The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Zimbabwe

This page contains a list of the greatest Zimbabwean Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 13 of which were born in Zimbabwe. This makes Zimbabwe the birth place of the 137th most number of Politicians behind Burundi, and Jamaica.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Zimbabwean Politicians of all time. This list of famous Zimbabwean Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Zimbabwean Politicians.

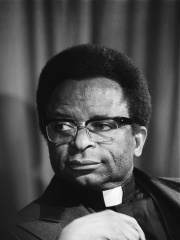

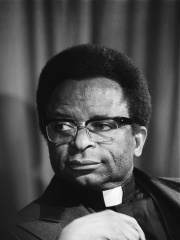

1. Albert Lutuli (1898 - 1967)

With an HPI of 77.77, Albert Lutuli is the most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 59 different languages on wikipedia.

Albert John Luthuli (c. 1898 – 21 July 1967) was a South African anti-apartheid activist, traditional leader, and politician who served as the President-General of the African National Congress from 1952 until his murder in 1967. Luthuli was born to a Zulu family in 1898 at a Seventh-day Adventist mission in Bulawayo, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In 1908 he moved to Groutville, where his parents and grandparents had lived, to attend school under the care of his uncle. After graduating from high school with a teaching degree, Luthuli became principal of a small school in Natal where he was the sole teacher. He accepted a government bursary to study for the Higher Teacher's Diploma at Adams College. After the completion of his studies in 1922, he accepted a teaching position at Adams College where he was one of the first African teachers. In 1928, he became the secretary of the Natal Native Teachers' Association, then its president in 1933. Luthuli's entered South African politics and the anti-apartheid movement in 1935, when he was elected chief of the Umvoti River Reserve in Groutville. As chief, he was exposed to the injustices facing many Africans due to the South African government's increasingly segregationist policies. This segregation would later evolve into apartheid, a form of institutionalized racial segregation, following the National Party's election victory in 1948. Luthuli joined the African National Congress (ANC) in 1944 and was elected the provincial president of the Natal branch in 1951. A year later in 1952, Luthuli led the Defiance Campaign to protest the pass laws and other laws of apartheid. As a result, the government removed him from his chief position as he refused to choose between being a member of the ANC or a chief at Groutville. In the same year, he was elected President-General of the ANC. After the Sharpeville massacre, where sixty-nine Africans were killed, leaders within the ANC such as Nelson Mandela believed the organisation should take up armed resistance against the government. Luthuli was initially against the use of violence. He later gradually came to accept it, but stayed committed to nonviolence on a personal level. Following four banning orders, the imprisonment and exile of his political allies, and the banning of the ANC, Luthuli's power as President-General gradually waned. The subsequent creation of uMkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC's paramilitary wing, marked the anti-apartheid movement's shift from nonviolence to an armed struggle. Inspired by his Christian faith and the nonviolent methods used by Gandhi, Luthuli was praised for his dedication to nonviolent resistance against apartheid as well as his vision of a non-racial South African society. In 1961, Luthuli was awarded the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in leading the nonviolent anti-apartheid movement. Luthuli's supporters brand him as a global icon of peace similar to Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr, the latter of whom was a follower and admirer of Luthuli. He formed multi-racial alliances with the South African Indian Congress and the white Congress of Democrats, frequently drawing a backlash from Africanists in the ANC. The Africanist bloc believed that Africans should not ally themselves with other races, since Africans were the most disadvantaged race under apartheid. This schism led to the creation of the Pan-Africanist Congress.

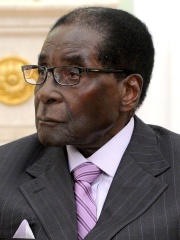

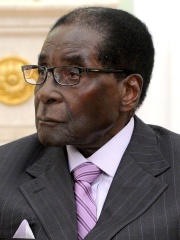

2. Robert Mugabe (1924 - 2019)

With an HPI of 76.85, Robert Mugabe is the 2nd most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 120 different languages.

