The Most Famous

CYCLISTS from France

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary French Cyclists of all time. This list of famous French Cyclists is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of French Cyclists.

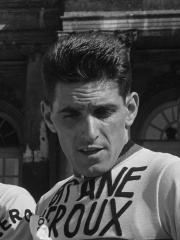

1. Jacques Anquetil (1934 - 1987)

With an HPI of 71.78, Jacques Anquetil is the most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 51 different languages on wikipedia.

Jacques Anquetil (pronounced [ʒak ɑ̃k.til]; 8 January 1934 – 18 November 1987) was a French road racing cyclist and the first cyclist to win the Tour de France five times, in 1957 and from 1961 to 1964. He stated before the 1961 Tour that he would gain the yellow jersey on day one and wear it all through the tour, a tall order with two previous winners in the field—Charly Gaul and Federico Bahamontes—but he did it. His victories in stage races such as the Tour were built on an exceptional ability to ride alone against the clock in individual time trial stages, which lent him the name "Monsieur Chrono". He won eight Grand Tours in his career, which was a record when he retired and was surpassed only by Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault.

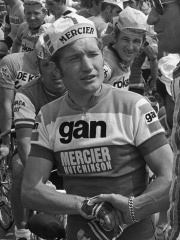

2. Raymond Poulidor (1936 - 2019)

With an HPI of 67.29, Raymond Poulidor is the 2nd most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 31 different languages.

Raymond Poulidor (French pronunciation: [ʁɛmɔ̃ pulidɔʁ]; 15 April 1936 – 13 November 2019), nicknamed "Pou-Pou" (pronounced [pu pu]), was a French professional racing cyclist, who rode for Mercier his entire career. His distinguished career coincided with two other outstanding riders – Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Merckx. This underdog position may have been the reason Poulidor was a favourite of the public. He was known as "The Eternal Second", because he never won the Tour de France despite finishing in second place three times, and in third place five times (including his final Tour at the age of 40). Despite his consistency, he never wore the yellow jersey as leader of the general classification in 14 Tours (of which he completed 12). He did win one Grand Tour, the 1964 Vuelta a España. Of the eighteen Grand Tours that he entered in his career, he finished in the top 10 fifteen times.

3. Bernard Hinault (b. 1954)

With an HPI of 66.54, Bernard Hinault is the 3rd most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 44 different languages.

Bernard Hinault (pronounced [bɛʁ.naʁ i.no]; born 14 November 1954) is a French former professional road cyclist. With 147 professional victories, including five times the Tour de France, he is often named among the greatest cyclists of all time. In his career, Hinault entered a total of thirteen Grand Tours. He abandoned one of them while in the lead, finished in 2nd place on two occasions and won the other ten, putting him one behind Merckx for the all-time record. No rider since Hinault has achieved more than seven. Hinault started cycling as an amateur in his native Brittany. After a successful amateur career, he signed with the Gitane–Campagnolo team to turn professional in 1975. He took breakthrough victories at both the Liège–Bastogne–Liège classic and the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré stage race in 1977. In 1978, he won his first two Grand Tours: the Vuelta a España and the Tour de France. In the following years, he was the most successful professional cyclist, adding another Tour victory in 1979 and a win at the 1980 Giro d'Italia. Although a knee injury forced him to quit the 1980 Tour de France while in the lead, he returned to win the World Championship road race later in the year. He added another Tour victory in 1981, before completing his first Giro-Tour double in 1982. After winning the 1983 Vuelta a España, a return of his knee problems forced him to miss that year's Tour de France, won by his teammate Laurent Fignon. Conflict within the Renault team led to his leaving and joining La Vie Claire. With his new team, he raced the 1984 Tour de France, but lost to Fignon by over ten minutes. He recovered the following year, winning another Giro-Tour double with the help of teammate Greg LeMond. In the 1986 Tour de France, he engaged in an intra-team rivalry with LeMond, who won his first of three Tours. Hinault retired at the end of the season. As of 2025 he is the most recent French winner of the men’s Tour de France. After his cycling career, Hinault turned to farming, while fulfilling enforcement duties for the organisers of the Tour de France until 2016. All through his career, Hinault was known by the nickname Le Blaireau ("The Badger"); he associated himself with the animal due to its aggressive nature, a trait he embodied on the bike. Within the peloton, Hinault assumed the role of patron, exercising authority over races he took part in.

