The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Vietnam

This page contains a list of the greatest Vietnamese Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 69 of which were born in Vietnam. This makes Vietnam the birth place of the 49th most number of Politicians behind Ireland, and Saudi Arabia.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Vietnamese Politicians of all time. This list of famous Vietnamese Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Vietnamese Politicians.

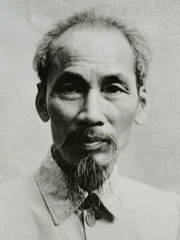

1. Ho Chi Minh (1890 - 1969)

With an HPI of 86.64, Ho Chi Minh is the most famous Vietnamese Politician. His biography has been translated into 126 different languages on wikipedia.

Hồ Chí Minh (born Nguyễn Sinh Cung; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), colloquially known as Uncle Ho (Bác Hồ) among other aliases and sobriquets, was a Vietnamese Marxist-Leninist revolutionary and politician who served as the founder and first president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam from 1945 until his death in 1969, and as its first prime minister from 1945 to 1955. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist, he founded the Indochinese Communist Party in 1930 and its successor Workers' Party of Vietnam (later the Communist Party of Vietnam) in 1951, serving as the party's chairman until his death. Hồ was born in Nghệ An province in French Indochina, and received a French education. Starting in 1911, he worked in various countries overseas, and in 1920 was a founding member of the French Communist Party in Paris. After studying in Moscow, Hồ founded the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League in 1925, which he transformed into the Indochinese Communist Party in 1930. On his return to Vietnam in 1941, he founded and led the Việt Minh independence movement against the Japanese, and in 1945 led the August Revolution against the monarchy and proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. After the French returned to power, Hồ's government retreated to the countryside and initiated guerrilla warfare from 1946. Between 1953 and 1956, Hồ's leadership saw the implementation of a land reform campaign, which included executions and political purges. The Việt Minh defeated the French in 1954 at the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ, ending the First Indochina War. At the 1954 Geneva Conference, Vietnam was divided into two de facto separate states, with the Việt Minh in control of North Vietnam, and anti-communists backed by the United States in control of South Vietnam. Hồ remained president and party leader during the Vietnam War, which began in 1955. He supported the Viet Cong insurgency in the south, overseeing the transport of troops and supplies on the Ho Chi Minh trail until his death in 1969. North Vietnam won in 1975, and the country was re-unified in 1976 as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Saigon – Gia Định, South Vietnam's former capital, was renamed Ho Chi Minh City in his honor. The details of Hồ's life before he came to power in Vietnam are uncertain. He is known to have used between 50 and 200 pseudonyms. Information on his birth and early life is ambiguous and subject to academic debate. At least four existing official biographies vary on names, dates, places, and other hard facts while unofficial biographies vary even more widely. Aside from being a politician, Hồ was a writer, poet, and journalist. He wrote several books, articles, and poems in Chinese, Vietnamese, and French.

2. Ngo Dinh Diem (1901 - 1963)

With an HPI of 76.40, Ngo Dinh Diem is the 2nd most famous Vietnamese Politician. His biography has been translated into 63 different languages.

