The Most Famous

COMIC ARTISTS from United States

This page contains a list of the greatest American Comic Artists. The pantheon dataset contains 226 Comic Artists, 69 of which were born in United States. This makes United States the birth place of the 2nd most number of Comic Artists.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary American Comic Artists of all time. This list of famous American Comic Artists is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of American Comic Artists.

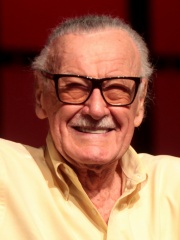

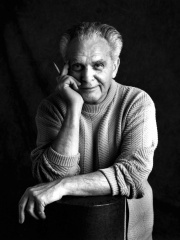

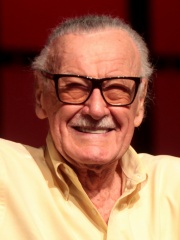

1. Stan Lee (1922 - 2018)

With an HPI of 78.26, Stan Lee is the most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 89 different languages on wikipedia.

Stan Lee (born Stanley Martin Lieber ; December 28, 1922 – November 12, 2018) was an American comic book writer, editor, publisher and producer. He rose through the ranks of a family-run business called Timely Comics which later became Marvel Comics. He was Marvel's primary creative leader for two decades, expanding it from a small publishing house division to a multimedia corporation that dominated the comics and film industries. In collaboration with others at Marvel – particularly co-plotters and artists Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko – he co-created iconic characters, including Spider-Man, the X-Men, Iron Man, Thor, the Hulk, Ant-Man, the Wasp, the Fantastic Four, Black Panther, Daredevil, Doctor Strange, the Scarlet Witch, and Black Widow. These and other characters' introductions in the 1960s pioneered a more naturalistic approach in superhero comics. In the 1970s, Lee challenged the restrictions of the Comics Code Authority, indirectly leading to changes in its policies. In the 1980s, he pursued the development of Marvel properties in other media, with mixed results. Following his retirement from Marvel in the 1990s, Lee remained a public figurehead for the company. He frequently made cameo appearances in films and television shows based on Marvel properties, on which he received an executive producer credit, which allowed him to become the actor with the highest-grossing film total ever. He continued independent creative ventures until his death, aged 95, in 2018. Lee was inducted into the comic book industry's Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 1994 and the Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1995. He received the NEA's National Medal of Arts in 2008.

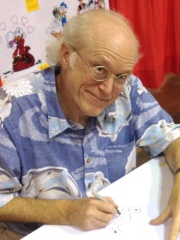

2. Charles M. Schulz (1922 - 2000)

With an HPI of 73.31, Charles M. Schulz is the 2nd most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 37 different languages.

Charles Monroe "Sparky" Schulz ( SHULZ; November 26, 1922 – February 12, 2000) was an American cartoonist who created the comic strip Peanuts, featuring the characters Charlie Brown and Snoopy. Schulz was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and developed an interest in drawing while growing up in Saint Paul. He was conscripted in 1943 and served in the United States Army during the final years of World War II. After returning to Minnesota, Schulz began his comic strip career with Li'l Folks in 1947. In 1950, Schulz redeveloped Li'l Folks as a four-panel comic strip and submitted it to United Features Syndicate, who renamed it Peanuts and began publishing that October. Schulz relocated to Northern California with his family in 1958. Beginning with A Charlie Brown Christmas in 1965, he helped write several animated television specials and four animated films based on his characters. He continued drawing Peanuts until his death in 2000. Schulz is regarded as one of the most influential cartoonists in history, influencing other cartoonists including Jim Davis, Murray Ball, Bill Watterson, Matt Groening and Dav Pilkey. He was inducted into the United States Hockey Hall of Fame in 1983 and the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1996, and was posthumously inducted into the United States Figure Skating Hall of Fame in 2007.

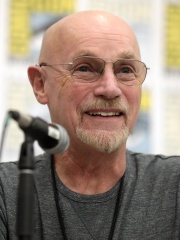

3. Frank Miller (b. 1957)

With an HPI of 70.15, Frank Miller is the 3rd most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 45 different languages.

Frank Miller (born January 27, 1957) is an American comic book creator, screenwriter, and director known for his comic book stories and graphic novels such as his run on Daredevil, for which he created the character Elektra, and subsequent Daredevil: Born Again, The Dark Knight Returns, Batman: Year One, Sin City, Ronin, and 300. Miller is noted for combining film noir and manga influences in his comic art creations. He said: "I realized when I started Sin City that I found American and English comics to be too wordy, too constipated, and Japanese comics to be too empty. So I was attempting to do a hybrid." Miller has received every major comic book industry award, and in 2015 he was inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame. Miller's feature film work includes writing the scripts for the 1990s science fiction films RoboCop 2 and RoboCop 3, sharing directing duties with Robert Rodriguez on Sin City and Sin City: A Dame to Kill For, producing the film 300, and directing the film adaptation of The Spirit. Sin City earned a Palme d'Or nomination.