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; Shona: [muɡaɓe]; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as the leader of Zimbabwe from 1980 until he was deposed in a coup in 2017. He served as the first Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from internationally recognised independence in 1980 to 1987, then as the second president of Zimbabwe from 1987 to 2017. He was also the Leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) from 1975 to 1980 and led its successor political party, the ZANU – Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF) as its First Secretary, from 1980 to 2017. Ideologically an African nationalist, during the 1970s and 1980s he identified as a Marxist–Leninist, and from the 1990s as a socialist. Mugabe was born to a poor Shona family in Kutama, then in Southern Rhodesia. Educated at Kutama College and the University of Fort Hare, he worked as a schoolteacher. Angered by white minority rule of his homeland within the British Empire, Mugabe embraced Marxism and joined African nationalists calling for an independent state controlled by the black majority. After making antigovernmental comments, he was convicted of sedition and imprisoned between 1964 and 1974. On release, he fled to Mozambique, established his leadership of ZANU, and oversaw its role in the Rhodesian Bush War, fighting Ian Smith's predominantly white government. He reluctantly participated in peace talks in the United Kingdom that resulted in the Lancaster House Agreement, putting an end to the war. In the 1980 general election, Mugabe led ZANU-PF to victory, becoming prime minister when the country, now renamed Zimbabwe, gained internationally recognised independence later that year. Mugabe's administration expanded healthcare and education and—despite his professed desire for a socialist society—adhered largely to mainstream economic policies. Mugabe's calls for racial reconciliation failed to stem growing white emigration, while relations with Joshua Nkomo's Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) also deteriorated. In the Gukurahundi of 1982–1987, Mugabe's 5th Brigade crushed ZAPU-linked opposition in Matabeleland in a campaign that killed at least 20,000 people. Internationally, he sent troops into the Second Congo War and chaired the Non-Aligned Movement (1986–1989), the Organisation of African Unity (1997–1998), and the African Union (2015–2016). Pursuing decolonisation, Mugabe emphasised the redistribution of land controlled by white farmers to landless blacks; from 2000 he encouraged black Zimbabweans to violently seize white-owned farms. Food production was severely impacted, leading to famine, hyperinflation, economic decline, and foreign sanctions. By 2007, Zimbabwe had the highest inflation rate in the world, at 7600%. Opposition to Mugabe grew, but he was re-elected in 2002, 2008, and 2013 through campaigns dominated by violence, electoral fraud, and nationalistic appeals to his rural Shona voter base. In 2017, members of his party ousted him in a coup, replacing him with former vice president Emmerson Mnangagwa. Having dominated Zimbabwe's politics for nearly four decades, Mugabe was a controversial figure. He was praised as a revolutionary hero of the African liberation struggle who helped free Zimbabwe from British colonialism, imperialism, and white minority rule. Critics accused Mugabe of being a dictator responsible for economic mismanagement and widespread corruption and human rights abuses, including anti-white racism, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

3. Emmerson Mnangagwa (b. 1942)

With an HPI of 69.85, Emmerson Mnangagwa is the 3rd most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 69 different languages.

Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa (US: mə-nəng-GAH-gwə, Shona: [m̩naˈᵑɡaɡwa]; born 15 September 1942) is a Zimbabwean politician who has served as the president of Zimbabwe since 2017. A member of ZANU–PF and a longtime ally of former president Robert Mugabe, he held a series of cabinet portfolios and he was Mugabe's first-vice president from 2014 until 2017, when he was dismissed before coming to power in a coup d'état. He secured his first full term as president in the disputed 2018 general election. Mnangagwa was re-elected in the 2023 Zimbabwean general election with 52.6% of the vote. Mnangagwa was born in 1942 in Shabani, Southern Rhodesia, to a large Shona family. His parents were farmers, and in the 1950s he and his family were forced to move to Northern Rhodesia because of his father's political activism. There he became active in anti-colonial politics, and in 1963 he joined the newly formed Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army, the militant wing of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). He returned to Rhodesia in 1964 as leader of the "Crocodile Gang", a group that attacked white-owned farms in the Eastern Highlands. In 1965, he bombed a train near Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) and was imprisoned for ten years, after which he was released and deported to the recently independent Zambia. He later studied law at the University of Zambia and practiced as an attorney for two years before going to Mozambique to rejoin ZANU. In Mozambique, he was assigned to be Robert Mugabe's assistant and bodyguard and accompanied him to the Lancaster House Agreement which resulted in Zimbabwe's recognised independence in 1980. After independence, Mnangagwa held a series of senior cabinet positions under Mugabe. From 1980 to 1988, he was the country's first minister of state security, and oversaw the Central Intelligence Organisation. His role in the Gukurahundi massacres, in which thousands of Ndebele civilians were killed during his tenure, is controversial. Mnangagwa was Minister of Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs from 1989 to 2000 and then Speaker of the Parliament from 2000 until 2005, when he was demoted to Minister of Rural Housing for openly jockeying to succeed the aging Mugabe. He returned to favour during the 2008 general election, in which he ran Mugabe's campaign, orchestrating political violence against the opposition Movement for Democratic Change – Tsvangirai. Mnangagwa served as Minister of Defence from 2009 until 2013, when he became justice minister again. He was also appointed First Vice-President in 2014 and was widely considered a leading candidate to succeed Mugabe. Mnangagwa's ascendancy was opposed by Mugabe's wife, Grace Mugabe, and her Generation 40 political faction. Mugabe dismissed Mnangagwa from his positions in November 2017, and he fled to South Africa. Soon after, General Constantino Chiwenga, backed by elements of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces and members of Mnangagwa's Lacoste political faction, launched a coup. After losing ZANU–PF's support, Mugabe resigned, and Mnangagwa returned to Zimbabwe to assume the presidency. Mnangagwa is commonly nicknamed "Garwe" or "Ngwena" (Shona: 'The crocodile'). It came initially from the name of the guerrilla group he founded, but later came to denote his political shrewdness. Reflecting this, the pro-Mnangagwa faction within ZANU–PF is named Lacoste after the French clothing company, known for its crocodile logo. He is also known in his home province of Midlands as "the Godfather". Mnangagwa was included in Time magazine's 100 Most Influential People of 2018.