Ngô Đình Diệm ( dyem, YEE-əm or zeem; Vietnamese: [ŋō ɗìn jîəmˀ] ; 3 January 1901 – 2 November 1963) was a South Vietnamese politician who was the final prime minister of the State of Vietnam (1954–1955) and later the first president of South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) from 1955 until his capture and assassination during the CIA-backed 1963 coup d'état. Diệm was born into a prominent Catholic family with his father, Ngô Đình Khả, being a high-ranking mandarin for Emperor Thành Thái during the French colonial era. Diệm was educated at French-speaking schools and considered following his brother Ngô Đình Thục into the priesthood, but eventually chose to pursue a career in the civil service. He progressed rapidly in the court of Emperor Bảo Đại, becoming governor of Bình Thuận Province in 1929 and interior minister in 1933. However, he resigned from the latter position after three months and publicly denounced the emperor as a tool of France. Diệm came to support Vietnamese nationalism, promoting both anti-communism, in opposition to Ho Chi Minh, and decolonization, in opposition to Bảo Đại. He established the Cần Lao Party to support his political doctrine of Person Dignity Theory, which was a blend of the philosophies of Personalism, especially as understood by French philosopher Emmanuel Mounier, and of Confucianism, which Diệm and his father had greatly admired. Diệm supported the Confucian concept of "Mandate of Heaven", and wished to make it the basis of political theory that would emerge in Vietnam. After several years in exile in Japan, the United States, and Europe, Diệm returned home in July 1954 and was appointed prime minister by Bảo Đại, against the French suggestion of Nguyen Ngoc Bich (a French-educated engineer, Francophile anticolonialist, a resistance hero in the First Indochina War, and medical doctor) as an alternative. The 1954 Geneva Conference took place soon after he took office, formally partitioning Vietnam along the 17th parallel. Diệm, with the aid of his younger brother Ngô Đình Nhu, soon consolidated power in South Vietnam. After the 1955 State of Vietnam referendum, he proclaimed the creation of the Republic of Vietnam, with himself as president. His government was supported by other anti-communist countries, most notably the United States. Diệm pursued a series of nation-building projects, promoting industrial and rural development. From 1957 onward, as part of the Vietnam War, he faced a communist insurgency backed by North Vietnam, eventually formally organized under the banner of the Viet Cong. He was subject to several assassination and coup attempts, and in 1962 established the Strategic Hamlet Program as the cornerstone of his counterinsurgency effort. In 1963, Diệm's favoritism towards Catholics and persecution of practitioners of Buddhism in Vietnam led to the Buddhist crisis. The event damaged relations with the United States and other previously sympathetic countries, and his organization lost favor with the leadership of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. On 1 November 1963, the country's leading generals launched a coup d'état with assistance from the Central Intelligence Agency. Diệm and his brother, Nhu, initially escaped, but were recaptured the following day and assassinated on the orders of Dương Văn Minh, who succeeded him as president. Diệm has been a controversial historical figure. Some have considered him a tool of the United States, while others portrayed him as an avatar of Vietnamese tradition. At the time of his assassination, Western media widely considered him a dictator, though South Vietnamese offered a variety of views, generally acknowledging that he strongly opposed American interference.

3. Bảo Đại (1913 - 1997)

With an HPI of 74.74, Bảo Đại is the 3rd most famous Vietnamese Politician. His biography has been translated into 54 different languages.

Bảo Đại (Vietnamese: [ɓâw ɗâjˀ], chữ Hán: 保大, lit. "keeper of greatness", 22 October 1913 – 31 July 1997), born Nguyễn Phúc (Phước) Vĩnh Thụy (chữ Hán: 阮福永瑞), was the 13th and final emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty, the last ruling dynasty of Vietnam. From 1926 to 1945, he was de jure emperor of Annam and Tonkin, which were then protectorates in French Indochina, covering the present-day central and northern Vietnam. Bảo Đại ascended the throne in 1932. The Japanese ousted the Vichy French administration in March 1945 and ruled through Bảo Đại, who proclaimed the Empire of Vietnam. He abdicated in August 1945 after Japan surrendered. From 1949 to 1955, Bảo Đại was the chief of state of the anti-communist State of Vietnam. Viewed as a puppet ruler, Bảo Đại was criticized for being too closely associated with France and spending much of his time outside Vietnam. He was eventually ousted in a referendum in 1955 by Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm, who was supported by the United States.

4. Lady Sun (b. 192)

With an HPI of 69.23, Lady Sun is the 4th most famous Vietnamese Politician. Her biography has been translated into 21 different languages.