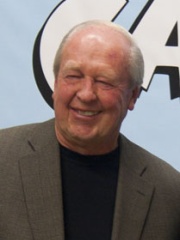

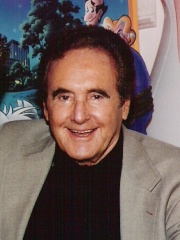

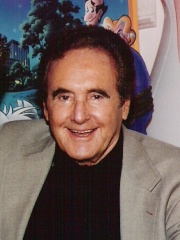

4. Joseph Barbera (1911 - 2006)

With an HPI of 70.11, Joseph Barbera is the 4th most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 51 different languages.

Joseph Roland Barbera ( bar-BAIR-ə; Italian: [barˈbɛːra]; March 24, 1911 – December 18, 2006) was an American animator and cartoonist. He co-founded the animation studio Hanna-Barbera alongside William Hanna. Born to Italian immigrants in New York City, Barbera hesitantly joined Van Beuren Studios in 1932 and subsequently Terrytoons in 1936. In 1937, he moved to California, and while working at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Barbera met Hanna. The two men began a collaboration that was at first best known for producing Tom and Jerry. In 1957, after MGM dissolved its animation department, they co-founded Hanna-Barbera, which became the most successful television animation studio in the business, producing programs such as The Flintstones, Yogi Bear, Scooby-Doo, Where Are You?, Top Cat, The Smurfs, Huckleberry Hound, and The Jetsons. In 1967, Hanna-Barbera was sold to Taft Broadcasting for $12 million, but Hanna and Barbera remained heads of the company. In 1991, the studio was sold to Turner Broadcasting System, which merged with Time Warner, owners of Warner Bros., in 1996; Hanna and Barbera stayed on as advisors. Hanna and Barbera directed seven Academy Award-winning films and won eight Emmy Awards. Their cartoon shows have become cultural icons, and their cartoon characters have appeared in other media, such as films, books, and toys. Hanna-Barbera's shows had a worldwide audience of over 300 million people in the 1960s and have been translated into more than 28 languages.

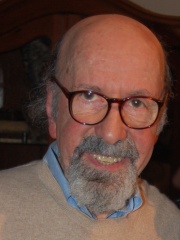

5. Carl Barks (1901 - 2000)

With an HPI of 70.02, Carl Barks is the 5th most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 44 different languages.

Carl Barks (March 27, 1901 – August 25, 2000) was an American cartoonist, author, and painter. He is best known for his work in Disney comic books, as the writer and artist of the first Donald Duck stories and as the creator of Scrooge McDuck. He worked anonymously until late in his career; fans dubbed him "The Duck Man" and "The Good Duck Artist". In 1987, Barks was one of the three inaugural inductees of the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame. Barks worked for the Disney Studio and Western Publishing where he created Duckburg and many of its inhabitants, such as Scrooge McDuck (1947), Gladstone Gander (1948), the Beagle Boys (1951), The Junior Woodchucks (1951), Gyro Gearloose (1952), Cornelius Coot (1952), Flintheart Glomgold (1956), John D. Rockerduck (1961) and Magica De Spell (1961). He has been named by animation historian Leonard Maltin as "the most popular and widely read artist-writer in the world". Will Eisner called him "the Hans Christian Andersen of comic books." Beginning especially in the 1980s, Barks' artistic contributions would be a primary source for animated adaptations such as DuckTales and its 2017 remake.

6. Jack Kirby (1917 - 1994)

With an HPI of 68.39, Jack Kirby is the 6th most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 56 different languages.