4. Ian Smith (1919 - 2007)

With an HPI of 66.29, Ian Smith is the 4th most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 53 different languages.

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian and later Zimbabwean politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1979. He was the country's first leader to be born and raised in Rhodesia, and led the predominantly white government that unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom in November 1965 in opposition to their demands for the implementation of majority rule as a condition for independence. His 15 years in power were defined by the country's international isolation and involvement in the Rhodesian Bush War, which pitted the Rhodesian Security Forces against the Soviet and Chinese-funded military wings of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU). Smith was born to British settlers in the small town of Selukwe located in the Southern Rhodesian Midlands, four years before the colony became self-governing in 1923. During the Second World War, he served as a Royal Air Force fighter pilot, where a crash in Egypt resulted in facial and bodily wounds that remained conspicuous for the rest of his life. Following recovery, he served in Europe, where he was shot down and subsequently fought alongside Italian partisans. After the war, he established a farm in his hometown in 1948 and became a Member of Parliament for Selukwe that year. Originally a member of the Liberal Party, he defected to the United Federal Party in 1953, and served as Chief Whip from 1958 onwards. He left that party in 1961 in protest over the territory's new constitution, and went on to co-found the Rhodesian Front the following year. Smith became deputy prime minister following the Front's December 1962 election victory, and he stepped up to the premiership after Field resigned in April 1964, two months before the first events that led to the Bush War took place. After repeated talks with Britain broke down, Smith and his Cabinet unilaterally declared independence on 11 November 1965 to delay majority rule; shortly afterwards, the first phase of the war began in earnest. After further negotiations with the UK failed, Rhodesia cut all remaining British ties and reconstituted itself as a republic in 1970. Smith led the Front to four election victories over the course of his premiership; despite sporadic negotiations with moderate leader Abel Muzorewa over the course of the war, his support came exclusively from the white minority, with the black majority being widely disenfranchised under the country's electoral system. Following 15 years of protracted fighting, with economic sanctions, international pressure and a decline in South African support taking their toll, Smith conceded to the implementation of majority rule and signed the Internal Settlement in 1978 with moderate leaders, excluding ZANU and ZAPU. The new order failed to gain international recognition, and the war continued. After being succeeded as prime minister by Muzorawa, Smith took part in the trilateral peace negotiations at Lancaster House, which led to the free 1980 Southern Rhodesian general election and the recognition of an independent Zimbabwe. Following the election, Smith served as Leader of the Opposition for seven years and marked himself as a strident critic of Robert Mugabe's government. His criticisms persisted after his 1987 retirement: he dedicated much of his 1997 memoir, The Great Betrayal, to condemning Mugabe, UK politicians, and defending his premiership. In 2005, Smith moved to South Africa for medical treatment, where he died two years later at the age of 88. His ashes were subsequently repatriated and scattered at his farm. As Rhodesia's dominant political figure and public face in its final decades, Smith's reputation and legacy remains divisive. By his supporters, he has been hailed as "a political visionary ... who understood the uncomfortable truths of Africa", defending his rule as one of stability and a stalwart against communism. His critics, in turn, have condemned him as "an unrepentant racist ... who brought untold suffering to millions of Zimbabweans", as the leader of a white supremacist government responsible for maintaining racial inequality and discriminating against the black majority.