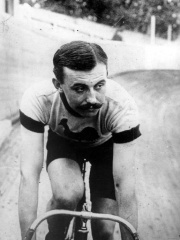

4. Lucien Petit-Breton (1882 - 1917)

With an HPI of 65.65, Lucien Petit-Breton is the 4th most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 34 different languages.

Lucien Georges Mazan (18 October 1882 – 20 December 1917), known by the pseudonym Lucien Petit-Breton (French pronunciation: [lysjɛ̃ p(ə)ti bʁətɔ̃]), was a French racing cyclist best known as the first two-time winner of the Tour de France. He was born in Plessé, Loire-Atlantique, a part of Brittany, now part of Pays de la Loire. When he was six he moved with his parents to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he took the nationality. His cycling career started when he won a bike in a lottery at the age of sixteen. As his father wanted him to do a 'real' job, he adapted the nickname Lucien Breton for races, to deceive his father. Later he changed it to Petit-Breton, because there already was another cyclist called Lucien Breton.

5. Henri Cornet (1884 - 1941)

With an HPI of 64.94, Henri Cornet is the 5th most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 30 different languages.

Henri Cornet (born Henri Jardry; 4 August 1884 – 18 March 1941) was a French cyclist who won the 1904 Tour de France. He is its youngest winner, just short of his 20th birthday.

6. François Faber (1887 - 1915)

With an HPI of 64.13, François Faber is the 6th most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 27 different languages.

François Faber (pronounced [fʁɑ̃.swa fa.bɛʁ]; 26 January 1887 – 9 May 1915) was a Luxembourgish racing cyclist. He was born in France. He was the first foreigner to win the Tour de France in 1909, and his record of winning 5 consecutive stages still stands. He died in World War I while fighting for France. Faber was known for his long solos; he is the only rider in Tour de France history to lead solo more than 1000 km.

7. Louis Trousselier (1881 - 1939)

With an HPI of 63.66, Louis Trousselier is the 7th most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 29 different languages.

Louis Trousselier (French pronunciation: [lwi tʁu.sɛlje]; 1881 – 24 April 1939) was a French racing cyclist who won the 1905 Tour de France. His other major wins were Paris–Roubaix, also in 1905, and the 1908 Bordeaux–Paris. He came third in the 1906 Tour de France and won 13 stages of the Tour de France over his career. He also competed in the men's 25 kilometres event at the 1900 Summer Olympics and won a bronze medal in the Men's points race.

8. René Pottier (1879 - 1907)

With an HPI of 63.19, René Pottier is the 8th most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 28 different languages.

René Pottier (5 June 1879 – 25 January 1907) was a French racing cyclist. Pottier won the amateur category of the 1903 Bordeaux–Paris race before turning professional. He came second in Paris–Roubaix 1905 and Bordeaux–Paris 1905, then third in 1906's Paris–Roubaix, before winning the Tour de France in 1906. He was considered the finest climber of the Tour. In the 1905 race he was first up the Ballon d'Alsace but lost the lead to Hippolyte Aucouturier after nails punctured his final spare tyre. He finished the stage only when Aucouturier gave him one of his spare tyres. Injury due to a fall on the next stage to Grenoble caused him to abandon. The following year he took five stage wins out of thirteen and overall victory with 31 points. Again he was first up the Ballon d'Alsace but this time he stayed ahead, finishing at Dijon 48 minutes before his nearest competitor. He also won in Grenoble by fifteen minutes and at Nice by 26 minutes. He completed the 4,546 km in 189 hours, 34 minutes at an average 23.98kmh. In September 1906 he won the Bol d'Or 24-hour cycle race at the Vélodrome Buffalo in Paris with 925.290 km. On 25 January 1907 he committed suicide by hanging himself on his bike hook after hearing his wife had found a lover while he was away at the Tour. A few weeks later, Henri Desgrange, patron of the Tour, erected a stele in his memory at the top of the Ballon d'Alsace, a summit in Vosges.

