The Most Famous

SOCIAL ACTIVISTS from United Kingdom

This page contains a list of the greatest British Social Activists. The pantheon dataset contains 840 Social Activists, 56 of which were born in United Kingdom. This makes United Kingdom the birth place of the 3rd most number of Social Activists behind United States, and India.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary British Social Activists of all time. This list of famous British Social Activists is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of British Social Activists.

1. Nicholas Winton (1909 - 2015)

With an HPI of 79.12, Nicholas Winton is the most famous British Social Activist. His biography has been translated into 52 different languages on wikipedia.

Sir Nicholas George Winton (né Wertheim; 19 May 1909 – 1 July 2015) was a British stockbroker and humanitarian who helped to rescue refugee children, mostly Jewish, whose families had fled persecution by Nazi Germany. Born to German-Jewish parents who had immigrated to Britain at the beginning of the 20th century, Winton assisted in the rescue of 669 children from Czechoslovakia on the eve of World War II. On a brief visit to Czechoslovakia, he helped compile a list of children in danger and, returning to Britain, he worked to fulfill the legal requirements of bringing the children to Britain and finding homes and sponsors for them. This operation was later known as the Czech Kindertransport (German for 'children's transport'). His humanitarian accomplishments remained unknown and unnoticed by the world for nearly 50 years until 1988 when he was invited to the BBC television programme That's Life!, where he was reunited with dozens of the children he had helped come to Britain and was introduced to many of their children and grandchildren. The British press celebrated him and dubbed him the "British Schindler". In 2003, Winton was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for "services to humanity, in saving Jewish children from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia". In 2014, he was awarded the highest honour of the Czech Republic, the Order of the White Lion (1st class), by Czech President Miloš Zeman. Winton died in 2015, aged 106.

2. Betty Williams (1943 - 2020)

With an HPI of 78.16, Betty Williams is the 2nd most famous British Social Activist. Her biography has been translated into 70 different languages.

Elizabeth Williams (née Smyth; 22 May 1943 – 17 March 2020) was a peace activist from Northern Ireland. She was a co-recipient with Mairead Corrigan of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1976 for her work as a cofounder of Community of Peace People, an organisation dedicated to promoting a peaceful resolution to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Williams headed the Global Children's Foundation and was the President of the World Centre of Compassion for Children International. She was also the Chair of Institute for Asian Democracy in Washington D.C. She lectured widely on topics of peace, education, inter-cultural and inter-faith understanding, anti-extremism, and children's rights. Williams was a founding member of the Nobel Laureate Summit, which has taken place annually since 2000. In 2006, Williams became a founder of the Nobel Women's Initiative along with Nobel Peace Laureates Mairead Corrigan Maguire, Shirin Ebadi, Wangari Maathai, Jody Williams and Rigoberta Menchú Tum. These six women, representing North and South America, the Middle East, Europe and Africa, brought together their experiences in a united effort for peace with justice and equality. It is the goal of the Nobel Women's Initiative to help strengthen work being done in support of women's rights around the world. Williams was also a member of PeaceJam.

3. Guy Fawkes (1570 - 1606)

With an HPI of 77.05, Guy Fawkes is the 3rd most famous British Social Activist. His biography has been translated into 70 different languages.

Guy Fawkes (; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educated in York; his father died when Fawkes was eight years old, after which his mother married a recusant Catholic. Fawkes converted to Catholicism and left for mainland Europe, where he fought for Catholic Spain in the Eighty Years' War against Protestant Dutch reformers in the Low Countries. He travelled to Spain to seek support for a Catholic rebellion in England without success. He later met Thomas Wintour, with whom he returned to England. Wintour introduced him to Robert Catesby, who planned to assassinate King James I and restore a Catholic monarch to the throne. The plotters leased an undercroft beneath the House of Lords; Fawkes was placed in charge of the gunpowder that they stockpiled there. The authorities were prompted by an anonymous letter to search Westminster Palace during the early hours of 5 November, and they found Fawkes guarding the explosives. He was questioned and tortured over the next few days and confessed to wanting to blow up the House of Lords. Fawkes was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. However, at his execution on 31 January, he died when his neck was broken as he was hanged, with some sources claiming that he deliberately jumped to make this happen; he thus avoided the agony of his sentence. He became synonymous with the Gunpowder Plot, the failure of which has been commemorated in the UK as Guy Fawkes Night since 5 November 1605, when his effigy is traditionally burned on a bonfire, commonly accompanied by fireworks.

4. Robert Owen (1771 - 1858)

With an HPI of 76.71, Robert Owen is the 4th most famous British Social Activist. His biography has been translated into 66 different languages.

