The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Belarus

This page contains a list of the greatest Belarusian Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 67 of which were born in Belarus. This makes Belarus the birth place of the 51st most number of Politicians behind Vietnam, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Belarusian Politicians of all time. This list of famous Belarusian Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Belarusian Politicians.

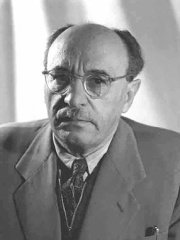

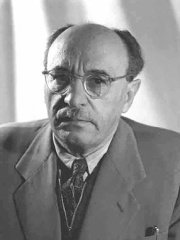

1. Shimon Peres (1923 - 2016)

With an HPI of 80.51, Shimon Peres is the most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 96 different languages on wikipedia.

Shimon Peres ( shee-MOHN PERR-ess, -ez; Hebrew: שמעון פרס [ʃiˌmon ˈpeʁes] ; born Szymon Perski, Polish: [ˈʂɨmɔn ˈpɛrskʲi]; 2 August 1923 – 28 September 2016) was an Israeli politician and statesman who served as the prime minister of Israel from 1984 to 1986 and from 1995 to 1996 and as the president of Israel from 2007 to 2014. He was a member of twelve cabinets and represented five political parties in a political career spanning 70 years. Peres was elected to the Knesset in November 1959 and except for three months out of office in early 2006, served as a member of the Knesset continuously until he was elected president in 2007. Serving in the Knesset for 48 years (with the first uninterrupted stretch lasting more than 46 years), Peres is the longest serving member in the Knesset's history. At the time of his retirement from politics in 2014, he was the world's oldest head of state and was considered the last link to Israel's founding generation, as well as the last Prime Minister to make aliyah rather than being born on territory that would become Israel. From a young age, he was renowned for his oratorical brilliance, and was chosen as a protégé by David Ben-Gurion, Israel's founding father. He began his political career in the late 1940s, holding several diplomatic and military positions during and directly after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. His first high-level government position was as deputy director general of defense in 1952 which he attained at the age of 28, and director general from 1953 until 1959. In 1956, he took part in the historic negotiations on the Protocol of Sèvres, which was described by British prime minister Anthony Eden as the "highest form of statesmanship". In 1963, he held negotiations with U.S. president John F. Kennedy, which resulted in the sale of Hawk anti-aircraft missiles to Israel, the first sale of U.S. military equipment to Israel. Peres represented Mapai, Rafi, the Alignment, Labor and Kadima in the Knesset, and led Alignment and Labor. Peres first succeeded Yitzhak Rabin as acting prime minister briefly during 1977, before becoming prime minister from 1984 to 1986. As foreign minister under Prime Minister Rabin, Peres engineered the 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty, and won the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize together with Rabin and Yasser Arafat for the Oslo Accords peace talks with the Palestinian leadership. In 1996, he founded the Peres Center for Peace, which has the aim of "promot[ing] lasting peace and advancement in the Middle East by fostering tolerance, economic and technological development, cooperation and well-being." After suffering a stroke, Peres died in 2016 near Tel Aviv.

2. Alexander Lukashenko (b. 1954)

With an HPI of 79.35, Alexander Lukashenko is the 2nd most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 126 different languages.