5. Canaan Banana (1936 - 2003)

With an HPI of 64.59, Canaan Banana is the 5th most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 45 different languages.

Canaan Sodindo Banana (5 March 1936 – 10 November 2003) was a Zimbabwean Methodist minister, theologian, and politician who served as the first President of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987. He was Zimbabwe's first head of state, a ceremonial president, after the Lancaster House Agreement that led to the country's independence. In 1987, he stepped down as president and was succeeded by Prime Minister Robert Mugabe, who became the country's executive president. In 1997, Banana was accused of being a homosexual, and after a highly publicised trial, was convicted of 11 counts of sodomy and "unnatural acts", serving six months in prison. Banana was born in Essexvale (today Esigodini), a village in Matabeleland, Southern Rhodesia, to an Ndebele mother and a Mosotho father. He was educated at a mission school before studying at Epworth Theological College in Salisbury (now Harare). Ordained in 1962, he worked as a Methodist minister and a school administrator between 1963 and 1966. He was elected Chairman of the Bulawayo Council of Churches in 1969, holding that position until 1971. From 1971 to 1973, he worked for the All Africa Conference of Churches and was also a member of the Advisory Committee of the World Council of Churches. He became involved in anti-colonial politics, embracing black liberation theology and criticising the Rhodesian government under Ian Smith, which had declared the country independent under white-minority rule in 1965. He became vice-president of the African National Congress, but soon was forced to flee Rhodesia. He first went to Japan, before moving to Washington, D.C., United States, where he studied at Wesley Theological Seminary. Upon returning to Rhodesia in 1975, he was imprisoned until 1976. That year, he accompanied Mugabe to the Geneva Conference, and in 1979, he attended the Lancaster House Conference in London that resulted in Zimbabwe's independence as a majority-rule democracy. In 1980, he became the country's first president, stepping down in 1987 so that Mugabe, who reformed the presidency from a ceremonial office into an executive one, could succeed him. Banana then worked as an Organisation of African Unity diplomat and also taught at the University of Zimbabwe. He also played a major role in arranging the union of the two main Zimbabwean revolutionary groups turned political parties, the ZAPU and his own ZANU, which merged in 1988 to form ZANU–PF, which is still the country's ruling party. In 1997, Banana was arrested in Zimbabwe on charges of sodomy, following accusations made during the murder trial of his former bodyguard, who had killed another officer who had taunted him about being "Banana's homosexual wife". The charges related to allegations that Banana had misused his power while he was president to coerce numerous men into accepting sexual advances. Though he denied the accusations, he was found guilty of eleven charges of sodomy, attempted sodomy and indecent assault in 1998. He served six months in prison, and was also defrocked. He died of cancer in 2003, with sources varying on his place of death. Banana was a controversial figure, especially after his criminal conviction. As president, he did not always command respect (a law was passed in 1982, banning Zimbabweans from joking about his surname). Nevertheless, he was held in esteem by some for his involvement in Zimbabwe's liberation struggle and later for his role in uniting ZANU and ZAPU, which ended the Gukurahundi massacres. After his death, Mugabe called him a "rare gift to the nation."

6. Morgan Tsvangirai (1952 - 2018)

With an HPI of 60.71, Morgan Tsvangirai is the 6th most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 56 different languages.

Morgan Richard Tsvangirai (; Shona pronunciation: [ts͎a.ᵑɡi.ra.i]; 10 March 1952 – 14 February 2018) was a Zimbabwean politician who was Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 2009 to 2013. He was president of the Movement for Democratic Change, and later the Movement for Democratic Change – Tsvangirai (MDC–T), and a key figure in the opposition to then-president Robert Mugabe. Tsvangirai was the MDC candidate in the controversial 2002 Zimbabwean presidential election, losing to Mugabe. He later contested the first round of the 2008 Zimbabwean presidential election as the MDC-T candidate, taking 47.8% of the vote according to official results, placing him ahead of Mugabe, who received 43.2%. Tsvangirai claimed to have won a majority and said that the results could have been altered in the month between the election and the reporting of official results. Tsvangirai initially planned to run in the second round against Mugabe, but withdrew shortly before it was held, arguing that the election would not be free and fair due to widespread violence and intimidation by government supporters that led to the deaths of 200 people. Tsvangirai sustained non-life-threatening injuries in a car crash on 6 March 2009 when heading towards his rural home in Buhera. His first wife, Susan Tsvangirai, was killed in the head-on collision. As the 2017 Zimbabwean coup d'état occurred, Tsvangirai asked Mugabe to step down. He hoped that an all-inclusive stakeholders' meeting to chart the country's future and an internationally supervised process for the forthcoming elections would create a process that would take the country towards a legitimate regime. On 14 February 2018, Tsvangirai died at the age of 65 after reportedly suffering from colorectal cancer.

