on a tone row. Stravinsky's last major work was the Requiem Canticles (1966), which was performed at his funeral. While many supporters were confused by Stravinsky's constant stylistic changes, later writers recognized his versatile language as important in the development of modernist music. Stravinsky's revolutionary ideas influenced composers as diverse as Aaron Copland, Philip Glass, Béla Bartók, and Pierre Boulez, who were all challenged to innovate music in areas beyond tonality, especially rhythm and musical form. In 1998, Time magazine listed Stravinsky as one of the 100 most influential people of the century. Stravinsky died of pulmonary edema on 6 April 1971 in New York City, having left six memoirs written with his friend and assistant Robert Craft, as well as an earlier autobiography and a series of lectures.

3. Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 - 1975)

With an HPI of 82.02, Dmitri Shostakovich is the 3rd most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 82 different languages.

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (25 September [O.S. 12 September] 1906 – 9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer. Shostakovich achieved early fame in the Soviet Union, but had a complex relationship with its government. His 1934 opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was initially a success but later condemned by the Soviet government, putting his career at risk. In 1948, his work was denounced under the Zhdanov Doctrine, with professional consequences lasting several years. Even after his censure was rescinded in 1956, performances of his music were occasionally subject to state interventions, as with his Thirteenth Symphony (1962). Nevertheless, Shostakovich was a member of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR (1947) and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union (from 1962 until his death), as well as chairman of the RSFSR Union of Composers (1960–1968). Over the course of his career, he earned several important awards, including the Order of Lenin, from the Soviet government. Shostakovich combined various musical techniques in his works. His music is characterized by sharp contrasts, elements of the grotesque, and ambivalent tonality; he was also heavily influenced by neoclassicism and by the music of Gustav Mahler. His orchestral works include 15 symphonies and six concerti (two each for piano, violin, and cello). His chamber works include 15 string quartets, a piano quintet, and two piano trios. His solo piano works include two sonatas, an early set of 24 preludes, and a later set of 24 preludes and fugues. Stage works include three completed operas and three ballets. Shostakovich also wrote several song cycles and a substantial quantity of music for theatre and film. Shostakovich's reputation has continued to grow after his death. Scholarly interest has increased significantly since the late 20th century, including considerable debate about the relationship between his music and his attitudes toward the Soviet government.

4. Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 - 1943)

With an HPI of 81.11, Sergei Rachmaninoff is the 4th most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 75 different languages.

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff (1 April [O.S. 20 March] 1873 – 28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of the last great representatives of Romanticism in Russian classical music. Early influences of Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and other Russian composers gave way to a thoroughly personal idiom notable for its song-like melodicism, expressiveness, dense contrapuntal textures, and rich orchestral colours. The piano is featured prominently in Rachmaninoff's compositional output and he used his skills as a performer to fully explore the expressive and technical possibilities of the instrument. Born into a musical family, Rachmaninoff began learning the piano at the age of four. He studied piano and composition at the Moscow Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1892, having already written several compositions. In 1897, following the disastrous premiere of his Symphony No. 1, Rachmaninoff entered a four-year depression and composed little, until supportive therapy allowed him to complete his well-received Piano Concerto No. 2 in 1901. Rachmaninoff went on to become conductor of the Bolshoi Theatre from 1904 to 1906, and relocated to Dresden, Germany, in 1906. He later embarked upon his first tour of the United States as a concert pianist in 1909. After the Russian Revolution, Rachmaninoff and his family left Russia permanently, settling in New York in 1918. Following this, he spent most of his time touring as a pianist in the US and Europe, from 1932 onwards spending his summers at his villa in Switzerland. During this time, Rachmaninoff's primary occupation was performing, and his compositional output decreased significantly, completing just six works after leaving Russia. By 1942, his declining health led him to move to Beverly Hills, California, where he died from melanoma in 1943.

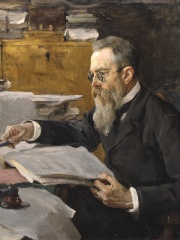

5. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844 - 1908)

With an HPI of 80.32, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov is the 5th most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 81 different languages.