Alexander Grigoryevich Lukashenko (also transliterated from Belarusian as Alyaksandr Ryhoravich Lukashenka; born 30 August 1954) is a Belarusian politician who has been the first and only president of Belarus since the office's establishment in 1994, making him the current longest-serving European leader. Before embarking on his political career, Lukashenko worked as the director of a state farm (sovkhoz) and served in both the Soviet Border Troops and the Soviet Army. In 1990, Lukashenko was elected to the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, he assumed the position of head of the interim anti-corruption committee of the Supreme Council of Belarus. In 1994, he won the presidency in the country's inaugural presidential election after the adoption of a new constitution. Lukashenko opposed economic shock therapy during the 1990s post-Soviet transition, maintaining state ownership of key industries in Belarus. His supporters claim this spared Belarus from recessions as devastating as those in other post-Soviet states, whose political structures devolved into oligarchic crony capitalism. Lukashenko's maintenance of the socialist economic model is consistent with the retention of Soviet-era symbolism, including the Russian language, coat of arms, and national flag. These symbols were adopted after a controversial 1995 referendum. Following the same referendum, Lukashenko acquired increased power, including the authority to dismiss the Supreme Council. Another referendum in 1996 further facilitated his consolidation of power. Lukashenko has since presided over an authoritarian government and has commonly been labeled as "Europe's last dictator". International monitors have not considered Belarusian elections as free and fair, except for his initial win. Additionally, the government harshly suppresses opponents and limits media freedom. Eventually, this has led multiple Western governments to impose sanctions on Lukashenko and other Belarusian officials. Lukashenko's contested victory in the 2020 presidential election preceded allegations of vote-rigging, amplifying anti-government protests, the largest seen during his rule. Consequently, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and the United States ceased to recognise Lukashenko as the legitimate president of Belarus following the disputed election. Lukashenko remained in power, which eventually led to a resumption of partial diplomatic relations. His re-election in the 2025 presidential election was described as a sham by the opposition and the European parliament. Such isolation from parts of the West has, especially in the Putin era, increased his dependence on Russia, with whom Lukashenko had already maintained close ties despite past tensions, such as the so-called Milk War in 2009, stemming from Belarus' refusal to recognize the republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in exchange for $500 million, in the aftermath of the Russo-Georgian War. Lukashenko played a crucial role in creating the Union State, enabling Belarusians and Russians to travel, work, and study unhindered between the two countries. He also reportedly played a crucial role in brokering a deal to end the Russian Wagner Group rebellion in 2023, allowing some Wagner soldiers to cross the country's border unhindered and settle in Belarus.

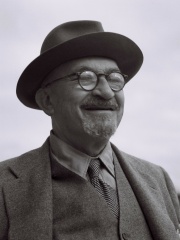

3. Menachem Begin (1913 - 1992)

With an HPI of 77.55, Menachem Begin is the 3rd most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 81 different languages.

Menachem Begin (16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician who founded Herut and Likud and served as prime minister of Israel from 1977 to 1983. Before the creation of the state of Israel, Begin was the leader of the Zionist militant group Irgun, the Revisionist breakaway from the larger Jewish paramilitary organization Haganah. He proclaimed a revolt, on 1 February 1944, against the British mandatory government, which was opposed by the Jewish Agency. As head of the Irgun, he targeted the British in Palestine, with a notable attack being the King David Hotel bombing. Later, the Irgun fought the Arabs during the 1947–48 civil war in Mandatory Palestine and, as its chief, Begin was described by the British government as the "leader of the notorious terrorist organisation". It declined him an entry visa to the United Kingdom between 1953 and 1955. However, Begin's overtures of friendship eventually paid off and he was granted a visa in 1972, five years prior to becoming prime minister. Begin was elected to the first Knesset, as head of Herut, the party he founded, and was at first on the political fringe, embodying the opposition to the Mapai-led government and Israeli establishment. He remained in opposition in the eight consecutive elections (except for a national unity government around the Six-Day War), but became more acceptable to the political center. His 1977 electoral victory and premiership ended three decades of Labor Party political dominance. Begin's most significant achievement as prime minister was the signing of a peace treaty with Egypt in 1979, for which he and Anwar Sadat shared the Nobel Peace Prize. In the wake of the Camp David Accords, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula, which had been captured from Egypt in the Six-Day War. Later, Begin's government promoted the construction of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Begin authorized the bombing of the Osirak nuclear plant in Iraq and the invasion of Lebanon in 1982 to fight Palestine Liberation Organization strongholds there, igniting the 1982 Lebanon War. As Israeli military involvement in Lebanon deepened, and the Sabra and Shatila massacre, carried out by Christian Phalangist militia allies of the Israelis, shocked world public opinion, Begin grew increasingly isolated. As IDF forces remained mired in Lebanon and the economy suffered from hyperinflation, the public pressure on Begin mounted. Depressed by the death of his wife Aliza in November 1982, he gradually withdrew from public life, until his resignation in October 1983.

