The Most Famous

RELIGIOUS FIGURES from Belgium

This page contains a list of the greatest Belgian Religious Figures. The pantheon dataset contains 3,187 Religious Figures, 24 of which were born in Belgium. This makes Belgium the birth place of the 22nd most number of Religious Figures behind Syria, and Ukraine.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Belgian Religious Figures of all time. This list of famous Belgian Religious Figures is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Belgian Religious Figures.

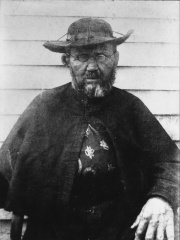

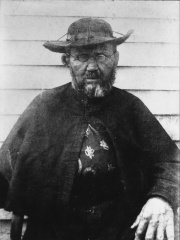

1. Father Damien (1840 - 1889)

With an HPI of 71.72, Father Damien is the most famous Belgian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 45 different languages on wikipedia.

Damien De Veuster , popularly known as Father Damien or Saint Damien of Molokai (Dutch: Pater Damiaan or Heilige Damiaan van Molokai; born Jozef De Veuster; 3 January 1840 – 15 April 1889), was a Belgian Catholic priest in the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary. He ministered to a leper colony in Molokaʻi, Kingdom of Hawaii, from 1873 until his death in 1889. De Veuster taught the Catholic faith to the people of Hawaii. He also cared for patients of leprosy (lepers) and established leaders within the community to build houses, schools, roads, hospitals, and churches. He dressed residents' ulcers, built a reservoir, made coffins, dug graves, shared pipes, and ate poi with them, providing both medical and emotional support. After 11 years caring for the physical, spiritual, and emotional needs of those in the leper colony, De Veuster contracted leprosy. He continued with his work until finally succumbing to the disease on 15 April 1889. He also had tuberculosis, which worsened his condition, but some believe the reason he volunteered in the first place was due to tuberculosis. De Veuster has been described as a "martyr of charity". De Veuster is considered the spiritual patron for lepers and outcasts. Father Damien Day, which takes place on the day of his death (April 15), is also a minor statewide holiday in Hawaii. De Veuster is the patron saint of the Diocese of Honolulu and of Hawaii. De Veuster was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI on 11 October 2009. Libert H. Boeynaems, writing in the Catholic Encyclopedia, calls him "the Apostle of the Lepers." De Veuster's feast day is 10 May.

2. Godfried Danneels (1933 - 2019)

With an HPI of 68.39, Godfried Danneels is the 2nd most famous Belgian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 29 different languages.

Godfried Maria Jules Danneels (4 June 1933 – 14 March 2019) was a Belgian Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Mechelen-Brussels and the chairman of the Episcopal Conference of Belgium from 1979 to 2010. He was elevated to the cardinalate in 1983.

3. Gertrude of Nivelles (626 - 659)

With an HPI of 68.36, Gertrude of Nivelles is the 3rd most famous Belgian Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 28 different languages.

Gertrude of Nivelles, OSB (also spelled Geretrude, Geretrudis, Gertrud; c. 628 – 17 March 659) was an abbess who, with her mother Itta, founded the Abbey of Nivelles, now in Belgium. She is venerated in the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions.

4. Bavo of Ghent (589 - 654)

With an HPI of 67.91, Bavo of Ghent is the 4th most famous Belgian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 24 different languages.

Saint Bavo of Ghent (also known as Bavon, Allowin, Bavonius, Baaf; AD 622–659) is a Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox saint. He exchanged a dissolute lifestyle for that of a missionary under the guidance of Saint Amand.

5. Gudula (b. 646)

With an HPI of 66.39, Gudula is the 5th most famous Belgian Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 18 different languages.

Gudula of Brabant, also known as Saint Gudula (ca. 646–712), was a Christian saint who is venerated in Catholic and Orthodox churches. In Brabant, she is usually called Goedele or Goule; (Latin: Gudila, later Gudula; Dutch: Goedele; French: Gudule). Her name is connected to several places: Moorsel (where she lived), Brussels (where a chapter in her honour was founded in 1047) and Eibingen (where the relic of her skull is conserved).

6. Juliana of Liège (1193 - 1258)

With an HPI of 65.77, Juliana of Liège is the 6th most famous Belgian Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 16 different languages.