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (18 March 1844 – 21 June 1908) was a Russian composer, a member of the group of composers known as The Five. His best-known orchestral compositions—Capriccio Espagnol, the Russian Easter Festival Overture, and the symphonic suite Scheherazade—are staples of the classical music repertoire, along with suites and excerpts from some of his fifteen operas. Scheherazade is an example of his frequent use of fairy-tale and folk subjects. Rimsky-Korsakov believed in developing a nationalistic style of classical music, employing Russian folk song and lore along with exotic harmonic, melodic and rhythmic elements in a practice known as musical orientalism, and eschewing traditional Western compositional methods. Rimsky-Korsakov appreciated Western musical techniques after he became a professor of musical composition, harmony, and orchestration at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1871. He undertook a rigorous three-year program of self-education and became a master of Western methods, incorporating them alongside the influences of Mikhail Glinka and fellow members of The Five. Rimsky-Korsakov's techniques of composition and orchestration were further enriched by his exposure to the works of Richard Wagner. For much of his life, Rimsky-Korsakov combined his composition and teaching with a career in the Russian armed forces—first as an officer in the Imperial Russian Navy, then as the civilian Inspector of Naval Bands. He wrote that he developed a passion for the ocean in childhood from reading books and hearing of his older brother's exploits in the navy. This love of the sea may have influenced him to write two of his best-known orchestral works, the musical tableau Sadko (not to be confused with his later opera of the same name) and Scheherazade. As Inspector of Naval Bands, Rimsky-Korsakov expanded his knowledge of woodwind and brass playing, which enhanced his abilities in orchestration. He passed this knowledge to his students, and also posthumously through a textbook on orchestration that was completed by his son-in-law Maximilian Steinberg. Rimsky-Korsakov left a considerable body of original Russian nationalist compositions. He prepared works by The Five for performance, which brought them into the active classical repertoire (although there is controversy over his editing of the works of Modest Mussorgsky), and shaped a generation of younger composers and musicians during his decades as an educator. Rimsky-Korsakov is therefore considered "the main architect" of what the classical-music public considers the "Russian style". His influence on younger composers was especially important, as he served as a transitional figure between the autodidactism exemplified by Glinka and The Five, and professionally trained composers, who became the norm in Russia by the closing years of the 19th century. While Rimsky-Korsakov's style was based on those of Glinka, Balakirev, Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt and, for a brief period, Wagner, he "transmitted this style directly to two generations of Russian composers" and influenced non-Russian composers including Maurice Ravel, Claude Debussy, Paul Dukas, and Ottorino Respighi.

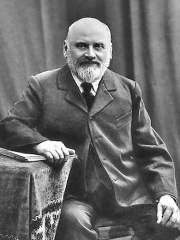

6. Modest Mussorgsky (1839 - 1881)

With an HPI of 79.87, Modest Mussorgsky is the 6th most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 78 different languages.

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (; Russian: Модест Петрович Мусоргский, romanized: Modest Petrovich Musorgsky; IPA: [mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj] ; 21 March [O.S. 9 March] 1839 – 28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1881) was a Russian composer, one of the group known as "The Five." He was an innovator of Russian music in the Romantic period and strove to achieve a uniquely Russian musical identity, often in deliberate defiance of the established conventions of Western music. Many of Mussorgsky's works were inspired by Russian history, Russian folklore, and other national themes. Such works include the opera Boris Godunov, the orchestral tone poem Night on Bald Mountain and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition. For many years, Mussorgsky's works were mainly known in versions revised or completed by other composers. Many of his most important compositions have posthumously come into their own in their original forms, and some of the original scores are now also available.

7. Alexander Borodin (1833 - 1887)

With an HPI of 77.17, Alexander Borodin is the 7th most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 77 different languages.

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin (12 November 1833 – 27 February 1887) was a Russian Romantic composer and chemist of Georgian–Russian parentage. He was one of the prominent 19th-century composers known as "The Five", a group dedicated to producing a "uniquely Russian" kind of classical music. Borodin is known best for his symphonies, his two string quartets, the symphonic poem In the Steppes of Central Asia and his opera Prince Igor. A doctor and chemist by profession and training, Borodin made important early contributions to organic chemistry. Although he is presently known better as a composer, he regarded medicine and science as his primary occupations, only practising music and composition in his spare time or when he was ill. As a chemist, Borodin is known best for his work concerning organic synthesis, including being among the first chemists to demonstrate nucleophilic substitution, as well as being the co-discoverer of the aldol reaction. Borodin was a promoter of education in Russia and founded the School of Medicine for Women in Saint Petersburg, where he taught until 1885. In the 1880s pressures of work and ill health left him little time for composition. He died suddenly in 1887 while at a ball.

8. Alexander Scriabin (1871 - 1915)

With an HPI of 77.03, Alexander Scriabin is the 8th most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 65 different languages.

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (6 January 1872 [O.S. 25 December 1871] – 27 April [O.S. 14 April] 1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and composed in a relatively tonal, late-Romantic idiom. Later, and independently of his influential contemporary Arnold Schoenberg, Scriabin developed a much more dissonant musical language that had transcended usual tonality but was not atonal, which accorded with his personal brand of metaphysics. Scriabin found significant appeal in the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk as well as synesthesia, and associated colours with the various harmonic tones of his scale, while his colour-coded circle of fifths was also inspired by theosophy. He is often considered the main Russian symbolist composer and a major representative of the Russian Silver Age. Scriabin was an innovator and one of the most controversial composer-pianists of the early 20th century. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia said of him, "no composer has had more scorn heaped on him or greater love bestowed." Leo Tolstoy described Scriabin's music as "a sincere expression of genius." Scriabin's oeuvre exerted a salient influence on the music world over time, and inspired many composers, such as Nikolai Roslavets and Karol Szymanowski. But Scriabin's importance in the Russian (subsequently Soviet) musical scene, and internationally, drastically declined after his death. According to his biographer Faubion Bowers, "No one was more famous during their lifetime, and few were more quickly ignored after death." Nevertheless, his musical aesthetics have been reevaluated since the 1970s, and his ten published sonatas for piano and other works have been increasingly championed, garnering significant acclaim in recent years.