4. Felix Dzerzhinsky (1877 - 1926)

With an HPI of 76.33, Felix Dzerzhinsky is the 4th most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 65 different languages.

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky (Russian: Феликс Эдмундович Дзержинский; Polish: Feliks Edmundowicz Dzierżyński [ˈfɛliks ɛdmundɔvʲiʈ͡ʂ d͡ʑɛrʐɨj̃skʲi]; 11 September [O.S. 30 August] 1877 – 20 July 1926), nicknamed Iron Felix (Russian: Железный Феликс), was a Soviet revolutionary and politician of Polish origin. From 1917 until his death in 1926, he led the first three Soviet secret police organizations, the Cheka, the GPU and the OGPU, establishing state security organs for the Bolshevik government. He was a key architect of the Red Terror and de-Cossackization. Born to a Polish family of noble descent in their Ozhyemblovo Estate (in 1881 named Dzerzhinovo), in Russian Poland, Dzerzhinsky embraced revolutionary politics from a young age, and was active in the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania party. Active in Kaunas and Warsaw, he was frequently arrested and underwent several exiles to Siberia, from which he escaped every time. He evaded the tsarist secret police, the Okhrana, whose work he took interest in. Dzerzhinsky participated in the failed 1905 Revolution, and after a final arrest in 1912, was imprisoned until the February Revolution of 1917. He then joined Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik party, and played an active role in the October Revolution which brought them to power. In December 1917, Lenin named Dzerzhinsky head of the newly established All-Russian Extraordinary Commission (Cheka), tasking him with the suppression of counter-revolutionary activities in Soviet Russia. The Russian Civil War saw a vast expansion of the Cheka's authority, inaugurating a campaign of mass arrests, detentions (including in newly founded Gulag forced labour camps), and executions known as the Red Terror. An estimated 50,000 to 200,000 people were executed by the Cheka during the years of the civil war. The agency was reorganized as the State Political Directorate (GPU) in 1922, and then as the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) a year later, with Dzerzhinsky remaining as head of the powerful organization. He served as director of the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy (VSNKh) from 1924. Dzerzhinsky died of a heart attack in 1926, and was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis. He was remembered by secret police agents (known as "Chekists" throughout the Soviet era) as a hero of the revolution. A large statue of him stood in front of the security service headquarters at Moscow's Lubyanka Building until 1991. He also became a prominent symbol of repression and brutality to critics of the Soviet Union.

5. Chaim Weizmann (1874 - 1952)

With an HPI of 75.25, Chaim Weizmann is the 5th most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 61 different languages.

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( KYME WYTES-mən; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born Israeli statesman, biochemist, and Zionist leader who served as president of the Zionist Organization and later as the first president of Israel. He was elected on 16 February 1949, and served until his death in 1952. Weizmann was instrumental in obtaining the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and convincing the United States government to recognize the newly formed State of Israel in 1948. As a biochemist, Weizmann is considered to be the 'father' of industrial fermentation. He developed the acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation process, which produces acetone, n-butanol and ethanol through bacterial fermentation. His acetone production method was of great importance in the manufacture of cordite explosive propellants for the British war industry during World War I. He founded the Sieff Research Institute in Rehovot (later renamed the Weizmann Institute of Science in his honor), and was instrumental in the establishment of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

6. Andrei Gromyko (1909 - 1989)

With an HPI of 74.94, Andrei Gromyko is the 6th most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 67 different languages.