Juliana of Liège (also called Juliana of Mount-Cornillon), (c. 1192 or 1193 – 5 April 1258) was a medieval Norbertine canoness regular and mystic in what is now Belgium. Traditional scholarly sources have long recognized her as the promoter of the Feast of Corpus Christi, first celebrated in Liège in 1246, and later adopted for the Catholic Church in 1264. More recent scholarship includes manuscript analysis of the initial version of the Office, as found in The Hague, National Library of the Netherlands (KB 70.E.4) and a close reading of her Latin vita, a critical edition of which was published in French by the Belgian scholar and current (2023) bishop of Liège, Jean-Pierre Delville. Newer scholarly work notes the many references to her musical and liturgical performances. Modern women scholars recognize Juliana as the "author" of the initial version of the Latin Office, Animarum cibus Archived 2023-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, which takes its title from the beginning of its first antiphon.

7. Begga (615 - 693)

With an HPI of 65.29, Begga is the 7th most famous Belgian Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 25 different languages.

Saint Begga (also Begue, Beghe, Begge) (615 – 17 December 693) was the daughter of Pepin of Landen, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, and his wife Itta. She is also the grandmother of Charles Martel, who is the grandfather of Charlemagne.

8. Lutgardis (1182 - 1246)

With an HPI of 64.88, Lutgardis is the 8th most famous Belgian Religious Figure. Her biography has been translated into 17 different languages.

Lutgardis of Aywières, OSB (Dutch: Sint-Ludgardis; 1182 – 16 June 1246; also spelled Lutgarde) was a Catholic Benedictine nun from the medieval Low Countries in the Holy Roman Empire. She was born in Tongeren, known as Tongres in French (which is why she is also called Lutgardis of Tongres or Luitgard of Tonger(e)n), and entered monastic life at the age of twelve. During her life, various miracles were attributed to her, and she is known to have experienced religious ecstasy. Her feast day is 16 June.

9. Jozef De Kesel (b. 1947)

With an HPI of 64.65, Jozef De Kesel is the 9th most famous Belgian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 22 different languages.

Jozef De Kesel (born 17 June 1947) is a Belgian Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Mechelen-Brussels from 2015 to 2023. He previously served there as auxiliary bishop from 2002 to 2010. He served as Bishop of Bruges from 2010 to 2015 and was made a cardinal in 2016.

10. Chrodegang (715 - 766)

With an HPI of 63.64, Chrodegang is the 10th most famous Belgian Religious Figure. His biography has been translated into 19 different languages.

Chrodegang (Latin: Chrodogangus; German: Chrodegang, Hruotgang; died 6 March 766) was the Frankish Bishop of Metz from 742 or 748 until his death. He served as chancellor for his kinsman, Charles Martel. Chrodegang is claimed to be a progenitor of the Frankish dynasty of the Robertians. He is recognized as a saint in the Catholic Church.

People

Pantheon has 24 people classified as Belgian religious figures born between 589 and 1963. Of these 24, 2 (8.33%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Belgian religious figures include Jozef De Kesel, and Dominique Mathieu. The most famous deceased Belgian religious figures include Father Damien, Godfried Danneels, and Gertrude of Nivelles. As of April 2024, 1 new Belgian religious figures have been added to Pantheon including Dominique Mathieu.

Living Belgian Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsDeceased Belgian Religious Figures

Go to all RankingsFather Damien

1840 - 1889

HPI: 71.72

Godfried Danneels

1933 - 2019

HPI: 68.39

Gertrude of Nivelles

626 - 659

HPI: 68.36

Bavo of Ghent

589 - 654

HPI: 67.91

Gudula

646 - Present

HPI: 66.39

Juliana of Liège

1193 - 1258

HPI: 65.77

Begga

615 - 693

HPI: 65.29

Lutgardis

1182 - 1246

HPI: 64.88

Chrodegang

715 - 766

HPI: 63.64

Clemens August of Bavaria

1700 - 1761

HPI: 63.63

William of St-Thierry

1085 - 1148

HPI: 63.49

Adalard of Corbie

751 - 827

HPI: 63.35

Newly Added Belgian Religious Figures (2025)

Go to all RankingsOverlapping Lives

Which Religious Figures were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 10 most globally memorable Religious Figures since 1700.