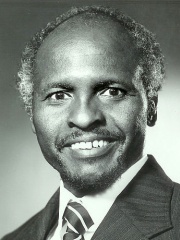

7. Rupiah Banda (1937 - 2022)

With an HPI of 60.52, Rupiah Banda is the 7th most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 46 different languages.

Rupiah Bwezani Banda (19 February 1937 – 11 March 2022) was a Zambian politician who served as the fourth president of Zambia from 2008 to 2011, taking over from Levy Mwanawasa. Banda was an active participant in politics from early in the presidency of Kenneth Kaunda, during which time he held several diplomatic posts. In October 2006, he was appointed the vice-president by Mwanawasa. After Mwanawasa suffered a stroke in June 2008 and died later that year, he became acting president. During the 2008 elections, he narrowly won against opposition leader Michael Sata of the Patriotic Front. He was later defeated in the 2011 election and succeeded by Sata.

8. Joshua Nkomo (1917 - 1999)

With an HPI of 58.48, Joshua Nkomo is the 8th most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 31 different languages.

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and Socialist politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) from 1961 until, after an internal military crackdown (known as Gukurahundi) in western Zimbabwe, mostly targeting ethnic Ndebele ZAPU supporters, ZAPU merged in 1987 with Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) to form ZANU–PF. He was a leading trade union leader, who progressed on to become president of the banned National Democratic Party, and was jailed for ten years by Rhodesia's white minority government. After his release in 1974, ZAPU contributed to the fall of that government, along with the splinter rival ZANU, created in 1963. In 1983, fearing for his life in the early stages of the Gukurahundi, Nkomo fled the country. Later in 1987, he controversially signed the Unity Accord allowing ZAPU to merge with ZANU to stop the genocide. Nkomo earned many nicknames, including Umafukufuku in Ndebele, "Father Zimbabwe" in English, and Chibwechitedza ("the slippery rock") in Shona.

9. Abel Muzorewa (1925 - 2010)

With an HPI of 56.46, Abel Muzorewa is the 9th most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 22 different languages.

Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa (14 April 1925 – 8 April 2010), also commonly referred to as Bishop Muzorewa, was a Zimbabwean bishop and politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia from the Internal Settlement to the Lancaster House Agreement in 1979. A United Methodist Church bishop and nationalist leader, he held office for less than a year.

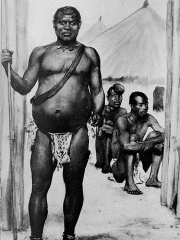

10. Lobengula (1845 - 1894)

With an HPI of 54.49, Lobengula is the 10th most famous Zimbabwean Politician. His biography has been translated into 20 different languages.

Lobengula Khumalo (c. 1835 – c. 1894) was the second and last official king of Mthwakazi (historically called Matabeleland in English). Both names in the Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields", a reference to the Ndebele warriors' use of the Nguni shield.

People

Pantheon has 13 people classified as Zimbabwean politicians born between 1845 and 1960. Of these 13, 1 (7.69%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Zimbabwean politicians include Emmerson Mnangagwa. The most famous deceased Zimbabwean politicians include Albert Lutuli, Robert Mugabe, and Ian Smith.

Living Zimbabwean Politicians

Go to all RankingsDeceased Zimbabwean Politicians

Go to all RankingsAlbert Lutuli

1898 - 1967

HPI: 77.77

Robert Mugabe

1924 - 2019

HPI: 76.85

Ian Smith

1919 - 2007

HPI: 66.29

Canaan Banana

1936 - 2003

HPI: 64.59

Morgan Tsvangirai

1952 - 2018

HPI: 60.71

Rupiah Banda

1937 - 2022

HPI: 60.52

Joshua Nkomo

1917 - 1999

HPI: 58.48

Abel Muzorewa

1925 - 2010

HPI: 56.46

Lobengula

1845 - 1894

HPI: 54.49

Phelekezela Mphoko

1940 - 2024

HPI: 54.47

Roy Welensky

1907 - 1991

HPI: 49.54

Sibusiso Moyo

1960 - 2021

HPI: 49.39

Overlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 12 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.