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko (18 July [O.S. 5 July] 1909 – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as Minister of Foreign Affairs (1957–1985) and as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (1985–1988). Gromyko was responsible for many top decisions on Soviet foreign policy until he retired in 1988. In the 1940s, Western pundits called him Mr. Nyet ("Mr. No"), or Grim Grom, because of his frequent use of the Soviet veto in the United Nations Security Council. Gromyko's political career started in 1939 in the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs (renamed Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1946). He became the Soviet ambassador to the United States in 1943, leaving that position in 1946 to become the Soviet Permanent Representative to the United Nations in New York. Upon his return to Moscow he became a Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and later First Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and eventually Foreign Minister. He went on to become the Soviet ambassador to the United Kingdom in 1952. As Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union, Gromyko was directly involved in deliberations with the Americans during the Cuban Missile Crisis and helped broker a peace treaty ending the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War. Under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev, he played a central role in the establishment of détente with the United States by negotiating the ABM Treaty, the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and the SALT I & II, among others. As Brezhnev's health deteriorated from the mid-1970s onward, Gromyko began to increasingly dictate Soviet policy alongside Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov and KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov. Even after Brezhnev's death in 1982, Gromyko's rigid conservatism and distrust of the West continued to underlie the Soviet Union's foreign policy until Mikhail Gorbachev's rise to power in 1985. Upon Konstantin Chernenko's selection as General Secretary on 13 February 1984, Andrei Gromyko formed an unofficial triumvirate alongside Ustinov and Chernenko that governed the Soviet Union through the end of the year. However, following Gorbachev's election as General Secretary in March 1985, Gromyko was removed from office as foreign minister and appointed to the largely ceremonial post of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. He ultimately retired from political life in 1988, and died the following year in Moscow.

7. Stanisław August Poniatowski (1732 - 1798)

With an HPI of 74.82, Stanisław August Poniatowski is the 7th most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 57 different languages.

Stanisław II August (born Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski; 17 January 1732 – 12 February 1798), known also by his regnal Latin name Stanislaus II Augustus, and as Stanisław August Poniatowski (Lithuanian: Stanislovas Augustas Poniatovskis), was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1764 to 1795, and the last monarch of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Born into wealthy Polish aristocracy, Poniatowski arrived as a diplomat at the Russian imperial court in Saint Petersburg in 1755 at the age of 22 and became intimately involved with the future empress Catherine the Great. With her aid, he was elected King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania by the Sejm in September 1764 following the death of Augustus III. Contrary to expectations, Poniatowski attempted to reform and strengthen the large but ailing Commonwealth. His efforts were met with external opposition from neighbouring Prussia, Russia and Austria, all committed to keeping the Commonwealth weak. From within he was opposed by conservative interests, which saw the reforms as a threat to their traditional liberties and privileges granted centuries earlier. The defining crisis of his early reign was the War of the Bar Confederation (1768–1772) that led to the First Partition of Poland (1772). The later part of his reign saw reforms wrought by the Diet (1788–1792) and the Constitution of 3 May 1791. These reforms were overthrown by the 1792 Targowica Confederation and by the Polish–Russian War of 1792, leading directly to the Second Partition of Poland (1793), the Kościuszko Uprising (1794) and the final and Third Partition of Poland (1795), marking the end of the Commonwealth. Stripped of all meaningful power, Poniatowski abdicated in November 1795 and spent the last years of his life as a captive in Saint Petersburg's Marble Palace. A controversial figure in Poland's history, he is viewed with ambivalence as a brave and skillful statesman by some and as an overly hesitant coward by others, and even as a traitor. He is criticized primarily for his failure to resolutely stand against opposing forces and prevent the partitions, which led to the destruction of the Polish state. On the other hand, he is remembered as a great patron of arts and sciences who laid the foundation for the Commission of National Education, the first institution of its kind in the world, the Great Sejm of 1788–1792, which led to the Constitution of 3 May 1791 and as a sponsor of many architectural landmarks. Historians tend to agree that, taking the circumstances into account, he was a skillful statesman, pointing out that passing the Constitution was a sign of bravery, although his unwillingness to organize a proper nationwide uprising afterward is seen as cowardice and the key reason for the Second Partition and the subsequent downfall of Poland.

8. Sviatopolk I of Kiev (978 - 1019)

With an HPI of 70.74, Sviatopolk I of Kiev is the 8th most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 35 different languages.