Lady Sun (fl.180s – 211), also known as Sun Ren in the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Sun Shangxiang in Chinese opera and modern popular culture, was a Chinese noblewoman who lived during the late Eastern Han dynasty. She was a daughter of the warlord Sun Jian, and her (known) older brothers were the warlords Sun Ce and Sun Quan, who founded the state of Eastern Wu in the Three Kingdoms period. Sometime in 209, she married the warlord Liu Bei to strengthen an alliance between Liu Bei and Sun Quan. Around 211, she returned to Sun Quan's domain when Liu Bei left Jing Province (covering present-day Hubei and Hunan) and settled in Yi Province (covering present-day Sichuan and Chongqing).

5. Ieng Sary (1925 - 2013)

With an HPI of 69.21, Ieng Sary is the 5th most famous Vietnamese Politician. His biography has been translated into 33 different languages.

Ieng Sary (Khmer: អៀង សារី; born Kim Trang; 24 October 1925 – 14 March 2013) was the co-founder and a senior member of the Khmer Rouge and one of the main architects of the Cambodian genocide. He was a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kampuchea led by Pol Pot and served in the 1975–79 government of Democratic Kampuchea as foreign minister and deputy prime minister. He was known as "Brother Number Three", as he was third in command after Pol Pot and Nuon Chea. His wife, Ieng Thirith (née Khieu), served in the Khmer Rouge government as social affairs minister. Ieng Sary was arrested in 2007 and was charged with crimes against humanity but died of heart failure before the case against him could be brought to a verdict.

6. Kaysone Phomvihane (1920 - 1992)

With an HPI of 69.13, Kaysone Phomvihane is the 6th most famous Vietnamese Politician. His biography has been translated into 34 different languages.

Kaysone Phomvihane (Kraisorn Brahmavihara; Lao: ໄກສອນ ພົມວິຫານ, pronounced [kàj.sɔ̌ːn pʰóm.wī(ʔ).hǎːn]; 13 December 1920 – 21 November 1992) was the first leader of the Communist Lao People's Revolutionary Party from 1955 until his death in 1992. After the Communists seized power in the wake of the Laotian Civil War, he was the de facto leader of Laos from 1975 until his death. He served as the first Prime Minister of the Lao People's Democratic Republic from 1975 to 1991 and then as the second President from 1991 to 1992. His theories and policies are officially known as Kaysone Phomvihane Thought.

7. Nguyễn Văn Thiệu (1923 - 2001)

With an HPI of 68.38, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu is the 7th most famous Vietnamese Politician. His biography has been translated into 38 different languages.

