The Most Famous

SCULPTORS from Italy

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Italian Sculptors of all time. This list of famous Italian Sculptors is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Italian Sculptors.

1. Benvenuto Cellini (1500 - 1571)

With an HPI of 76.99, Benvenuto Cellini is the most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 53 different languages on wikipedia.

Benvenuto Cellini (, Italian: [beɱveˈnuːto tʃelˈliːni]; 3 November 1500 – 13 February 1571) was an Italian goldsmith, sculptor, and author. His best-known extant works include the Cellini Salt Cellar, the sculpture of Perseus with the Head of Medusa, and his autobiography, which has been described as "one of the most important documents of the 16th century".

2. Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378 - 1455)

With an HPI of 76.50, Lorenzo Ghiberti is the 2nd most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 48 different languages.

Lorenzo Ghiberti (UK: , US: , Italian: [loˈrɛntso ɡiˈbɛrti]; né di Bartolo; 1378 – 1 December 1455) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor from Florence, a key figure in the Early Renaissance, best known as the creator of two sets of bronze doors of the Florence Baptistery, the later one called by Michelangelo the Gates of Paradise. Trained as a goldsmith and sculptor, he established an important workshop for sculpture in metal. His book of Commentarii contains important writing on art, as well as what may be the earliest surviving autobiography by any artist. Ghiberti's career was dominated by his two successive commissions for pairs of bronze doors to the Florence Baptistery (Battistero di San Giovanni). They are recognized as a major masterpiece of the Early Renaissance, and were famous and influential from their unveiling.

3. Antonio Canova (1757 - 1822)

With an HPI of 76.37, Antonio Canova is the 3rd most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 56 different languages.

Antonio Canova (Italian pronunciation: [anˈtɔːnjo kaˈnɔːva]; 1 November 1757 – 13 October 1822) was an Italian Neoclassical sculptor, famous for his marble sculptures. Often regarded as the greatest of the Neoclassical artists, his sculpture was inspired by the Baroque and the classical revival, and has been characterised as having avoided the melodramatics of the former, and the cold artificiality of the latter.

4. Jacopo Sansovino (1486 - 1570)

With an HPI of 71.91, Jacopo Sansovino is the 4th most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 43 different languages.

Jacopo d'Antonio Sansovino (2 July 1486 – 27 November 1570) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor and architect, best known for his works around the Piazza San Marco in Venice. These are crucial works in the history of Venetian Renaissance architecture. Andrea Palladio, in the Preface to his Quattro Libri was of the opinion that Sansovino's Biblioteca Marciana was the best building erected since Antiquity. Giorgio Vasari uniquely printed his Vita of Sansovino separately.

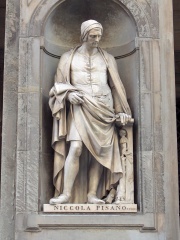

5. Nicola Pisano (1225 - 1284)

With an HPI of 71.85, Nicola Pisano is the 5th most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 34 different languages.

Nicola Pisano (also called Niccolò Pisano, Nicola de Apulia or Nicola Pisanus; c. 1220/1225 – c. 1284) was an Italian sculptor whose work is noted for its classical Roman sculptural style. Pisano is sometimes considered to be the founder of modern sculpture.

6. Luca della Robbia (1399 - 1482)

With an HPI of 71.48, Luca della Robbia is the 6th most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 38 different languages.

Luca della Robbia (, also US: , Italian: [ˈluːka della ˈrobbja, - ˈrɔb-]; 1399/1400–1482) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor from Florence. Della Robbia is noted for his colorful, tin-glazed terracotta statuary, a technique that he invented and passed on to his nephew Andrea della Robbia and great-nephews Giovanni della Robbia and Girolamo della Robbia. Although a leading sculptor in stone, after developing his technique in the early 1440s he worked primarily in terracotta. His large workshop produced both less expensive works cast from molds in multiple versions, and more expensive one-off individually modeled pieces. The vibrant, polychrome glazes made his creations both more expressive and more durable. His work is noted for its charm rather than the drama of the work of some of his contemporaries. Two of his famous works are The Nativity (c. 1460) and Madonna and Child (c. 1475). In stone, his most famous work is also his first major commission, the choir gallery, Cantoria in the Florence Cathedral (1431–1438). Della Robbia was praised by his compatriot Leon Battista Alberti for genius comparable to that of the sculptors Donatello and Lorenzo Ghiberti, the architect Filippo Brunelleschi, and the painter Masaccio. By ranking him with contemporary artists of this stature, Alberti noted the interest and strength of Luca's work in marble and bronze, as well as in the terra-cottas always associated with his name.