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist, political philosopher and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the co-operative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted experimental socialistic communities, sought a more collective approach to child-rearing, and 'believed in lifelong education, establishing an Institute for the Formation of Character and School for Children that focused less on job skills than on becoming a better person'. Having trained as a draper in Stamford, Lincolnshire Owen worked in London before relocating at age 18 to Manchester and textile manufacturing. He gained wealth in the early 1800s from a textile mill at New Lanark, Scotland. In 1824, he moved to America and put most of his fortune in an experimental socialistic community at New Harmony, Indiana, as a preliminary for his utopian society. It lasted about two years. Other Owenite communities also failed, and in 1828 Owen returned to London, where he continued to champion the working class, lead in developing co-operatives and the trade union movement, and support child labour legislation and free co-educational schools.

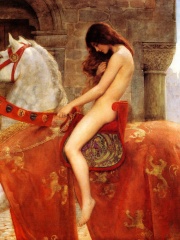

5. Lady Godiva (990 - 1067)

With an HPI of 74.54, Lady Godiva is the 5th most famous British Social Activist. Her biography has been translated into 57 different languages.

Lady Godiva (; died between 1066 and 1086), in Old English Godgifu, was a late Anglo-Saxon noblewoman who is relatively well documented as the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia, and a patron of various churches and monasteries. She is mainly remembered for a legend dating back to at least the 13th century, in which she rode naked – covered only by her long hair – through the streets of Coventry to gain a remission of the oppressive taxation that her husband, Leofric, imposed on his tenants. The name "Peeping Tom" for a voyeur originates from later versions of this legend, in which a man named Thomas watched her ride and was struck blind or dead.

6. Emmeline Pankhurst (1858 - 1928)

With an HPI of 73.94, Emmeline Pankhurst is the 6th most famous British Social Activist. Her biography has been translated into 68 different languages.

Emmeline Pankhurst (; née Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was a British political activist who organised the British suffragette movement and helped women to win in 1918 the right to vote in Great Britain and Ireland. In 1999, Time named her as one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century, stating that "she shaped an idea of objects for our time" and "shook society into a new pattern from which there could be no going back". She was widely criticised for her militant tactics, and historians disagree about their effectiveness, but her work is recognised as a crucial element in achieving women's suffrage in the United Kingdom. Born in the Moss Side district of Manchester to politically active parents, Pankhurst was 16 when she was introduced to the women's suffrage movement. She founded and became involved with the Women's Franchise League, which advocated suffrage for both married and unmarried women. When that organisation broke apart, she tried to join the left-leaning Independent Labour Party through her friendship with socialist Keir Hardie but was initially refused membership by the local branch on account of her sex. While working as a Poor Law Guardian, she was shocked at the harsh conditions she encountered in Manchester's workhouses. In 1903, Pankhurst founded the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), an all-women suffrage advocacy organisation dedicated to "deeds, not words". The group identified as independent from – and often in opposition to – political parties. It became known for physical confrontations: its members smashed windows and assaulted police officers. Pankhurst, her daughters, and other WSPU activists received repeated prison sentences, where they staged hunger strikes to secure better conditions, and were often force-fed. As Pankhurst's eldest daughter Christabel took leadership of the WSPU, antagonism between the group and the government grew. Eventually, the group adopted bombings and arson as a tactic, and more moderate organisations spoke out against the Pankhurst family. In 1913, several prominent individuals left the WSPU, among them Pankhurst's younger daughters, Adela and Sylvia. Emmeline was so furious that she "gave [Adela] a ticket, £20, and a letter of introduction to a suffragette in Australia, and firmly insisted that she emigrate". Adela complied and the family rift was never healed. Sylvia became a socialist. With the advent of the First World War, Emmeline and Christabel called an immediate halt to the militant terrorism in support of the British government's stand against the "German Peril". Emmeline organised and led a massive procession called the Women's Right to Serve demonstration to illustrate women's contribution to the war effort. Emmeline and Christabel urged women to aid industrial production and encouraged young men to fight. In 1918, the Representation of the People Act granted votes to all men over the age of 21 and women over the age of 30. This discrepancy was intended to ensure that men did not become minority voters as a consequence of the huge number of deaths suffered during the First World War. She transformed the WSPU machinery into the Women's Party, which was dedicated to promoting women's equality in public life. In her later years, she became concerned with what she perceived as the menace posed by Bolshevism and joined the Conservative Party. She was selected as the Conservative candidate for Whitechapel and St Georges in 1927. She died on 14 June 1928, only weeks before the Conservative government's Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 extended the vote to all women over 21 years of age on 2 July 1928. She was commemorated two years later with a statue in Victoria Tower Gardens, next to the Houses of Parliament.

