The Most Famous

INVENTORS from Germany

This page contains a list of the greatest German Inventors. The pantheon dataset contains 426 Inventors, 46 of which were born in Germany. This makes Germany the birth place of the 3rd most number of Inventors behind United States, and United Kingdom.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary German Inventors of all time. This list of famous German Inventors is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of German Inventors.

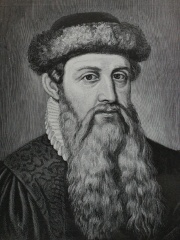

1. Johannes Gutenberg (1394 - 1468)

With an HPI of 90.58, Johannes Gutenberg is the most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 160 different languages on wikipedia.

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (c. 1393 – 1406 – 3 February 1468) was a German inventor and craftsman who invented the movable-type printing press. Though movable type was already in use in East Asia, Gutenberg's invention of the printing press enabled a much faster rate of printing. The printing press later spread across the world, and led to an information revolution and the unprecedented mass-spread of literature throughout Europe. It had a profound impact on the development of the Renaissance, Reformation, and humanist movements. Gutenberg's many contributions to printing include the invention of a process for mass-producing movable type; the use of oil-based ink for printing books; adjustable molds; mechanical movable type; and the invention of a wooden printing press similar to the agricultural screw presses of the period. Gutenberg's method for making type is traditionally considered to have included a type metal alloy and a hand mould for casting type. The alloy was a mixture of lead, tin, and antimony that melted at a relatively low temperature for faster and more economical casting, cast well, and created a durable type. His major work, the Gutenberg Bible, was the first printed version of the Bible and has been acclaimed for its high aesthetic and technical quality. Gutenberg is often cited as among the most influential figures in human history and has been commemorated around the world. To celebrate the 500th anniversary of his birth, the Gutenberg Museum was founded in his hometown of Mainz in 1900. In 1997, Time Life picked Gutenberg's invention as the most important of the second millennium.

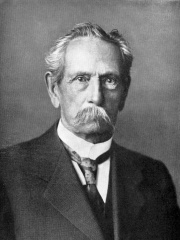

2. Karl Benz (1844 - 1929)

With an HPI of 88.12, Karl Benz is the 2nd most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 110 different languages.

Carl (or Karl) Friedrich Benz (German: [kaʁl ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈbɛnts] ; born Karl Friedrich Michael Vaillant; 25 November 1844 – 4 April 1929) was a German engine designer and automotive engineer. His Benz Patent-Motorwagen from 1885 is considered the first practical, modern automobile and the first car to be put into series production. He received a patent for the motorcar in 1886, the same year he first publicly drove the Benz Patent-Motorwagen. His company Benz & Cie., based in Mannheim, was the world's first automobile plant and largest of its day. In 1926, it merged with Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft to form Daimler-Benz, which produces the Mercedes-Benz among other brands. For his achievements, Benz is widely regarded as "the father of the car", and as the "father of the automobile industry".

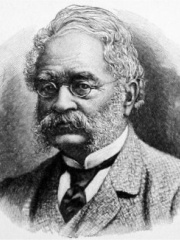

3. Nikolaus Otto (1832 - 1891)

With an HPI of 79.93, Nikolaus Otto is the 3rd most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 62 different languages.

Nicolaus August Otto (German pronunciation: [ˈnɪkolaʊ̯s ˈaʊ̯ɡʊst ˈɔto]; 10 June 1832 – 26 January 1891) was a German engineer who successfully developed the compressed charge internal combustion engine which ran on petroleum gas and led to the modern internal combustion engine. The Association of German Engineers (VDI) created DIN standard 1940 which says "Otto Engine: internal combustion engine in which the ignition of the compressed fuel-air mixture is initiated by a timed spark", which has been applied to all engines of this type since.

4. Karl Ferdinand Braun (1850 - 1918)

With an HPI of 77.57, Karl Ferdinand Braun is the 4th most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 93 different languages.

Karl Ferdinand Braun (German: [ˈfɛʁdinant ˈbʁaʊ̯n] ; 6 June 1850 – 20 April 1918) was a German applied physicist who shared the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics with Guglielmo Marconi for their contributions to the development of radio. With his two circuit system, long range radio transmissions and modern telecommunications were made possible. His invention of the phased array antenna in 1905 led to the development of radar, smart antennas, and MIMO. He built the first cathode-ray tube in 1897, which led to the development of television, and the first semiconductor diode in 1874, which co-started the development of electronics and electronic engineering. Braun was a co-founder of Telefunken, one of the pioneering communications and television companies. He has been called the "father of television" (shared with inventors like Paul Nipkow), the "great-grandfather of every semiconductor ever manufactured", and a co-father of radiotelegraphy, together with Marconi, laying the foundation for all modern wireless systems.

5. Hans Lippershey (1570 - 1619)

With an HPI of 76.77, Hans Lippershey is the 5th most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 42 different languages.

Hans Lipperhey (c. 1570 – buried 29 September 1619), also known as Johann Lippershey or simply Lippershey, was a German-Dutch spectacle-maker. He is commonly associated with the invention of the telescope, because he was the first one who tried to obtain a patent for it. It is, however, unclear if he was the first one to build a telescope.

6. Werner von Siemens (1816 - 1892)

With an HPI of 75.84, Werner von Siemens is the 6th most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 60 different languages.

Ernst Werner Siemens (von Siemens from 1888; SEEM-ənz; German: [ˈziːməns, -mɛns]; 13 December 1816 – 6 December 1892) was a German electrical engineer, inventor and industrialist. Siemens's name has been adopted as the SI unit of electrical conductance, the siemens. He founded the electrical and telecommunications conglomerate Siemens and invented the electric tram, trolley bus, electric locomotive and electric elevator. His dynamo laid the foundation for the modern age of electricity and he was involved in the development of the electric car.