Jack Kirby (; born Jacob Kurtzberg; August 28, 1917 – February 6, 1994) was an American comic book artist, widely regarded as one of the medium's major innovators and one of its most prolific and influential creators. He grew up in New York City and learned to draw cartoon figures by tracing characters from comic strips and editorial cartoons. He entered the nascent comics industry in the 1930s, drawing various comics features under different pen names, including Jack Curtiss, before settling on Jack Kirby. In 1940, he and writer-editor Joe Simon created the highly successful superhero character Captain America for Timely Comics, predecessor of Marvel Comics. During the 1940s, Kirby regularly teamed with Simon, creating numerous characters for that company and for National Comics Publications, later to become DC Comics. After serving in the European Theater in World War II, Kirby produced work for DC Comics, Harvey Comics, Hillman Periodicals and other publishers. At Crestwood Publications, he and Simon created the genre of romance comics and later founded their own short-lived comic company, Mainline Publications. Kirby was involved in Timely's 1950s iteration, Atlas Comics, which in the next decade became Marvel. There, in the 1960s, Kirby co-created many of the company's major characters, including Ant-Man, the Avengers, the Black Panther, the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, Iron Man, the Silver Surfer, Thor, and the X-Men, among many others. Kirby's titles garnered high sales and critical acclaim, but in 1970, feeling he had been treated unfairly, largely in the realm of authorship credit and creators' rights, Kirby left the company for rival DC. At DC, Kirby created his Fourth World saga which spanned several comics titles. While these series proved commercially unsuccessful and were canceled, the Fourth World's New Gods have continued as a significant part of the DC Universe. Kirby returned to Marvel briefly in the mid-to-late 1970s, then ventured into television animation and independent comics. In his later years, Kirby, who has been called "the William Blake of comics", began receiving great recognition in the mainstream press for his career accomplishments, and in 1987 he was one of the three inaugural inductees of the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame. In 2017, Kirby was posthumously named a Disney Legend for his creations not only in the field of publishing, but also because those creations formed the basis for The Walt Disney Company's financially and critically successful media franchise, the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Kirby was married to Rosalind Goldstein in 1942. They had four children and remained married until his death from heart failure in 1994, at the age of 76. The Jack Kirby Awards and Jack Kirby Hall of Fame were named in his honor, and he is known as "The King" among comics fans for his many influential contributions to the medium.

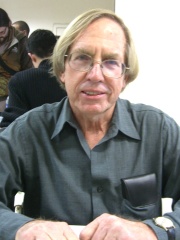

7. Matt Groening (b. 1954)

With an HPI of 68.13, Matt Groening is the 7th most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 64 different languages.

Matthew Abram Groening ( GRAY-ning; born February 15, 1954) is an American cartoonist and animator. He is the creator of the television series The Simpsons (1989–present), Futurama (1999–2003, 2008–2013, 2023–present), and Disenchantment (2018–2023), and the comic strip Life in Hell (1977–2012). Born in Portland, Oregon, Groening made his first professional cartoon sale of Life in Hell to the avant-garde magazine Wet in 1978. At its peak, it was carried in 250 weekly newspapers and caught the attention of the producer James L. Brooks, who contacted Groening in 1985 about adapting it for animated sequences for the Fox variety show The Tracey Ullman Show. Fearing the loss of ownership rights, Groening created a new set of characters, the Simpson family. The shorts were spun off into their own series, The Simpsons, which became the longest-running American primetime television series and the longest-running American animated series and sitcom. In 1997, Groening and former Simpsons writer David X. Cohen developed Futurama, an animated series about life in the year 3000, which premiered in 1999. It ran for four years on Fox, was picked up in 2008 by Comedy Central for another 5 years, and was picked up again by Hulu in 2023. In 2016, Groening developed a series for Netflix, Disenchantment, which premiered in August 2018. Groening has won 14 Primetime Emmy Awards, 12 for The Simpsons and 2 for Futurama, and a British Comedy Award for "outstanding contribution to comedy" in 2004. In 2002, he won the National Cartoonist Society Reuben Award for his work on Life in Hell. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on February 14, 2012.

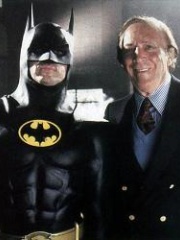

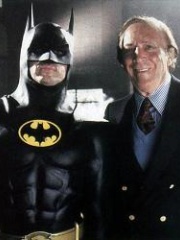

8. Bob Kane (1915 - 1998)

With an HPI of 67.12, Bob Kane is the 8th most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 43 different languages.

Robert Kane (né Kahn ; October 24, 1915 – November 3, 1998) was an American comic book writer, animator, and artist who co-created Batman (with Bill Finger) and many other early related characters for DC Comics. He was inducted into the comic book industry's Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1993 and into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 1996.

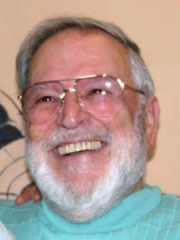

9. Joe Simon (1913 - 2011)

With an HPI of 66.39, Joe Simon is the 9th most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 25 different languages.

Joseph Henry Simon (born Hymie Simon; October 11, 1913 – December 14, 2011) was an American comic book writer, artist, editor, and publisher. Simon created or co-created many important characters in the 1930s–1940s Golden Age of Comic Books and served as the first editor of Timely Comics, the company that would evolve into Marvel Comics. With his partner, artist Jack Kirby, he co-created Captain America, one of comics' most enduring superheroes, and the team worked extensively on such features at DC Comics as the 1940s Sandman and Sandy the Golden Boy, and co-created the Newsboy Legion, the Boy Commandos, and Manhunter. Simon and Kirby creations for other comics publishers include Boys' Ranch, Fighting American and the Fly. In the late 1940s, the duo created the field of romance comics, and were among the earliest pioneers of horror comics. Simon, who went on to work in advertising and commercial art, also founded the satirical magazine Sick in 1960, remaining with it for over a decade. He briefly published with DC Comics in the 1970s. Simon was inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 1999.