7. Mairead Maguire (b. 1944)

With an HPI of 69.94, Mairead Maguire is the 7th most famous British Social Activist. Her biography has been translated into 69 different languages.

Mairead Maguire (born 27 January 1944), also known as Mairead Corrigan Maguire and formerly as Mairéad Corrigan, is a peace activist from Northern Ireland. She co-founded, with Betty Williams and Ciaran McKeown, the Women for Peace, which later became the Community for Peace People, an organization dedicated to encouraging a peaceful resolution of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Maguire and Williams were awarded the 1976 Nobel Peace Prize.

8. Thomas Cranmer (1489 - 1556)

With an HPI of 68.96, Thomas Cranmer is the 8th most famous British Social Activist. His biography has been translated into 56 different languages.

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a martyr in the Church of England. Cranmer helped build the case for the annulment of Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon, which was one of the causes of the separation of the English Church from union with the Holy See. Along with Thomas Cromwell, he supported the principle of royal supremacy, in which the king was considered sovereign over the Church within his realm and protector of his people from the abuses of Rome. During Cranmer's tenure as Archbishop of Canterbury, he established the first doctrinal and liturgical structures of the reformed Church of England. Under Henry's rule, Cranmer did not make many radical changes in the Church due to power struggles between religious conservatives and reformers. He published the first officially authorised vernacular (English) service, the Exhortation and Litany. When Edward, who was devout and had been raised in the tenets of a reformed Church, came to the throne, Cranmer was able to promote faster changes. He wrote and compiled the first two editions of the Book of Common Prayer, a complete liturgy for the English Church, turning to the language of the people. With the assistance of several Continental reformers to whom he gave refuge, he changed doctrine or discipline in areas such as the Eucharist, clerical celibacy, the role of images in places of worship, and the veneration of saints. Cranmer promulgated the new doctrines through the prayer book, the Homilies and other publications. After the accession of the Catholic Mary I, Cranmer was put on trial for treason and heresy. Imprisoned for over two years and under pressure from state and Church authorities, he made several recantations and reconciled himself with the Catholic Church. While this would have customarily absolved him from the heresy charge, Mary wanted him executed on the treason charge, and he was burned at the stake on 21 March 1556; on the day of his execution, he publicly withdrew his recantations, to die a heretic to Catholics and a martyr for the principles of the English Reformation. Cranmer's death was immortalised in Foxe's Book of Martyrs and his legacy lives on within the Church of England through the Book of Common Prayer and the Thirty-nine Articles, an Anglican statement of faith derived from his work.

9. Annie Besant (1847 - 1933)

With an HPI of 68.96, Annie Besant is the 9th most famous British Social Activist. Her biography has been translated into 55 different languages.

Annie Besant (; née Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights and Home Rule activist, educationist, and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an ardent supporter of both Irish and Indian self-rule. She became the first female president of the Indian National Congress in 1917. She became a prominent speaker for the National Secular Society (NSS), as well as a writer, and a close friend of Charles Bradlaugh. In 1877 they were prosecuted for publishing a book by birth control campaigner Charles Knowlton. Thereafter, she became involved with union actions, including the Bloody Sunday demonstration and the London matchgirls strike of 1888. She was a leading speaker for both the Fabian Society and the Marxist Social Democratic Federation (SDF). She was also elected to the London School Board for Tower Hamlets, topping the poll, even though few women were qualified to vote at that time. In 1890 Besant met Helena Blavatsky, and over the next few years her interest in theosophy grew, whilst her interest in secular matters waned. She became a member of the Theosophical Society and a prominent lecturer on the subject. As part of her theosophy-related work, she travelled to India. In 1898 she helped establish the Central Hindu School, and in 1922 she helped establish the Hyderabad (Sind) National Collegiate Board in Bombay (today's Mumbai), India. The Theosophical Society Auditorium in Hyderabad, Sindh (Sindh) is called Besant Hall in her honour. In 1902, she established the first overseas Lodge of the International Order of Co-Freemasonry, Le Droit Humain. Over the next few years, she established lodges in many parts of the British Empire. In 1907 she became president of the Theosophical Society, whose international headquarters were, by then, located in Adyar, Madras (Chennai). Besant also became involved in politics in India, joining the Indian National Congress. When World War I broke out in 1914, she helped launch the Home Rule League to campaign for democracy in India, and dominion status within the British Empire. This led to her election as president of the Indian National Congress, in late 1917. In the late 1920s, Besant travelled to the United States with her protégé and adopted son Jiddu Krishnamurti, who she claimed was the new Messiah and incarnation of Buddha. Krishnamurti rejected these claims in 1929. After the war, she continued to campaign for Indian independence and for the causes of theosophy, she died in 1933.

