The Most Famous

POLITICIANS from Guatemala

This page contains a list of the greatest Guatemalan Politicians. The pantheon dataset contains 19,576 Politicians, 32 of which were born in Guatemala. This makes Guatemala the birth place of the 87th most number of Politicians behind Uzbekistan, and Somalia.

Top 10

The following people are considered by Pantheon to be the top 10 most legendary Guatemalan Politicians of all time. This list of famous Guatemalan Politicians is sorted by HPI (Historical Popularity Index), a metric that aggregates information on a biography's online popularity. Visit the rankings page to view the entire list of Guatemalan Politicians.

1. Jacobo Árbenz (1913 - 1971)

With an HPI of 70.78, Jacobo Árbenz is the most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 50 different languages on wikipedia.

Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (Spanish: [xwaŋ xaˈkoβo ˈaɾβens ɣusˈman]; 14 September 1913 – 27 January 1971) was a Guatemalan military officer and politician who served as the 25th president of Guatemala. He was Minister of National Defense from 1944 to 1950, before he became the second democratically elected President of Guatemala, from 1951 to 1954. He was a major figure in the ten-year Guatemalan Revolution, which represented some of the few years of representative democracy in Guatemalan history. The landmark program of agrarian reform Árbenz enacted as president was very influential across Latin America. Árbenz was born in 1913 to a wealthy family, son of a Swiss German father and a Guatemalan mother. He graduated with high honors from a military academy in 1935, and served in the army until 1944, quickly rising through the ranks. During this period, he witnessed the violent repression of agrarian laborers by the United States-backed dictator Jorge Ubico, and was personally required to escort chain-gangs of prisoners, an experience that contributed to his progressive views. In 1938, he met and married María Vilanova, who was a great ideological influence on him, as was José Manuel Fortuny, a Guatemalan communist. In October 1944, several civilian groups and progressive military factions led by Árbenz and Francisco Arana rebelled against Ubico's repressive policies. In the elections that followed, Juan José Arévalo was elected president, and began a highly popular program of social reform. Árbenz was appointed Minister of Defense, and played a crucial role in putting down a military coup in 1949. After the death of Arana, Árbenz ran in the presidential elections that were held in 1950 and without significant opposition defeated Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, his nearest challenger, by a margin of over 50%. He took office on 15 March 1951, and continued the social reform policies of his predecessor. These reforms included an expanded right to vote, the ability of workers to organize, legitimizing political parties, and allowing public debate. The centerpiece of his policy was an agrarian reform law under which uncultivated portions of large land-holdings were expropriated in return for compensation and redistributed to poverty-stricken agricultural laborers. Approximately 500,000 people benefited from the decree. The majority of them were indigenous people, whose forebears had been dispossessed after the Spanish invasion. His policies ran afoul of the United Fruit Company, which lobbied the United States government to have him overthrown. The U.S. was also concerned by the presence of communists in the Guatemalan government, and Árbenz was ousted in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état engineered by the government of U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower through the U.S. Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency. Árbenz went into exile through several countries, where his family gradually fell apart, and his daughter committed suicide. He died in Mexico in 1971. In October 2011, the Guatemalan government issued an apology for Árbenz's overthrow.

2. Álvaro Colom (1951 - 2023)

With an HPI of 66.78, Álvaro Colom is the 2nd most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 41 different languages.

Álvaro Colom Caballeros (Spanish: [ˈalβaɾo koˈlon]; 15 June 1951 – 23 January 2023) was a Guatemalan engineer, businessman, and politician who served as the 47th president of Guatemala from 2008 to 2012, as well as the General-Secretary of the political party, National Unity of Hope (UNE).

3. Efraín Ríos Montt (1926 - 2018)

With an HPI of 64.87, Efraín Ríos Montt is the 3rd most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 38 different languages.