Sviatopolk I Vladimirovich (also called Sviatopolk the Accursed or the Accursed Prince; Old East Slavic: Свѧтоплъкъ, romanized: Svętoplŭkŭ; c. 980 – 1019) was Prince of Turov from 988 to 1015 and Grand Prince of Kiev from 1015 to 1019. He earned his sobriquet after allegedly murdering his brothers during his bid to take the throne. His actual responsibility is disputed by historians. The Svyatopolk-Mirsky family of Rurikid origin attribute their descent from Sviatopolk. Tsar Peter the Great recognized their descent during his reign.

9. Zalman Shazar (1889 - 1974)

With an HPI of 69.42, Zalman Shazar is the 9th most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 38 different languages.

Zalman Shazar (Hebrew: זלמן שזר; November 24, 1889 – October 5, 1974) was a Russian-born Israeli politician, author and poet. Shazar served as the president of Israel for two terms, from 1963 to 1973.

10. Isser Harel (1912 - 2003)

With an HPI of 68.59, Isser Harel is the 10th most famous Belarusian Politician. His biography has been translated into 28 different languages.

Isser Harel (Hebrew: איסר הראל; 1912 – 18 February 2003) was spymaster of the intelligence and the security services of Israel and the Director of the Mossad (1952–1963). In his capacity as Mossad director, he oversaw the capture and covert transportation to Israel of Holocaust organizer Adolf Eichmann. Harel was the only individual in the history of the State of Israel to hold a position that consolidated both internal and external intelligence responsibilities.

People

Pantheon has 67 people classified as Belarusian politicians born between 978 and 1990. Of these 67, 28 (41.79%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Belarusian politicians include Alexander Lukashenko, Ivonka Survilla, and Myechyslaw Hryb. The most famous deceased Belarusian politicians include Shimon Peres, Menachem Begin, and Felix Dzerzhinsky. As of April 2024, 6 new Belarusian politicians have been added to Pantheon including Alexander Turchin, Viktor Lukashenko, and Maryna Vasileuskaya.

Living Belarusian Politicians

Go to all RankingsAlexander Lukashenko

1954 - Present

HPI: 79.35

Ivonka Survilla

1936 - Present

HPI: 60.82

Myechyslaw Hryb

1938 - Present

HPI: 59.90

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

1982 - Present

HPI: 59.83

Anatoly Chubais

1955 - Present

HPI: 59.70

Mikhail Myasnikovich

1950 - Present

HPI: 59.32

Alaksandar Milinkievič

1947 - Present

HPI: 58.60

Roman Golovchenko

1973 - Present

HPI: 57.23

Sergey Ling

1937 - Present

HPI: 56.55

Mikhail Chigir

1948 - Present

HPI: 54.74

Vladimir Resin

1936 - Present

HPI: 53.76

Gennady Novitsky

1949 - Present

HPI: 53.07

Deceased Belarusian Politicians

Go to all RankingsShimon Peres

1923 - 2016

HPI: 80.51

Menachem Begin

1913 - 1992

HPI: 77.55

Felix Dzerzhinsky

1877 - 1926

HPI: 76.33

Chaim Weizmann

1874 - 1952

HPI: 75.25

Andrei Gromyko

1909 - 1989

HPI: 74.94

Stanisław August Poniatowski

1732 - 1798

HPI: 74.82

Sviatopolk I of Kiev

978 - 1019

HPI: 70.74

Zalman Shazar

1889 - 1974

HPI: 69.42

Isser Harel

1912 - 2003

HPI: 68.59

Stanislav Shushkevich

1934 - 2022

HPI: 68.00

Mstislav I of Kiev

1076 - 1132

HPI: 67.49

Maria Kaczyńska

1942 - 2010

HPI: 66.88

Newly Added Belarusian Politicians (2025)

Go to all RankingsAlexander Turchin

1975 - Present

HPI: 50.26

Viktor Lukashenko

1975 - Present

HPI: 47.89

Maryna Vasileuskaya

1990 - Present

HPI: 36.93

Sviatlana Usovich

1980 - Present

HPI: 34.67

Alina Tumilovich

1990 - Present

HPI: 33.80

Vladimir Denisov

1984 - Present

HPI: 33.40

Overlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.