Nguyễn Văn Thiệu (Vietnamese: [ŋʷǐənˀ vān tʰîəwˀ] ; 5 April 1923 – 29 September 2001) was a South Vietnamese military officer and politician who was the president of South Vietnam from 1967 to 1975. He was a general in the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF), became head of a military junta in 1965, and then president after winning a rigged election in 1967. He headed the government of South Vietnam until he resigned and left the nation and relocated to Taipei a few days before the fall of Saigon and the ultimate North Vietnamese victory. Born in Phan Rang in the south central coast of Vietnam, Thieu joined the communist-dominated Việt Minh of Hồ Chí Minh in 1945 but quit after a year and joined the Vietnamese National Army (VNA) of the French-backed State of Vietnam. He gradually rose up the ranks and, in 1954, led a battalion in expelling the communists from his native village. Following the withdrawal of France, the VNA became the ARVN and Thiệu was the head of the Vietnamese National Military Academy for four years before becoming a division commander and colonel. In November 1960, he helped put down a coup attempt against President Ngô Đình Diệm. During this time, he also converted to Catholicism and joined the regime's secret Cần Lao Party; Diệm was thought to give preferential treatment to his co-religionists and Thiệu was accused of being one of many who converted for political advancement. Despite this, Thiệu agreed to join the coup against Ngô Đình Diệm in November 1963 in the midst of the Buddhist crisis, leading the siege on Gia Long Palace. Diệm was captured and executed and Thiệu made a general. Following Diệm's death, there were several short-lived juntas as coups occurred frequently. Thiệu gradually moved up the ranks of the junta by adopting a cautious approach while other officers around him defeated and sidelined one another. In 1965, stability came to South Vietnam when he became the nominal head of state and Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ became prime minister, although the men were rivals. In 1967, a transition to elected government was scheduled; and, after a power struggle within the military, Thiệu ran for the presidency with Kỳ as his running mate—both men had wanted the top job. To allow the two to work together, their fellow officers had agreed to have a military body controlled by Kỳ shape policy behind the scenes. Leadership tensions became evident, and Thiệu prevailed, sidelining Kỳ supporters from key military and cabinet posts. Thiệu then passed legislation to restrict candidacy eligibility for the 1971 election, banning almost all would-be opponents, while the rest withdrew as it was obvious that the poll would be a sham; Thiệu won 100% of the vote and the election was uncontested, while Kỳ retired from politics. During his rule, Thiệu was accused of turning a blind eye to and indulging in corruption, and appointing loyalists rather than competent officers to lead ARVN units. During the 1971 Operation Lam Sơn 719 and the communists' Easter Offensive, the I Corps in the north of the country was under the command of his confidant, Hoàng Xuân Lãm, whose incompetence led to heavy defeats until Thiệu finally replaced him with Ngô Quang Trưởng. After the signing of the Paris Peace Accords—which Thiệu opposed—and the US withdrawal, South Vietnam resisted the communists for another two years until the communists' final push for victory, which saw the South openly invaded by the entire North Vietnamese army. Thiệu gave contradictory orders to Trưởng to stand and fight or withdraw and consolidate, leading to mass panic and collapse in the south of the country. This allowed the communists to generate much momentum and within a month they were close to Saigon, prompting Thiệu to resign and leave the country. He eventually settled near Boston, Massachusetts, preferring not to talk to the media. He died in 2001. Thiệu has been described as dictatorial, similar to Ngô Đình Diệm.

8. Nguyễn Phú Trọng (1944 - 2024)

With an HPI of 68.27, Nguyễn Phú Trọng is the 8th most famous Vietnamese Politician. His biography has been translated into 59 different languages.

Nguyễn Phú Trọng (Vietnamese: [ŋwiən˦ˀ˥ fu˧˦ t͡ɕawŋ͡m˧˨ʔ] new-yen foo chong; 14 April 1944 – 19 July 2024) was a Vietnamese politician and political theorist who served as general secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam from 2011 until his death in 2024. As the head of the party's Secretariat, Politburo and Central Military Commission, Trọng was Vietnam's paramount leader. From 2018 to 2021, he also served concurrently as the tenth president of Vietnam. A conservative Marxist–Leninist, Trọng joined the Communist Party of Vietnam in 1967 and rose through the section devoted to political work. He later joined the party's Central Committee in 1994, its Politburo in 1997 and Vietnam's National Assembly in 2002. Between 2000 and 2006, he was the Party Secretary for Hanoi, effectively the city's highest-ranking position. He served as Chairman of the National Assembly from 2006 to 2011. Trọng rose to the general secretaryship at the party's 11th National Congress in 2011 and was re-elected at the 12th National Congress in 2016. He became state president in 2018 following the death of President Trần Đại Quang, becoming the third person to simultaneously head the party and state after Hồ Chí Minh (in North Vietnam only) and Trường Chinh. At the 13th National Congress in 2021, he was re-elected as general secretary, becoming the third leader of Vietnam to secure a third term (after Hồ Chí Minh and Lê Duẩn), and was succeeded by Nguyễn Xuân Phúc as president. During his tenure, Trọng pursued a wide anti-corruption campaign, implicating numerous senior officials to a degree unprecedented in Vietnamese political history. His foreign policy, known as bamboo diplomacy, sought to balance Vietnam's relations with both the United States and China. He presided over a period of rapid economic growth. Trọng is considered one of the most influential Vietnamese leaders since Hồ Chí Minh.

9. Lê Duẩn (1907 - 1986)

With an HPI of 67.62, Lê Duẩn is the 9th most famous Vietnamese Politician. His biography has been translated into 40 different languages.