José Efraín Ríos Montt (Spanish: [efɾaˈin ˈrios ˈmont]; 16 June 1926 – 1 April 2018) was a Guatemalan military officer who served as de facto President of Guatemala from 1982 to 1983. His brief tenure as chief executive was one of the bloodiest periods in the long-running Guatemalan Civil War. Ríos Montt's counter-insurgency strategies significantly weakened the Marxist guerrillas organized under the umbrella of the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (URNG), while also leading to accusations of war crimes and acts of genocide perpetrated by the Guatemalan Army under his leadership. Ríos Montt was a career army officer. He was director of the Guatemalan military academy and rose to the rank of brigadier general. He was briefly chief of staff of the Guatemalan army in 1973. However, he was soon forced out of the position over differences with the military high command. He ran for president in the 1974 general election, losing to the official candidate, General Kjell Laugerud, in an electoral process widely regarded as fraudulent. In 1978, Ríos Montt left the Catholic Church and joined an Evangelical Christian group affiliated with the Gospel Outreach Church. In 1982, discontent with the rule of General Romeo Lucas García, the worsening security situation in Guatemala, and accusations of electoral fraud led to a coup d'état by a group of junior military officers who installed Ríos Montt as head of a government junta. Ríos Montt ruled as a military dictator for less than seventeen months before his defense minister, General Óscar Mejía Victores overthrew him in another coup. In 1989, Ríos Montt returned to the Guatemalan political scene as leader of a new political party, the Guatemalan Republican Front (FRG). He was elected many times to the Congress of Guatemala, serving as president of the Congress in 1995–96 and 2000–04. A constitutional provision prevented him from registering as a presidential candidate due to his involvement in the military coup of 1982. However, the FRG obtained the presidency and a congressional majority in the 1999 general election. Authorized by the Constitutional Court to run in the 2003 presidential elections, Ríos Montt came in third and withdrew from politics. He returned to public life in 2007 as a member of Congress, thereby gaining legal immunity from long-running lawsuits alleging war crimes committed by him and some of his ministers and counselors during their term in the presidential palace in 1982–83. His immunity ended on 14 January 2012, when his legislative term of office expired. In 2013, a court sentenced Ríos Montt to 80 years in prison for genocide and crimes against humanity, but the Constitutional Court quashed that sentence, and his retrial was not completed before he died of a heart attack in April 2018.

4. Carlos Castillo Armas (1914 - 1957)

With an HPI of 62.96, Carlos Castillo Armas is the 4th most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 29 different languages.

Carlos Castillo Armas (locally ['kaɾlos kas'tiʝo 'aɾmas]; 4 November 1914 – 26 July 1957) was a Guatemalan military officer and politician who was the 28th president of Guatemala, serving from 1954 to 1957 after taking power in a coup d'état. A member of the far-right National Liberation Movement (MLN) party, his authoritarian government was closely allied with the United States. Born to a planter, out of wedlock, Castillo Armas was educated at Guatemala's military academy. A protégé of Colonel Francisco Javier Arana, he joined Arana's forces during the 1944 uprising against President Federico Ponce Vaides. This began the Guatemalan Revolution and the introduction of representative democracy to the country. Castillo Armas joined the General Staff and became director of the military academy. Arana and Castillo Armas opposed the newly elected government of Juan José Arévalo; after Arana's failed 1949 coup, Castillo Armas went into exile in Honduras. Seeking support for another revolt, he came to the attention of the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In 1950 he launched a failed assault on Guatemala City, before escaping back to Honduras. Influenced by lobbying by the United Fruit Company and Cold War fears of communism, in 1952 the US government of President Harry Truman authorized Operation PBFortune, a plot to overthrow Arévalo's successor, President Jacobo Árbenz. Castillo Armas was to lead the coup, but the plan was abandoned before being revived in a new form by US President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953. In June 1954, Castillo Armas led 480 CIA-trained soldiers into Guatemala, backed by US-supplied aircraft. Despite initial setbacks to the rebel forces, US support for the rebels made the Guatemalan army reluctant to fight, and Árbenz resigned on 27 June. A series of military juntas briefly held power during negotiations that ended with Castillo Armas assuming the presidency on 7 July. Castillo Armas consolidated his power in an October 1954 election, in which he was the only candidate; the MLN, which he led, was the only party allowed to contest the congressional elections. Árbenz's popular agricultural reform was largely rolled back, with land confiscated from small farmers and returned to large landowners. Castillo Armas cracked down on unions and peasant organizations, arresting and killing thousands. He created a National Committee of Defense Against Communism, which investigated over 70,000 people and added 10 percent of the population to a list of suspected communists. Despite these efforts, Castillo Armas faced significant internal resistance, which was blamed on communist agitation. The government, plagued by corruption and soaring debt, became dependent on aid from the US. In 1957 Castillo Armas was assassinated by a presidential guard with leftist sympathies. He was the first of a series of authoritarian rulers in Guatemala who were close allies of the US. His reversal of the reforms of his predecessors sparked a series of leftist insurgencies in the country after his death, culminating in the Guatemalan Civil War of 1960 to 1996.