9. Mikhail Glinka (1804 - 1857)

With an HPI of 74.38, Mikhail Glinka is the 9th most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 64 different languages.

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (Russian: Михаил Иванович Глинка, romanized: Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka, IPA: [mʲɪxɐˈil ɨˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə] ; 1 June [O.S. 20 May] 1804 – 15 February [O.S. 3 February] 1857) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognition within his own country and is often regarded as the fountainhead of Russian classical music. His compositions were an important influence on other Russian composers, notably the members of The Five, who produced a distinctive Russian style of music.

10. Mily Balakirev (1837 - 1910)

With an HPI of 74.24, Mily Balakirev is the 10th most famous Russian Composer. His biography has been translated into 62 different languages.

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev (UK: bə-LA(H)K-i-rev, US: BAH-lah-KEER-ef; Russian: Милий Алексеевич Балакирев, pronounced [ˈmʲilʲɪj ɐlʲɪkˈsʲe(j)ɪvʲɪdʑ bɐˈlakʲɪrʲɪf] ; 2 January 1837 [O.S. 21 December 1836] – 29 May [O.S. 16 May] 1910) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor known today primarily for his work promoting musical nationalism and his encouragement of more famous Russian composers, notably Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. He began his career as a pivotal figure, extending the fusion of traditional folk music and experimental classical music practices begun by composer Mikhail Glinka. In the process, Balakirev developed musical patterns that could express overt nationalistic feeling. After a nervous breakdown and consequent sabbatical, he returned to classical music but did not wield the same level of influence as before. In conjunction with critic and fellow nationalist Vladimir Stasov, in the late 1850s and early 1860s, Balakirev brought together the composers now known as The Five (a.k.a., The Mighty Handful) – the others were Alexander Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. For several years, Balakirev was the only professional musician of the group; the others were amateurs limited in musical education. He imparted to them his musical beliefs, which continued to underlie their thinking long after he left the group in 1871, and encouraged their compositional efforts. While his methods could be dictatorial, the results of his influence were several works which established these composers' reputations individually and as a group. He performed a similar function for Tchaikovsky at two points in the latter's career – in 1868–69 with the fantasy-overture Romeo and Juliet, and in 1882–85 with the Manfred Symphony. As a composer, Balakirev finished major works many years after he had started them; he began his First Symphony in 1864 but completed it in 1897. The exception to this was his oriental fantasy Islamey for solo piano, which he composed quickly and remains popular among virtuosos. Often, the musical ideas normally associated with Rimsky-Korsakov or Borodin originated in Balakirev's compositions, which Balakirev played at informal gatherings of The Five. However, his slow pace in completing works for the public deprived him of credit for his inventiveness, and pieces that would have enjoyed success had they been completed in the 1860s and 1870s made a much smaller impact. Balakirev began work on a second symphony, Symphony No. 2 in D minor in 1900, but did not complete the work until 1908.

People

Pantheon has 68 people classified as Russian composers born between 1752 and 1973. Of these 68, 10 (14.71%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Russian composers include Aleksandra Pakhmutova, Airat Ichmouratov, and Valeri Brainin. The most famous deceased Russian composers include Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Igor Stravinsky, and Dmitri Shostakovich. As of April 2024, 1 new Russian composers have been added to Pantheon including Igor Nikolayev.

Living Russian Composers

Go to all RankingsAleksandra Pakhmutova

1929 - Present

HPI: 62.54

Airat Ichmouratov

1973 - Present

HPI: 60.05

Valeri Brainin

1948 - Present

HPI: 57.20

Aulis Sallinen

1935 - Present

HPI: 56.87

Shlomo Mintz

1957 - Present

HPI: 55.60

Vladimir Martynov

1946 - Present

HPI: 54.17

Igor Nikolayev

1960 - Present

HPI: 51.09

Vladimir Jurowski

1972 - Present

HPI: 50.42

Lera Auerbach

1973 - Present

HPI: 48.41

Igor Khoroshev

1965 - Present

HPI: 42.32

Deceased Russian Composers

Go to all RankingsPyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

1840 - 1893

HPI: 89.39

Igor Stravinsky

1882 - 1971

HPI: 87.34

Dmitri Shostakovich

1906 - 1975

HPI: 82.02

Sergei Rachmaninoff

1873 - 1943

HPI: 81.11

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

1844 - 1908

HPI: 80.32

Modest Mussorgsky

1839 - 1881

HPI: 79.87

Alexander Borodin

1833 - 1887

HPI: 77.17

Alexander Scriabin

1871 - 1915

HPI: 77.03

Mikhail Glinka

1804 - 1857

HPI: 74.38

Mily Balakirev

1837 - 1910

HPI: 74.24

Sofia Gubaidulina

1931 - 2025

HPI: 72.54

Dmitry Kabalevsky

1904 - 1986

HPI: 70.07

Newly Added Russian Composers (2025)

Go to all RankingsOverlapping Lives

Which Composers were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Composers since 1700.