7. Wilhelm Maybach (1846 - 1929)

With an HPI of 73.59, Wilhelm Maybach is the 7th most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 40 different languages.

Wilhelm Maybach (German: [ˈvɪlhɛlm ˈmaɪbax] ; 9 February 1846 – 29 December 1929) was an early German engine designer and industrialist. During the 1890s he was hailed in France, then the world centre for car production, as the "King of Designers". From the late 19th century Wilhelm Maybach, together with Gottlieb Daimler, developed light, high-speed internal combustion engines suitable for land, water, and air use. These were fitted to the world's first motorcycle, motorboat, and after Daimler's death, a new automobile introduced in late 1902, the Mercedes model, built to the specifications of Emil Jellinek. Maybach rose to become technical director of the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft (DMG) but did not get along with its chairmen. As a result, Maybach left DMG in 1907 to found Maybach-Motorenbau GmbH together with his son Karl in 1909; they manufactured Zeppelin engines. After the signing of the Versailles Treaty in 1919 the company started producing large luxury vehicles, branded as "Maybach". He died in 1929 and was succeeded by his son Karl Maybach. From around 1936 Maybach-Motorenbau designed and made almost all the engines fitted in German tanks and half-tracks used during World War 2, including those for the Panther, Tiger I and Tiger II heavy tanks. Continuing after the war, Maybach Motorenbau remained a subsidiary of Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, making diesel engines. During the 1960s Maybach came under the control of Daimler-Benz and was renamed MTU Friedrichshafen. In 2002 the Maybach brand name was revived for a luxury make but it was not successful. On 25 November 2011 Daimler-Benz announced they would cease producing automobiles under the Maybach brand name in 2013. In 2014, Daimler announced production of an ultra-luxury edition of the Mercedes-Benz S-Class under the new Mercedes-Maybach brand.

8. Karl Drais (1785 - 1851)

With an HPI of 73.02, Karl Drais is the 8th most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 46 different languages.

Karl Freiherr von Drais (full name: Karl Friedrich Christian Ludwig Freiherr Drais von Sauerbronn; 29 April 1785 – 10 December 1851) was a noble German forest official and significant inventor in the Biedermeier period. He is regarded as "the father" and as the inventor of the bicycle.

9. Konrad Zuse (1910 - 1995)

With an HPI of 72.62, Konrad Zuse is the 9th most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 60 different languages.

Konrad Ernst Otto Zuse (; German: [ˈkɔnʁaːt ˈtsuːzə]; 22 June 1910 – 18 December 1995) was a German civil engineer, pioneering computer scientist, inventor and businessman. His greatest achievement was the world's first programmable computer; the functional program-controlled Turing-complete Z3 became operational in May 1941. Thanks to this machine and its predecessors, Zuse is regarded by some as the inventor and father of the modern computer. Zuse was noted for the S2 computing machine, considered the first process control computer. In 1941, he founded one of the earliest computer businesses, producing the Z4, which became the world's first commercial computer. From 1943 to 1945 he designed Plankalkül, the first high-level programming language. In 1969, Zuse suggested the concept of a computation-based universe in his book Rechnender Raum (Calculating Space). Much of his early work was financed by his family and commerce, but after 1939 he was given resources by the government of Nazi Germany. Due to World War II, Zuse's work went largely unnoticed in the United Kingdom and United States. Possibly his first documented influence on a US company was IBM's option on his patents in 1946. The Z4 also served as the inspiration for the construction of the ERMETH, the first Swiss computer and one of the first in Europe.

10. Adam Opel (1837 - 1895)

With an HPI of 71.80, Adam Opel is the 10th most famous German Inventor. His biography has been translated into 38 different languages.

Adam Opel (9 May 1837 – 8 September 1895) was a German entrepreneur who founded the company Adam Opel AG, then a manufacturer of bicycles and sewing machines.

People

Pantheon has 46 people classified as German inventors born between 1394 and 1964. Of these 46, 3 (6.52%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living German inventors include Didi Senft, Andy Bechtolsheim, and Curt O. Schaller. The most famous deceased German inventors include Johannes Gutenberg, Karl Benz, and Nikolaus Otto. As of April 2024, 1 new German inventors have been added to Pantheon including Curt O. Schaller.

Living German Inventors

Go to all RankingsDidi Senft

1952 - Present

HPI: 56.63

Andy Bechtolsheim

1955 - Present

HPI: 54.56

Curt O. Schaller

1964 - Present

HPI: 45.69

Deceased German Inventors

Go to all RankingsJohannes Gutenberg

1394 - 1468

HPI: 90.58

Karl Benz

1844 - 1929

HPI: 88.12

Nikolaus Otto

1832 - 1891

HPI: 79.93

Karl Ferdinand Braun

1850 - 1918

HPI: 77.57

Hans Lippershey

1570 - 1619

HPI: 76.77

Werner von Siemens

1816 - 1892

HPI: 75.84

Wilhelm Maybach

1846 - 1929

HPI: 73.59

Karl Drais

1785 - 1851

HPI: 73.02

Konrad Zuse

1910 - 1995

HPI: 72.62

Adam Opel

1837 - 1895

HPI: 71.80

Emile Berliner

1851 - 1929

HPI: 71.45

Joseph Pilates

1883 - 1967

HPI: 68.58

Newly Added German Inventors (2025)

Go to all RankingsOverlapping Lives

Which Inventors were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Inventors since 1700.