5. Jorge Ubico (1878 - 1946)

With an HPI of 62.26, Jorge Ubico is the 5th most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 27 different languages.

Jorge Ubico Castañeda (10 November 1878 – 14 June 1946), nicknamed Number Five or also Central America's Napoleon, was a Guatemalan military officer, politician, and dictator who served as the president of Guatemala from 1931 to 1944. A general in the Guatemalan military, he was elected to the presidency in 1931, in an election where he was the only candidate. He continued his predecessors' policies of giving massive concessions to the United Fruit Company and wealthy landowners, as well as supporting their harsh labor practices. Ubico has been described as "one of the most oppressive tyrants Guatemala has ever known" who compared himself to Adolf Hitler. He was removed by a pro-democracy uprising in 1944, which led to the ten-year Guatemalan Revolution.

6. Rafael Carrera (1814 - 1865)

With an HPI of 62.15, Rafael Carrera is the 6th most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 29 different languages.

José Rafael Carrera y Turcios (24 October 1814 – 14 April 1865) was the president of Guatemala from 1844 to 1848 and from 1851 until his death in 1865, after being appointed President for life in 1854. He ruled during the establishment of new Central American nations and William Walker's invasions, liberal attempts to overthrow him, Mayan uprisings in the east, the Belize boundary dispute with the United Kingdom, and conflicts in Mexico under Benito Juárez. Carrera is seen as a caudillo, a term that refers to Latin American charismatic populist leaders of military background, sometimes among indigenous people. Carrera became a dominant figure in Guatemala for three decades. He led a major revolt against the liberal government of Mariano Gálvez that marked the dissolution of Federal Republic of Central America. After the liberals came back to power in Guatemala in 1871, Carrera's character and regime were dismissed and demonized, making him look as an illiterate who could not even write his own name manipulated by the anti-liberal faction. Over the years, even Marxist writers who wanted to show how the native Guatemalans have been exploited by elites completely ignored Carrera's support of them and accused him of racism and being a "little king".

7. Juan José Arévalo (1904 - 1990)

With an HPI of 61.46, Juan José Arévalo is the 7th most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 25 different languages.

Juan José Arévalo Bermejo (10 September 1904 – 8 October 1990) was a Guatemalan statesman and professor of philosophy who became Guatemala's first democratically elected president in 1945. He was elected following a popular uprising against the United States-backed dictator Jorge Ubico that began the Guatemalan Revolution. He remained in office until 1951, surviving 25 coup attempts. He did not contest the election of 1951, instead choosing to hand over power to Jacobo Árbenz. As president, he enacted several social reform policies, including an increase in the minimum wage and a series of literacy programs. He also oversaw the drafting of a new constitution in 1945. His son, Bernardo, became President of Guatemala in 2024. Because of his reforms and policies that transcended his time, Juan José Arévalo is considered the most popular and influential president in the history of Guatemala.

8. Otto Pérez Molina (b. 1950)

With an HPI of 61.45, Otto Pérez Molina is the 8th most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 44 different languages.

Otto Fernando Pérez Molina (born December 1, 1950) is a Guatemalan politician and retired general who served as the 48th president of Guatemala from 2012 to 2015. Standing as the Patriotic Party (Partido Patriota) candidate, he lost the 2007 presidential election but prevailed in the 2011 presidential election. During the 1990s, before entering politics, he served as Director of Military Intelligence, Presidential Chief of Staff under President Ramiro de León Carpio, and as the chief representative of the military for the Guatemalan Peace Accords. On being elected President, he called for the legalization of drugs. On September 2, 2015, beset by corruption allegations and having been stripped of his immunity by Congress the day earlier, Pérez presented his resignation. He was arrested on September 3, 2015. Following his arrest, Pérez remained in prison until he was released on bond in January 2024; prior to his release, Pérez received convictions and jail sentences in 2022 and 2023.