Lê Duẩn (Vietnamese: [lē zʷə̂n]; 7 April 1907 – 10 July 1986) was a Vietnamese communist politician. He rose in the party hierarchy in the late 1950s and became General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam (VCP) at the 3rd National Congress in 1960. When Ho Chi Minh died in 1969, he consolidated power to become the undisputed leader of North Vietnam. Upon defeating South Vietnam in the Second Indochina War in 1975, he subsequently ruled the newly unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam from 1976 until his death in 1986. He was born into a lower-class family in Quảng Trị Province, in the Annam Protectorate of French Indochina as Lê Văn Nhuận. Little is known about his family and childhood. He first came in contact with revolutionary thoughts in the 1920s through his work as a railway clerk. Lê Duẩn was a founding member of the Indochina Communist Party (the future Communist Party of Vietnam) in 1930. He was imprisoned in 1931 and released in 1937. From 1937 to 1939, he climbed the party ladder. He was rearrested in 1939, this time for fomenting an uprising in the South. Lê Duẩn was released from jail following the successful Communist-led August Revolution of 1945. During the First Indochina War (1946-1954), Lê Duẩn was an active revolutionary leader in South Vietnam. He headed the Central Office of South Vietnam, a Party organ, from 1951 until 1954. During the 1950s, Lê Duẩn became increasingly aggressive towards South Vietnam and called for reunification through war. By the mid-to-late 1950s, Lê Duẩn had become the second-most powerful policy-maker within the Party, eclipsing former Party First Secretary Trường Chinh. By 1960, he was officially the second-most powerful Party member, after Party chairman Hồ. Throughout the 1960s, Hồ's health declined, and Lê Duẩn assumed more of his responsibilities. Following Hồ's death in 1969, Lê Duẩn assumed leadership of North Vietnam. Throughout the Second Indochina War (1955–1975). When South Vietnam was reunited with North Vietnam in 1976, he assumed the new title of General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam. Later in December 1978, Lê Duẩn oversaw the Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia, which ultimately led to the fall of the Chinese-backed Khmer Rouge on 7 January 1979. This had a serious impact on relations between Vietnam and China, with Vietnam responding with a period of deportation of ethnic Chinese Hoa people. China invaded the northern Vietnamese border, which was to be known as the Sino-Vietnamese War in 1979, though it was short-lived and remained inconclusive. From then on, Vietnam maintained a closer alliance with the Soviet Union and joined Comecon in 1978. Lê remained General Secretary until he died in 1986. He died in Hanoi; his successor was initially Trường Chinh. Lê Duẩn was also known as Lê Dung and was known in public as "anh Ba" (third brother).

10. Dương Văn Minh (1916 - 2001)

With an HPI of 67.07, Dương Văn Minh is the 10th most famous Vietnamese Politician. His biography has been translated into 35 different languages.