9. Octave Lapize (1887 - 1917)

With an HPI of 63.00, Octave Lapize is the 9th most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 28 different languages.

Octave Lapize (pronounced [ɔktav lapiz]; 24 October 1887 – 14 July 1917) was a French professional road racing cyclist and track cyclist. Most famous for winning the 1910 Tour de France and a bronze medal at the 1908 Summer Olympics in the men's 100 kilometres, he was a three-time winner of one-day classics, Paris–Roubaix and Paris–Brussels.

10. Laurent Fignon (1960 - 2010)

With an HPI of 62.35, Laurent Fignon is the 10th most famous French Cyclist. His biography has been translated into 39 different languages.

Laurent Patrick Fignon (French pronunciation: [loʁɑ̃ fiɲɔ̃]; 12 August 1960 – 31 August 2010) was a French professional road bicycle racer who won the Tour de France in 1983 and 1984, as well as the Giro d'Italia in 1989. He held the title of FICP World No. 1 in 1989. Fignon came close to winning the Tour de France for a third time in 1989 but was defeated by Greg LeMond by eight seconds, the closest margin ever to decide the Tour. Fignon won many classic races, including consecutive victories in Milan–San Remo in 1988 and 1989. He died from cancer in 2010.

People

Pantheon has 256 people classified as French cyclists born between 1876 and 2003. Of these 256, 208 (81.25%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living French cyclists include Bernard Hinault, Bernard Thévenet, and Lucien Aimar. The most famous deceased French cyclists include Jacques Anquetil, Raymond Poulidor, and Lucien Petit-Breton. As of April 2024, 40 new French cyclists have been added to Pantheon including Jean-Louis Harel, Jean-Michel Monin, and Gilles Delion.

Living French Cyclists

Go to all RankingsBernard Hinault

1954 - Present

HPI: 66.54

Bernard Thévenet

1948 - Present

HPI: 59.90

Lucien Aimar

1941 - Present

HPI: 59.22

André Darrigade

1929 - Present

HPI: 57.40

Jeannie Longo

1958 - Present

HPI: 57.09

Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle

1954 - Present

HPI: 56.16

Cyrille Guimard

1947 - Present

HPI: 54.91

Laurent Jalabert

1968 - Present

HPI: 53.28

Michel Vermeulin

1934 - Present

HPI: 53.05

Jean Forestier

1930 - Present

HPI: 52.41

Raymond Martin

1949 - Present

HPI: 51.47

Jean-René Bernaudeau

1956 - Present

HPI: 50.26

Deceased French Cyclists

Go to all RankingsJacques Anquetil

1934 - 1987

HPI: 71.78

Raymond Poulidor

1936 - 2019

HPI: 67.29

Lucien Petit-Breton

1882 - 1917

HPI: 65.65

Henri Cornet

1884 - 1941

HPI: 64.94

François Faber

1887 - 1915

HPI: 64.13

Louis Trousselier

1881 - 1939

HPI: 63.66

René Pottier

1879 - 1907

HPI: 63.19

Octave Lapize

1887 - 1917

HPI: 63.00

Laurent Fignon

1960 - 2010

HPI: 62.35

Louison Bobet

1925 - 1983

HPI: 62.02

Henri Pélissier

1889 - 1935

HPI: 61.81

André Leducq

1904 - 1980

HPI: 61.81

Newly Added French Cyclists (2025)

Go to all RankingsJean-Louis Harel

1965 - Present

HPI: 45.69

Jean-Michel Monin

1967 - Present

HPI: 45.15

Gilles Delion

1966 - Present

HPI: 43.94

Philippe Ermenault

1969 - Present

HPI: 42.47

Stéphane Goubert

1970 - Present

HPI: 42.30

Kévin Vauquelin

2001 - Present

HPI: 41.79

Catherine Marsal

1971 - Present

HPI: 40.76

Laurent Roux

1972 - Present

HPI: 40.17

Lenny Martinez

2003 - Present

HPI: 39.94

Nicolas Jalabert

1973 - Present

HPI: 39.51

Jérôme Neuville

1975 - Present

HPI: 38.39

Clara Sanchez

1983 - Present

HPI: 38.10

Overlapping Lives

Which Cyclists were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Cyclists since 1700.