7. Andrea Pisano (1290 - 1348)

With an HPI of 71.40, Andrea Pisano is the 7th most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 37 different languages.

Andrea Pisano (Pontedera 1290 – 1348 Orvieto) also known as Andrea da Pontedera, was an Italian sculptor and architect.

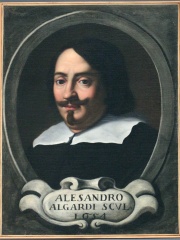

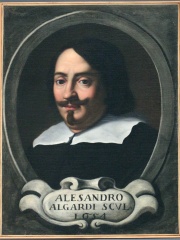

8. Alessandro Algardi (1595 - 1654)

With an HPI of 70.95, Alessandro Algardi is the 8th most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 37 different languages.

Alessandro Algardi (July 31, 1598 – June 10, 1654) was an Italian high-Baroque sculptor active almost exclusively in Rome. In the latter decades of his life, he was, along with Francesco Borromini and Pietro da Cortona, one of the major rivals of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, in Rome. He is now most admired for his portrait busts that have great vivacity and dignity.

9. Giovanni Pisano (1248 - 1315)

With an HPI of 70.18, Giovanni Pisano is the 9th most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 34 different languages.

Giovanni Pisano (c. 1250 – c. 1315) was an Italian sculptor, painter and architect, who worked in the cities of Pisa, Siena and Pistoia. He is best known for his sculpture which shows the influence of both the French Gothic and the Ancient Roman art. Henry Moore, referring to his statues for the facade of Siena Cathedral, called him "the first modern sculptor".

10. Jacopo della Quercia (1374 - 1438)

With an HPI of 68.13, Jacopo della Quercia is the 10th most famous Italian Sculptor. His biography has been translated into 33 different languages.

Jacopo della Quercia (, Italian: [ˈjaːkopo della ˈkwɛrtʃa]; c. 1374 – 20 October 1438), also known as Jacopo di Pietro d'Agnolo di Guarnieri, was an Italian sculptor of the Early Renaissance, a contemporary of Brunelleschi, Ghiberti and Donatello.

People

Pantheon has 37 people classified as Italian sculptors born between 600 BC and 1960. Of these 37, 2 (5.41%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Italian sculptors include Salvatore Garau, and Maurizio Cattelan. The most famous deceased Italian sculptors include Benvenuto Cellini, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Antonio Canova.

Living Italian Sculptors

Go to all RankingsDeceased Italian Sculptors

Go to all RankingsBenvenuto Cellini

1500 - 1571

HPI: 76.99

Lorenzo Ghiberti

1378 - 1455

HPI: 76.50

Antonio Canova

1757 - 1822

HPI: 76.37

Jacopo Sansovino

1486 - 1570

HPI: 71.91

Nicola Pisano

1225 - 1284

HPI: 71.85

Luca della Robbia

1399 - 1482

HPI: 71.48

Andrea Pisano

1290 - 1348

HPI: 71.40

Alessandro Algardi

1595 - 1654

HPI: 70.95

Giovanni Pisano

1248 - 1315

HPI: 70.18

Jacopo della Quercia

1374 - 1438

HPI: 68.13

Andrea della Robbia

1435 - 1525

HPI: 66.69

Bonanno Pisano

1150 - 1150

HPI: 65.74

Overlapping Lives

Which Sculptors were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 9 most globally memorable Sculptors since 1700.