Dương Văn Minh (Vietnamese: [jɨəŋ van miŋ̟] or [zɨəŋ van miŋ̟]; 16 February 1916 – 6 August 2001), popularly known as Big Minh, was a South Vietnamese politician and a senior general in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and a politician during the presidency of Ngô Đình Diệm. In 1963, he became chief of a military junta after leading a coup in which Diệm was assassinated. Minh lasted only three months before being toppled by Nguyễn Khánh, but assumed power again as the fourth and last President of South Vietnam in April 1975, two days before surrendering to North Vietnamese forces. He earned his nickname "Big Minh", because he was approximately 1.83 m (6 ft) tall and weighed 90 kg (198 lb). Born in Tiền Giang province in the Mekong Delta region of southern Vietnam, Minh joined the French Army at the start of World War II, and was captured and tortured by the Imperial Japanese, who invaded and seized French Indochina. After his release, he joined the French-backed Vietnamese National Army (VNA) and was imprisoned by the communist-dominated Viet Minh before breaking out. In 1955, after Vietnam was partitioned and the State of Vietnam controlled the southern half under Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm, Minh led the VNA in decisively defeating the Bình Xuyên paramilitary crime syndicate in street combat and dismantling the Hòa Hảo religious tradition's private army. This made him popular with the people and Diệm, but the latter later put him in a powerless position, regarding him as a threat. In 1963, the authoritarian Diệm became increasingly unpopular due to the Buddhist crisis and the ARVN generals decided to launch a coup, which Minh eventually led. Diệm was assassinated on 2 November 1963 shortly after being deposed. Minh was accused of ordering an aide, Nguyễn Văn Nhung, to kill Diệm. Minh then led a junta for three months, but he was an unsuccessful leader and was heavily criticized for being lethargic and uninterested. During his three months of rule, many civilian problems intensified and the communist Viet Cong made significant gains. Angered at not receiving his desired post, General Nguyễn Khánh led a group of similarly motivated officers in a January 1964 coup. Khánh allowed Minh to stay on as a token head of state in order to capitalize on Minh's public standing, but retained real power. After a power struggle, Khanh had Minh exiled. Minh stayed away before deciding to return and challenge General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu in the presidential election of 1971. When it became obvious that Thieu would rig the poll, Minh withdrew and did not return until 1972, keeping a low profile. Minh then advocated a "third force", maintaining that Vietnam could be reunified without a military victory to a hardline communist or anti-communist government. However, this was not something that Thiệu agreed with. In April 1975, as South Vietnam was on the verge of being overrun, Thieu resigned. A week later, Minh was forcibly chosen by the legislature and became president on 28 April. Saigon fell two days later on 30 April, and Minh ordered a surrender to prevent bloody urban street fighting. Minh was spared the lengthy incarceration meted out to South Vietnamese military personnel and civil servants, and lived quietly until being allowed to emigrate to France in 1983. He later moved to California, in the US, where he died.

People

Pantheon has 69 people classified as Vietnamese politicians born between 192 and 1978. Of these 69, 14 (20.29%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Vietnamese politicians include Nguyễn Minh Triết, Phạm Minh Chính, and Trương Tấn Sang. The most famous deceased Vietnamese politicians include Ho Chi Minh, Ngo Dinh Diem, and Bảo Đại.

Living Vietnamese Politicians

Go to all RankingsNguyễn Minh Triết

1942 - Present

HPI: 62.97

Phạm Minh Chính

1958 - Present

HPI: 62.97

Trương Tấn Sang

1949 - Present

HPI: 62.70

Nguyễn Xuân Phúc

1954 - Present

HPI: 61.48

Nguyễn Tấn Dũng

1949 - Present

HPI: 60.40

Nông Đức Mạnh

1939 - Present

HPI: 58.23

Đặng Thị Ngọc Thịnh

1959 - Present

HPI: 57.37

Võ Thị Ánh Xuân

1970 - Present

HPI: 53.74

Võ Văn Thưởng

1970 - Present

HPI: 52.95

Philipp Rösler

1973 - Present

HPI: 52.53

Nguyễn Thị Kim Ngân

1954 - Present

HPI: 51.83

Stephanie Murphy

1978 - Present

HPI: 47.88

Deceased Vietnamese Politicians

Go to all RankingsHo Chi Minh

1890 - 1969

HPI: 86.64

Ngo Dinh Diem

1901 - 1963

HPI: 76.40

Bảo Đại

1913 - 1997

HPI: 74.74

Lady Sun

192 - Present

HPI: 69.23

Ieng Sary

1925 - 2013

HPI: 69.21

Kaysone Phomvihane

1920 - 1992

HPI: 69.13

Nguyễn Văn Thiệu

1923 - 2001

HPI: 68.38

Nguyễn Phú Trọng

1944 - 2024

HPI: 68.27

Lê Duẩn

1907 - 1986

HPI: 67.62

Dương Văn Minh

1916 - 2001

HPI: 67.07

Hanoi Hannah

1931 - 2016

HPI: 66.11

Gia Long

1762 - 1820

HPI: 65.61

Overlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.