10. Max Mosley (1940 - 2021)

With an HPI of 66.12, Max Mosley is the 10th most famous British Social Activist. His biography has been translated into 31 different languages.

Max Rufus Mosley (13 April 1940 – 23 May 2021) was a British businessman, lawyer and racing driver. He served as president of the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA), the governing body for Formula One. A barrister and amateur racing driver, Mosley was a founder and co-owner of March Engineering, a racing car constructor and Formula One racing team. He dealt with legal and commercial matters for the company between 1969 and 1977 and became its representative at the Formula One Constructors' Association (FOCA), the body that represents Formula One constructors. Together with Bernie Ecclestone, Mosley represented FOCA at the FIA and in its dealings with race organisers. In 1978, he became the official legal adviser to FOCA. In this role, Mosley and Marco Piccinini negotiated the first version of the Concorde Agreement, which settled a long-standing dispute between FOCA and the Fédération Internationale du Sport Automobile (FISA), a commission of the FIA and the then governing body of Formula One. Mosley was elected president of FISA in 1991 and became president of the FIA, FISA's parent body, in 1993. Mosley identified his major achievement as FIA President as the promotion of the European New Car Assessment Programme (Euro NCAP or Encap). He also promoted increased safety and the use of green technologies in motor racing. In 2008, stories about his sex life appeared in the British press, along with allegations regarding Nazi connotations. Mosley successfully sued the newspaper that published the allegations and maintained his position as FIA president. He stood down at the end of his term in 2009 and was replaced by his preferred successor, Jean Todt. Mosley was the youngest son of Sir Oswald Mosley, former leader of the British Union of Fascists, and Diana Mitford. He was educated in France, Germany, and Britain before attending university at Christ Church, Oxford, where he graduated with a degree in physics. He then changed to law and was called to the bar in 1964. In his teens and early twenties, Mosley was involved with his father's post-war political party, the Union Movement (UM). He commented that the association of his surname with fascism stopped him from developing his interest in politics further, although he briefly worked for the Conservative Party in the early 1980s, and was a donor to the Labour Party from the New Labour era until 2018. Mosley was the subject of Michael Shevloff's 2020 biographical documentary Mosley. He died at the age of 81 on 23 May 2021. An inquest confirmed his death as suicide following a diagnosis of terminal cancer.

People

Pantheon has 56 people classified as British social activists born between 100 BC and 2008. Of these 56, 10 (17.86%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living British social activists include Mairead Maguire, Ingrid Newkirk, and Arthur Scargill. The most famous deceased British social activists include Nicholas Winton, Betty Williams, and Guy Fawkes. As of April 2024, 4 new British social activists have been added to Pantheon including Laura Lopes, Nadiya Hussain, and Kate Rusby.

Living British Social Activists

Go to all RankingsMairead Maguire

1944 - Present

HPI: 69.94

Ingrid Newkirk

1949 - Present

HPI: 50.95

Arthur Scargill

1938 - Present

HPI: 49.33

Anthony Dod Mantle

1955 - Present

HPI: 47.77

Laura Lopes

1978 - Present

HPI: 43.55

Anjem Choudary

1967 - Present

HPI: 41.24

Nadiya Hussain

1984 - Present

HPI: 32.75

Kate Rusby

1973 - Present

HPI: 32.59

Lilly Platt

2008 - Present

HPI: 26.51

Abby Gustaitis

1991 - Present

HPI: 5.17

Deceased British Social Activists

Go to all RankingsNicholas Winton

1909 - 2015

HPI: 79.12

Betty Williams

1943 - 2020

HPI: 78.16

Guy Fawkes

1570 - 1606

HPI: 77.05

Robert Owen

1771 - 1858

HPI: 76.71

Lady Godiva

990 - 1067

HPI: 74.54

Emmeline Pankhurst

1858 - 1928

HPI: 73.94

Thomas Cranmer

1489 - 1556

HPI: 68.96

Annie Besant

1847 - 1933

HPI: 68.96

Max Mosley

1940 - 2021

HPI: 66.12

Emily Davison

1872 - 1913

HPI: 64.55

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

1867 - 1954

HPI: 64.35

Christabel Pankhurst

1880 - 1958

HPI: 63.75

Newly Added British Social Activists (2025)

Go to all RankingsLaura Lopes

1978 - Present

HPI: 43.55

Nadiya Hussain

1984 - Present

HPI: 32.75

Kate Rusby

1973 - Present

HPI: 32.59

Anna Campbell

1991 - 2018

HPI: 29.91

Overlapping Lives

Which Social Activists were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 25 most globally memorable Social Activists since 1700.