10. Steve Ditko (1927 - 2018)

With an HPI of 66.11, Steve Ditko is the 10th most famous American Comic Artist. His biography has been translated into 43 different languages.

Stephen John Ditko (; November 2, 1927 – c. June 29, 2018) was an American comic book artist best known for being the co-creator of Marvel superheroes Spider-Man and Doctor Strange. He also made notable contributions to the character of Iron Man, introducing the character's signature red and yellow design. Ditko studied under Batman artist Jerry Robinson at the Cartoonist and Illustrators School in New York City. He began his professional career in 1953, working in the studio of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, beginning as an inker and coming under the influence of artist Mort Meskin. During this time, he began his long association with Charlton Comics, where he did work in the genres of science fiction, horror, and mystery. He also co-created the superhero Captain Atom in 1960. During the 1950s, Ditko also drew for Atlas Comics, a forerunner of Marvel Comics. He went on to contribute much significant work to Marvel. Ditko was the artist for the first 38 issues of The Amazing Spider-Man, co-creating much of the Spider-Man supporting characters and villains with Stan Lee. Beginning with issue #25, Ditko was also credited as the plotter. In 1966, after being the exclusive artist on The Amazing Spider-Man and the "Doctor Strange" feature in Strange Tales, Ditko left Marvel. He continued to work for Charlton and also DC Comics, including a revamp of the long-running character the Blue Beetle and creating or co-creating The Question, The Creeper, Shade, the Changing Man, Nightshade, and Hawk and Dove. Ditko also began contributing to small independent publishers, where he created Mr. A, a hero reflecting the influence of Ayn Rand's philosophy of Objectivism. Ditko largely declined to give interviews, saying he preferred to communicate through his work. He responded to fan mail, sending thousands of handwritten letters during his lifetime. Ditko was inducted into the comics industry's Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1990 and into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 1994. In 2024, Ditko was named a Disney Legend for his contributions to Publishing.

People

Pantheon has 69 people classified as American comic artists born between 1863 and 1992. Of these 69, 35 (50.72%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living American comic artists include Frank Miller, Matt Groening, and Don Rosa. The most famous deceased American comic artists include Stan Lee, Charles M. Schulz, and Joseph Barbera. As of April 2024, 3 new American comic artists have been added to Pantheon including Steve Purcell, Alex Ross, and Rob Liefeld.

Living American Comic Artists

Go to all RankingsFrank Miller

1957 - Present

HPI: 70.15

Matt Groening

1954 - Present

HPI: 68.13

Don Rosa

1951 - Present

HPI: 64.36

Jim Davis

1945 - Present

HPI: 59.26

Robert Crumb

1943 - Present

HPI: 57.68

John Romita Jr.

1956 - Present

HPI: 57.18

Larry Lieber

1931 - Present

HPI: 55.23

Roy Thomas

1940 - Present

HPI: 54.02

Mike Mignola

1960 - Present

HPI: 51.55

Marv Wolfman

1946 - Present

HPI: 51.23

Jim Starlin

1949 - Present

HPI: 51.11

Alison Bechdel

1960 - Present

HPI: 50.92

Deceased American Comic Artists

Go to all RankingsStan Lee

1922 - 2018

HPI: 78.26

Charles M. Schulz

1922 - 2000

HPI: 73.31

Joseph Barbera

1911 - 2006

HPI: 70.11

Carl Barks

1901 - 2000

HPI: 70.02

Jack Kirby

1917 - 1994

HPI: 68.39

Bob Kane

1915 - 1998

HPI: 67.12

Joe Simon

1913 - 2011

HPI: 66.39

Steve Ditko

1927 - 2018

HPI: 66.11

John Romita Sr.

1930 - 2023

HPI: 64.38

Will Eisner

1917 - 2005

HPI: 64.11

Bill Finger

1914 - 1974

HPI: 62.89

Winsor McCay

1867 - 1934

HPI: 62.54

Newly Added American Comic Artists (2025)

Go to all RankingsSteve Purcell

1961 - Present

HPI: 44.99

Alex Ross

1970 - Present

HPI: 43.34

Rob Liefeld

1967 - Present

HPI: 40.55

Overlapping Lives

Which Comic Artists were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Comic Artists since 1700.