9. Alejandro Giammattei (b. 1956)

With an HPI of 60.89, Alejandro Giammattei is the 9th most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 38 different languages.

Alejandro Eduardo Giammattei Falla (Spanish pronunciation: [aleˈxandɾo ʝamaˈtej]; born 9 March 1956) is a Guatemalan politician who was the 51st president of Guatemala from 2020 to 2024. He is a former director of the Guatemalan penitentiary system and participated in Guatemala's presidential elections in 2007, 2011, and 2015. He won in the 2019 election, and assumed office on 14 January 2020.

10. Óscar Berger (b. 1946)

With an HPI of 60.20, Óscar Berger is the 10th most famous Guatemalan Politician. His biography has been translated into 35 different languages.

Óscar José Rafael Berger Perdomo (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈoskaɾ xoˈse rafaˈel βeɾˈʃe peɾˈðomo]; born 11 August 1946) is a Guatemalan businessman and politician who served as the 46th president of Guatemala from 2004 to 2008. He previously served as mayor of Guatemala City from 1991 to 1999.

People

Pantheon has 32 people classified as Guatemalan politicians born between 1804 and 1969. Of these 32, 12 (37.50%) of them are still alive today. The most famous living Guatemalan politicians include Otto Pérez Molina, Alejandro Giammattei, and Óscar Berger. The most famous deceased Guatemalan politicians include Jacobo Árbenz, Álvaro Colom, and Efraín Ríos Montt. As of April 2024, 2 new Guatemalan politicians have been added to Pantheon including Karin Herrera, and Norma Torres.

Living Guatemalan Politicians

Go to all RankingsOtto Pérez Molina

1950 - Present

HPI: 61.45

Alejandro Giammattei

1956 - Present

HPI: 60.89

Óscar Berger

1946 - Present

HPI: 60.20

Vinicio Cerezo

1942 - Present

HPI: 57.86

Jorge Serrano Elías

1945 - Present

HPI: 57.45

Alejandro Maldonado

1936 - Present

HPI: 56.42

Alfonso Portillo

1951 - Present

HPI: 55.96

Jimmy Morales

1969 - Present

HPI: 55.25

Carlos Batres

1968 - Present

HPI: 53.96

Sandra Torres

1955 - Present

HPI: 52.42

Karin Herrera

1967 - Present

HPI: 47.00

Norma Torres

1965 - Present

HPI: 36.49

Deceased Guatemalan Politicians

Go to all RankingsJacobo Árbenz

1913 - 1971

HPI: 70.78

Álvaro Colom

1951 - 2023

HPI: 66.78

Efraín Ríos Montt

1926 - 2018

HPI: 64.87

Carlos Castillo Armas

1914 - 1957

HPI: 62.96

Jorge Ubico

1878 - 1946

HPI: 62.26

Rafael Carrera

1814 - 1865

HPI: 62.15

Juan José Arévalo

1904 - 1990

HPI: 61.46

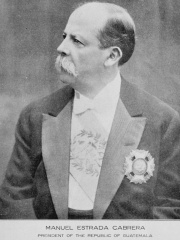

Manuel Estrada Cabrera

1857 - 1924

HPI: 59.75

Álvaro Arzú

1946 - 2018

HPI: 59.54

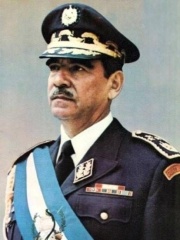

Óscar Humberto Mejía Víctores

1930 - 2016

HPI: 59.10

Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes

1895 - 1982

HPI: 59.09

Fernando Romeo Lucas García

1924 - 2006

HPI: 58.00

Newly Added Guatemalan Politicians (2025)

Go to all RankingsOverlapping Lives

Which Politicians were alive at the same time? This visualization shows the lifespans of the 20 most globally memorable Politicians since 1700.